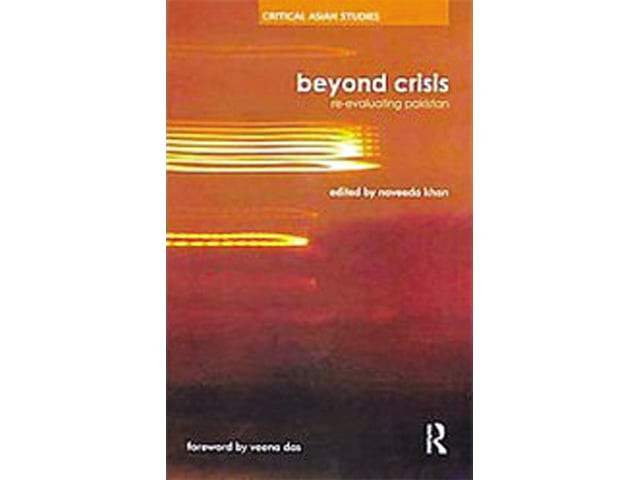

New perspectives: Reevaluating Pakistan

Beyond Crisis: Reevaluating Pakistan is both a revelation and a comfort because of its innovative perspectives.

Beyond Crisis takes us away from the usual discourse on Pakistan that focuses on the various threats endangering its very existence, and delves deep into the essence of what it means to live in Pakistan. Rationalising the problems in our society is the most common mode of cognition in Pakistan but it can be replaced by a method that focuses on studying the diversity that is found in our culture and its relation with state, law, religion and ethnicity.

This work does not aspire to present a picture of Pakistan in its totality, but rather examines different strata of society to reveal how an understanding of the bigger issues faced by Pakistan can emerge as a result of this engagement.

Divided into four parts — (i) The Artificiality of the State, (ii)

Nationalist Visions, (iii) The Foreignness Within, and (iv) The Everyday — each of which consists of four essays on the essence of what it is to be a Pakistani, Beyond Crisis is a detailed study of a number of central spheres of Pakistani society.

In the section Artificiality of the State, the problematic relation between state and citizens shows how the discomfort with the state should be seen not as “seeking separation from it but assimilation within it”. The first article, titled Towards a Lyric History of India, presents a vivid analysis of the poetry of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, the progressive Pakistani poet. Amir R Mufti shows how the legacy of partition haunts Faiz’s poetry and the predominant themes of exile and homelessness in his poetry can be seen as an exposition of the artificiality of state: “what Faiz’s love lyrics give expression to is a self in partition”.

The second section, The Difficulty of Nationalist Visions, shows how the theme of foreignness can be found in the failure of different attempts at a national vision. Registering Crisis: Ethnicity in Pakistani Cinema of the 1960s and 1970s by Iftikhar Dadi is a masterpiece of film criticism in Pakistan. According to Dadi, the decline of Urdu films is the cinematic articulation of the failure of Urdu as a national language and the absence of a single nationalist vision. In another article in this section titled Learning to be Left: Jamaat-e Islami in Pakistan, Humeira Iqtidar reinterprets the history of JI by showing how this belligerently anti-left political party’s oppositional engagement with the ‘left’ had a deep impact on its strategies, constituencies and ultimately, its stance on various issues.

The third section titled Foreignness Within presents a radical analysis of ‘internal’ foreignness instead of a traditional account of external influences on Pakistan. The fourth section takes us to everyday life in the country and by concentrating on otherwise mundane aspects suggests how power relations are embedded in social life. In the book’s final essay Mosque Construction or the Violence of the Ordinary, Naveeda Khan presents an ethnographic picture of three mosques in Lahore as places for experimenting being Muslim at both the individual and communal level. Her intellectually penetrating take on the ordinary unveils the extraordinary beneath it.

Despite the book’s academic jargon, the work is relatively clear and accessible. An engaging, informative study tracking the specificities of Pakistan’s history, politics and everyday life, it helps us ask new questions and goes beyond the prevalent nostalgic rhetoric which makes for refreshing reading, with no sense of a contingent apocalypse. The multidisciplinary nature of the work ensures that those with a taste for intellectual investigation will find it intriguing. In short, it is a valuable and inspiring addition to Pakistani scholarship.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, February 6th, 2011.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ