A smear of colour, a string of poetry, and a rebel

Ghani Khan, the fierce Pakhtun warrior of peace, waged war within the meters of his verses.

Ghani Khan, the fierce Pakhtun warrior of peace, waged war within the meters of his verses.

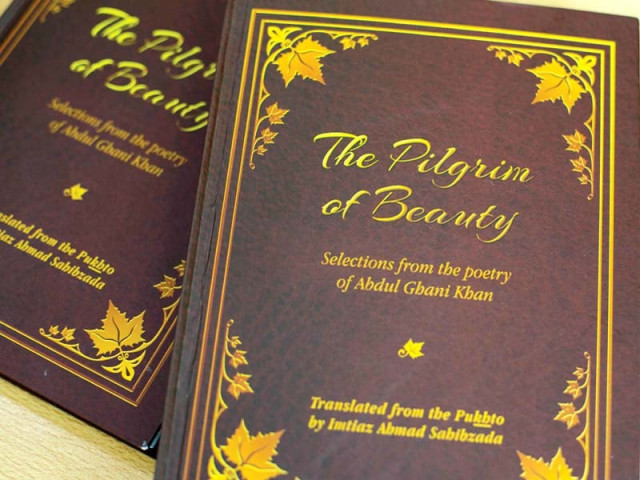

If the philosopher, painter, sculptor and poet Ghani Khan is an exponent of transcendental love, the latest offering by Imtiaz Sahibzada, Pilgrim of beauty, can be rightly described as a labour of love. The writer’s effort reflects upon an unconditional devotion that spans across an entire lifetime to render the enigmatic poet universal and translate a substantial number of his Pushto poems in English.

Recording the tumultuous life and conflicts of the Pushto thinker, Sahibzada weaves through Ghani Khan’s poetic and artistic journey from the early years during the British India, his struggle against the conformity of traditional Pakhtun society and the role of a predominant mullah, apart from the equally repressive British colonial powers. The account is succinct and accessible to the average reader.

The book mentions that the overweening presence of his iconic father, Bacha Khan (Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan) dominated the free-spirited artist who yearned to break loose from the regimented and ascetic upbringing. His poetry thus symbolises the agony and ecstasy of a passionate soul in search of nirvana — the eternal bliss.

While the young poet was studying at the University of Southern Louisiana, Ghani Khan was arrested along with other Congress leaders in 1931. As a consequence, the family ran into financial hardships. Compelled to discontinue his education, upon his return to India, he was sent to Allahabad to stay at Anand Bhawan, the residence of the Nehru family, under Jawaharlal Nehru’s watch for eight months. In February 1934, Nehru arranged for both Ghani Khan and Indira to study at Shantiniketan, the institution established by the Nobel laureate, poet-philosopher, Rabindranath Tagore.

As student of journalism, Ghani Khan also took up sculpture and painting. His sojourn in the West, and later Shantiniketan, profoundly affected him. Unfortunately for Ghani Khan, when his father Bacha Khan visited Shantiniketan, he did not approve of the liberal lifestyle, co-education as well as his son’s pre-occupation with sculpture and painting — activities he did not consider of practical value in the ongoing struggle against British rule — and decided to withdraw him in mid-course from the institution. Both Gandhi’s intercession to let him complete his studies and Tagore’s personal efforts proved futile. Bacha Khan’s response to their pleading was: “The map of the sub-continent would not change if Ghani put green, red or yellow to the canvas!” His subsequent withdrawal from Shantiniketan in October 1934 is considered a great loss to the world of Indian art.

Ghani Khan’s literary journey began with his first poem in Pukhtoon, a monthly launched by Bacha Khan in 1928 as an organ of the Khudai Khitmatgar Movement for the promotion of Pushto language, besides, social and political reform of the Pakhtuns. He would contribute to both prose and poetry to the journal and touch upon the social, political and moral issues, under the nom de plume, Lewanae Falsafi, which translates from Pushto as the mad philosopher.

The Pathans was his first book published in English in 1947 and remains a unique and authoritative history of the Pakhtuns. The 50 pages carry a sweeping historical account of the most volatile people, written with an acerbic wit and in a disarming satire and which makes for a reader’s delight.

His memorable poem, Wasiyat, was carried on the tile page of all publications of the journal. This poem is still engraved on a small monument erected on the Pakistan side of the Wagah border in Punjab. “My poetry” said Ghani Khan once, “is the about humanism, and the search for truth. It’s about self-realisation. I want to see my people educated and enlightened. A people with a vision and strong sense of justice, who can carve out a future for themselves in harmony with nature”.

In his paintings, he was inspired by the impressionists but imitated no one. One can find sparks of Monet, Manet and Van Gogh, with particular inspiration of Gaugin colours. With exclusive focus on renderings of human face, Ghani Khan’s inspirational style does not fall within the strict definition of known schools. In his words, “I consider the human face to be the most significant. A person’s thoughts, ambitions, his character, are all reflected on it. I work from memory; I have never had people modeling for me”.

Ghani Khan died on 15 March, 1996 and was buried next to his mother in his ancestral graveyard as was desired by him. His passing away closed a chapter of an eminent poet, painter, sculptor and writer, besides a leader who played a significant role during the independence movement.

The Pilgrim of Beauty by Sahibzada is a lasting tribute to Ghani Khan whose centenary is being celebrated this year. The English translation of selected Pushto poems and some reproductions of his famous paintings complement the beautifully crafted masterpiece. The voluminous introduction, index, glossary and notes are a work of meticulous research, for which the writer deserves our gratitude, and for introducing Ghani Khan’s genius to the outside world.

Published in The Express Tribune, March 15th, 2015.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ