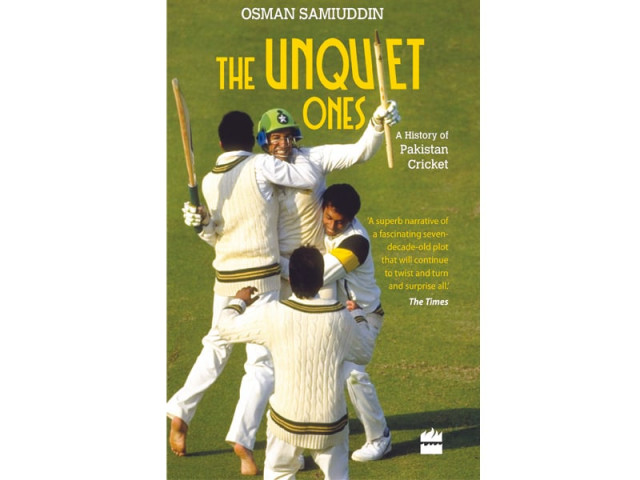

Book review: The Unquiet Ones - war and peace and reverse swing

Osman Samiuddin’s The Unquiet Ones: A History of Pakistan Cricket is a triumph

Breaking News: In a World Cup year, Pakistan cricket has already won. Osman Samiuddin’s The Unquiet Ones: A History of Pakistan Cricket is a triumph.

To grasp the extent of the feat, think of the national cricket story itself as a massive sprawling Great Pakistani Novel. War And Peace And Reverse Swing. First there is the overwhelming content. The book runs to 500 pages; one suspects Samiuddin could have filled five or six volumes with all his material.

Then consider the approach. What genre is this epic tale? Tragedy, romance, thriller, melodrama, farce? All of the above, of course, and more. Samiuddin’s monumental achievement is synthesizing all this noise and all these tones into a comprehensive and clean recounting. Pakistan cricket, the greatest story ever told but told too often by long-winded uncles, finally has the chronicler it deserves.

His voice has authority and insight. The Oval victory of ’54 figures prominently in every Pakistan fan’s consciousness, but till now only at a distance. The chapter here makes the reader a 12th man in the dressing room, observing AH Kardar and Fazal Mahmood from such close quarters one actually gets into their heads.

A great sports book must appeal to non-sports-geeks. Samiuddin is expert at conveying the bigger picture. There is a constant contextualizing of the state of the nation, its cultural life, its sense of self as country and cricket team through the ages. The early days are beautifully captured, particularly college and club cricket in Lahore after Partition, where you could have drink with a player during a game, chat about what went wrong the previous over, when “the gap between cricketer and non-cricketer was narrow.”

We get a running social commentary, all done with a light touch: a spotlight on forgotten parts, from Bangladesh to Balochistan; a wry nostalgia for a time PIA was world class and Pakistan on the up; sharp comment on Javed Miandad and social class.

Javed himself might say that cricket is a team sport of individual contests, and here the big personalities are given penetrative chapters. We are shown the complex hauteur of AH Kardar, the noble loneliness of Hanif Mohammad, the Left Arm Divinations of Wasim Akram. There is also the best man-crush writing you could hope to find on Fazal – for a study of Pakistan cricket is inevitably an inquiry into Pakistani masculinity.

Indeed, mention is made of Fazal’s long toned biceps and how he had immense stamina, once bowling 45 overs in a Test match day. These two observations might serve as an image for the book. Each page has a taut muscularity, but it keeps its pace over the long haul. You even sense, at times, that Samiddin has reigned in the flourishes we’re used to from his work in The National, ESPN Cricinfo and elsewhere, aware that a flashy cover drive every ball won’t result in a long innings. That the book never falls back on these sorts of lazy cricket metaphors is another testament to its achievement.

Still, almost every page has verbal delights. On Imran Khan’s early bowling action: “… more windmills in it than Holland, and just as flat”; his later perfection is “a leaping study in the beauty and grace of the human form.” There are marvellous anecdotes. One transports us to a rollicking Indian train carriage, huddled together with journalists and beers, listening to Chetan Sharma talking about that ball.

There is an impressive precision. In little over a page, we get a full historical overview of Minto Park, now Iqbal Park. Characters from Pir Pagara to President Eisenhower make memorable cameos. The chapter on match-fixing is a masterpiece of clarity, telling a labyrinthine story, real snake-eating-its-own-tail-stuff, so well that one finally forms a clear picture of this unfortunate mess. The only thing which comes out clean is the pristine writing.

The research – let us call it scholarship – is immense. If there is something essential about Pakistani cricket, you feel it is here. One doesn’t know when Samiuddin first embarked on the book, though it probably formed in his mind at the first instant he matched his love of cricket with the pursuit of writing. He mentions that an interview with Nur Khan for the book was conducted in 2008, so we know it’s been at least seven years in the making. But there’s a lifetime’s passion and learning on display. Dusty newspaper clippings merge seamlessly with memories perhaps formed as a child watching televised games from Sharjah. Samiuddin has been a constant name for over a decade in online cricket writing, and the book has lovely pieces on radio and TV commentary. The Unquiet Ones cements his place as the Omar Kureishi / Jamshed Marker for our times.

This being Pakistan cricket, humour runs through the spine of the story. There’s a particularly well-drawn scene of a 2009 Senate hearing, Ijaz Butt and Javed the squabbling aunties within a comical soap opera. The fun intertwines with sadness, though, from deeply tragic endings to the many little cruelties that even current players, such as Younis and Misbah, have had to undergo through our non-system. A recent book on Karachi spoke of “ordered disorder” and this might also serve as the through-line for The Unquiet Ones.

However, there has been some administrative success, covered meticulously here. The author superbly charts the transformation from the relatively dour 60s to 80s superstar glitz. One also enjoys his precise accounting, giving all the main monetary figures for contracts, TV deals, sponsorship and so on.

There is one inaccuracy. “Safdar Minhas was a tall, fast off-cutter…”, writes Samiuddin, but the use of the past tense is wrong. Minhas, a former Eaglet now in his 80s, still sends them down from a great height and with zip to his grandchildren. I only know this because he is my father-in-law. These same grandchildren showed me a Youtube clip of some Shahid Afridi blitz the other day. I spotted a Waqar Younis Yorkers complication on the sidebar. They were impressed, but had no idea of the origins of reverse swing, no knowledge of those multifaceted battles, on and off the pitch. This book ensures our grandchildren and those after them will know the full story of Pakistan cricket.

The Unquiet Ones ends with a chapter on fast bowling, taking in tape ball cricket and a final passage on Mohammad Amir. There is a melancholy glow – “fast bowling and corruption: the richness of Pakistan in one, its poverty in the other” – which somehow fills the heart with hope. After all, as Samiuddin writes, “Pakistan appears to live fullest when imagining its own imminent death.” And it is life in its fullest shape which permeates this book.

Later this year Amir returns from a five-year ban. Who knows what the future holds in store, for him and the team. We hope the future of Pakistan cricket is smoother than its history. (But when it’s this interesting, do we really?) Whatever happens, one already looks forward to the author’s new editions and updates of this great book.

Imran Yusuf is a writer.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, January 11th, 2015.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ