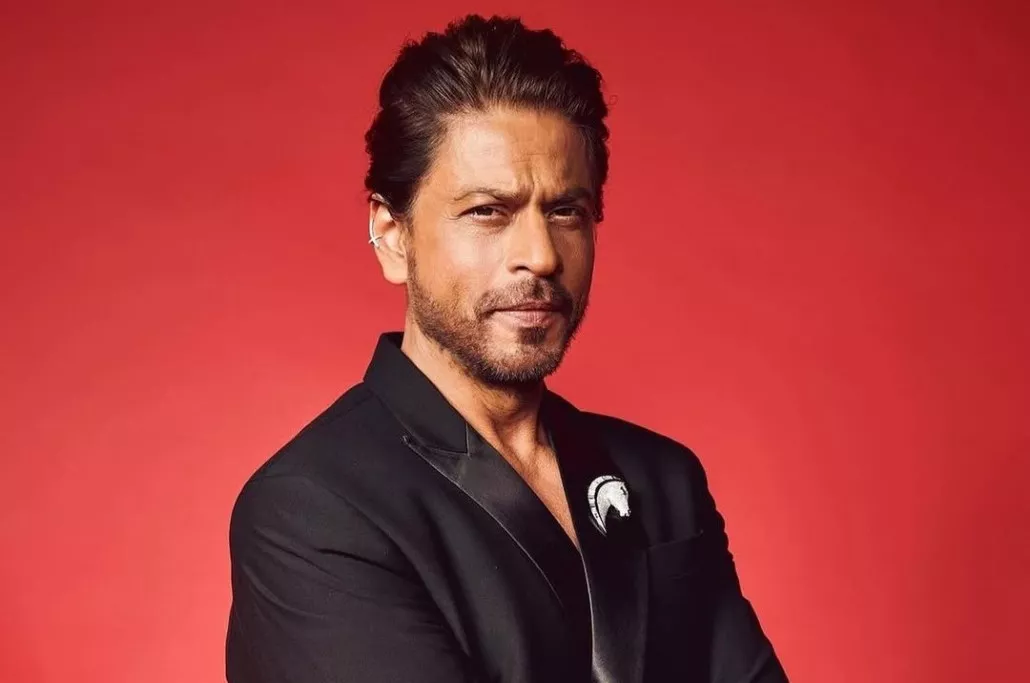

2024: The year SRK became a feminist sweetheart and no one knows why

After a blockbuster comeback in 2023, it has become woke to love King Khan despite his complicated legacy

KARACHI:In one of the most iconic scenes from Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), Shah Rukh Khan teeters on the edge of every woman’s worst nightmare. His character, Raj, finds himself locked in a train compartment with Simran (Kajol). Simran is reserved, traditional, and decidedly uninterested in the charming yet invasive stranger determined to disrupt her solitude.

She doesn’t lash out immediately. When Raj awkwardly jokes, “There’s no one at home,” after knocking futilely on the compartment door, Simran offers a polite smile and turns her attention back to her book. But Raj, like so many men before him, doesn’t misread the signals—he blatantly ignores them. What follows is an escalating series of humiliations: Raj flaunts her lingerie with a smirk, croons “Tum mein, ek dabbe mein band hon,” slides on his sunglasses, and cosies up beside her. When Simran firmly says, “Please leave me alone,” Raj doesn’t just dismiss her resistance; he mocks it, resting his head brazenly on her lap.

If Simran had been asked whether she’d rather share that compartment with a man or a bear, the answer would’ve been obvious. Yet, DDLJ endures as a timeless love story—a cornerstone of Bollywood’s romantic canon.

It also serves as the prototype for Shah Rukh’s signature brand of on-screen masculinity: one that smooths over boundary-pushing behavior with irresistible charm, blurring lines between flirtation and coercion. This archetype, rooted in an aestheticised working-class, old-school romance, isn’t just central to Shah Rukh’s persona—it has informed and sustained Bollywood’s storytelling for decades, proving both durable and lucrative. And it is precisely one that has enabled a viewing public that delights in the violence of films such as Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s Animal (2023).

A strange legacy

2023 marked Shah Rukh’s roaring comeback, a year that saw him dominate box offices with Pathaan and Jawan, cementing his position as Bollywood’s reigning superstar. His return wasn’t just cinematic; it was cultural, sparking renewed adoration from fans and a frenzy of discourse around his legacy.

In 2024, Shah Rukh redefined what cinematic stardom could mean — and demand — in a globalised, hyper-connected era of Indian cinema. At the 24th International Indian Film Academy (IIFA) Awards, his performance in Jawan earned him the Best Actor award. Later in the year, under the starry skies of Switzerland, he became the first Indian artist to receive the Pardo alla Carriera Ascona-Locarno Tourism award at the 77th Locarno Film Festival. Meanwhile, the internet anointed him as a feminist sweetheart, a title buoyed by his comments on gender equality and carefully curated gestures of respect for women.

Two years before DDLJ, Shah Rukh was a new and promising villain. His portrayal of Rahul Mehra in Darr (1993) was sinister and obsessive, defined by the chilling refrain, “Tu haan kar ya na kar, tu hai meri Kiran.” In both Darr and Baazigar, Shah Rukh embodied a menacing intensity, earning acclaim as a popular antihero. But these films barely hinted at the softer, insistent romantic persona that would later crown him as King Khan.

The Shah Rukh Khan adored by women didn’t always come with rippling six-packs, veiny biceps, or shirtless displays under waterfalls. Instead, Shah Rukh’s charm has always been rooted in his boyish charisma and razor-sharp wit. As an actor, his performances are solid, though often eclipsed by his larger-than-life stardom. He is, and has always been, the nation’s undefeated sweetheart. And make no mistake—he adores women.

Off-screen, Shah Rukh isn’t far removed from his on-screen persona. Sure, he will not be losing his shirt to reveal a sculpted chest — that is still Salman Khan’s expertise — but he reveres women. Call it SRK feminism. “How have you bewitched women all over the world?” a woman asked him at a public event. “I have lots of free time. Every time I see a girl, I go there…,” Shah Rukh quips with a laugh before adding in a serious tone, “For women, love means respect, and I respect every woman. That's why they love me so much.”

On International Women’s Day in 2016, Shah Rukh reflected on the sacrifices and strength of women, tweeting, “Often I wish I was a woman… Then I realise I don’t have enough guts, talent, sense of sacrifice, selfless love, or beauty to be one. Thank you, girls.”

Two years later, at the World Economic Forum, he declared, “I don’t spend time in the company of men.” At a time when India—and the world—seems to be hurtling into deeper divisions and animosity, Shah Rukh stands out as a figure women find themselves reconciling with evolving feminism. Few sights are as hopeful as a Bollywood superstar unapologetically advocating for women to be loved the way they want to be.

Finding an escape

There was a time when Shah Rukh Khan was subject to uncritical adoration. Loving him, enjoying Bollywood, or even supporting artists deemed “problematic” post-cancellation was relegated to the realm of guilty pleasures. In the immediate aftermath of #MeToo, the pressure was palpable: to curate a catalogue of offences, however minor or major, and to refrain from indulgence—at least without first issuing a disclaimer of disapproval.

Years after #MeToo, that pressure has metamorphosed into personal manifestos that must account for all that is consumed. It may not be enough to love Shah Rukh and not know what his legacy means for women.

“These women relied on Shah Rukh when they found the real world and all its pandemics and practicalities inhospitable. Because only the deepest dissatisfaction with reality drives us to dwell in fantasy,” writes author Shrayana Bhattacharya in her well-received book, Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh. For those unfamiliar with this fascinating enterprise, the subtitle teases context: India's Lonely Young Women and the Search for Intimacy and Independence.

Bhattacharya links loneliness, intimacy, and visual cultures, with Shah Rukh as the bearer of desire and resistance. Her work grounds itself in interviews and testimonies, presenting women as active participants in constructing their own meanings of the Bollywood star—consumer, fan, and interpreter rolled into one. In many ways, it is merely putting into words what many have experienced for years.

This ongoing analysis of where Shah Rukh’s romanticised masculinity fits within feminist discourse wasn’t always at the forefront. Fandoms have always been spaces of politics and feeling. A hypersurveillance of your own fangirling, on the other hand, is fairly new. Bhattacharya’s scholarly engagement reflects this shift, but her concerns resonate far beyond academia. They echo the desires of countless fans who seek to rescue their favourites from the backhanded insult of a guilty pleasure.

As it happens, it takes either selective amnesia or being born into a later generation to forget the swirling rumours of his alleged affair with Priyanka Chopra or how his on-screen avatars inspired countless men to chase women who had clearly said no. Shah Rukh was always loved but not always praised.

The bad guy

What fantasy does Shah Rukh Khan truly offer? From Dil To Pagal Hai (1997) to Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham… (2001), he reimagines himself as the same wide-eyed, love-struck romantic who thrives on the thrill of unreciprocated affection. But to indulge in this fantasy requires seeing yourself as Madhuri Dixit or Kajol—never as Karisma Kapoor or Rani Mukerji, whose hearts are conveniently dismissed in the grand narrative of his romantic pursuits.

In a 2017 BuzzFeed piece, Sonia Mariam Thomas laments the experience of watching Shah Rukh through the lens of a South Indian woman, pointing to a stereotypical love for curds in Ra.One, the "loud North Indian man encountering all manner of ridiculously over-the-top South Indian cliches" in Chennai Express, and the blatant slut-shaming of Anushka Sharma's character in Jab Harry Met Sejal, disguised as well-meaning.

Shah Rukh isn’t being asked to apologise for choosing his characters, but to truly assess his legacy, one must contend with the uncomfortable parallels raised by Sandeep Reddy Vanga, who once defended his controversial filmography. “I want to tell that woman to go and ask Aamir Khan about the song Khambe Jaisi Khadi Hai—what was that? He almost attempts rape, makes her feel like she’s in the wrong, and they fall in love after that. What was all that? I don’t understand why they attack like that before checking the surroundings,” Vanga argued. While he is referencing Aamir's 1990 film Dil, is Shah Rukh’s oeuvre not guilty of encouraging similar tropes?

okay little off topic but yk the difference between the old toxic roles srk played and what rk played in animal? srk wanted his audience to hate that character and rk wanted them to hail his https://t.co/EKOxQEwfAB

— lana (@sugardaadi) December 25, 2024

Multiple posts online insist that those films are all different because “bad actions” were punished, not glamourised. In what appears a dig at Vanga, earlier in 2024 Shah Rukh remarked, “If I play a bad guy, I make sure he suffers a lot, he dies a dog's death.” But he faces no consequences for making Kajol’s character deeply uncomfortable, for leading her to believe they had sex while she was inebriated. Raj is not framed as the villain—not by Shah Rukh, not by the film.

the diff is that those toxic roles srk played were generally the villain of the story, who eventually lost in the ending but rk's role is hailed as a hero not just by the fans but in the movie itself

— Umm okayyy?? (@whorehubhai) December 26, 2024

For audiences, his charm overpowers his transgressions. For Shah Rukh, Raj is not the bad guy at all. If anything, the true villain of Vanga’s Animal, with his armoured, three-wheeled vehicle bristling with machine guns, is far less of a threat than the man locked in a train compartment with a woman, spinning his own version of romance and control. The former is one man's patriarchal fantasy while the other is an everyday scenario capable of very real harm.

Presumably safe

In a viral debate that swept TikTok not long ago, users posed a peculiar question to women: Would you rather be trapped in the woods with a man or a bear? Many, to no one’s surprise, chose the bear. But what if that hypothetical man wasn’t just any man, but a famous celebrity? Say, Timothée Chalamet, effortlessly cool in a blue hoodie and grey cargo pants. Jimin from BTS, exuding his soft-spoken charm. Or perhaps Shah Rukh himself.

The "man or bear" debate underscored a very real and grim fear of gender-based violence. The hypothetical man isn’t a known entity—a stranger, capable of anything simply because he’s unfamiliar. But does familiarity, even superficial, really change the equation? Would the answer be different if the man were a friendly grocer who’s bagged your vegetables for months or a colleague from work? Many women would still pick the bear. Something about celebrities, however, allows fans to assume a strange intimacy with them.

The internet is currently inundated by reels dissecting Blake Lively’s allegations against Justin Baldoni. Defenders of Baldoni, wary of appearing dismissive of women, preface their scepticism with qualifiers like, "I’m a feminist, but…" or "I support women, but…" Be it fans or bystanders, the internet excels at generating intimacies. Baldoni, who played Rafael Solano on Jane the Virgin for five years and often champions women’s rights publicly, feels familiar. Familiar enough that for some, the allegations don’t square with the man they think they know.

Those who are team Lively will dig up and put together corresponding evidence of Baldoni’s transgressions. This is the way the internet fares.

On the same social media feeds, depending on you and your algorithm’s loyalties, Shah Rukh may appear as a feminist sweetheart. Or he may be seen opposite Anushka Sharma, candidly telling her that the first thing he notices about women is their “butt”. This is a joke, he clarifies. In an interview with Preity Zinta, he asks her if she is pregnant and decides to counter her silence with another joke. “I can make you pregnant,” he tells her.

He has one for Lady Gaga, too. In a strange, brief clip where the two share a couch before an audience, he says, “When you went out shopping, I believe you did not have enough money to buy things. So I am going to give you my watch.” Then he proceeds to get real close to Lady Gaga while she protests, “No, I don’t want it. Give it to a fan.” This, too, is a joke for he is a very funny man.

The year may have belonged to Shah Rukh, a veteran star basking in the afterglow of a monumental 2023. But as the spotlight shifts, his legacy begins to cast a shadow—one that is more subtle, more insidious. It’s a brand of misogyny that isn’t borne from brute force, but from charm, from the easy charisma of a man who makes you forget, for a moment, to question the narrative he’s selling. Perhaps what fans can leave behind in 2024 is the naive expectation that someone they love—who happens to be famous—should embody a politics of progress. The power of the star, in the end, maybe its ability to make us look the other way.

Have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ