Isabel Allende: Race and freedom

Although the black-white dichotomy has lost its biological credibility, it is a lived experience within history.

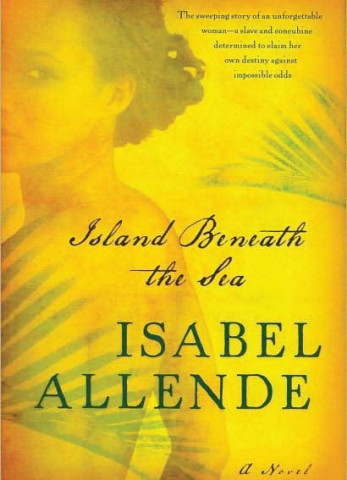

The classification of races was a simultaneous juncture with the emergence of countries and empires in what Foucault calls the ‘Classical Episteme.’ These Western fetishes, classification and marginalisation remain the backdrop of Isabel Allende’s latest novel Island Beneath the Sea. Set in the French colony of Saint-Dominigue and the Vieux Carré of New Orleans, between 1770 and 1810, the story focuses on Zarité, a slave girl of mixed race who is bought by Toulouse Valmorain when she is still a frail child. Valmorain is a young Frenchman man who inherits a huge plantation and hundreds of slaves in Saint-Dominigue by his father. Zarite is condemned to a complicated relationship with her master in her search for freedom.

Although the Haitian revolt is not the focus of the narrative, Allende draws an accurate picture of the struggles between the affranchise, African slaves, the Republican and monarchist colonists. “History repeats itself, nothing changes on this damned island,” says Allende to highlight the endurance of political unrest in Haiti today. The narration of the events in the history coincides with the convergence of Zarité from a frail child who needs nourishment and protection to a strong-willed woman who projects an esoteric status beyond the apparent circumstances she inhabits.

The invocation of indigenous resources by the author gives the otherwise boring narrative its shine. This brings us to an important motif which is essential to the overall narrative. Voodoo beliefs and dances serve as merging reality and spirituality in the story. “The slave who dances is free”, Zarité is told when she is still a child. The island beneath the sea is the symbol of everlasting spiritual freedom that is the greatest desire of Zarité.

In contrast to the vibrant character of Zarité, Valmorain’s is a rather flat character—a self-centered chauvinistic authoritative man. Although he owns her, he does not really know his slave. By marginalizing her as the ‘Other,’ he fails to grasp the spiritual significance of Zarité.

Allende’s concept of freedom does not fit the structuralist notion of binary opposition of a slave master: Valmorain is a slave to his limited vision, his wife cannot escape her own mental terrors, while Zarité is capable of experiencing the essence of freedom in her dance: “No one can harm me when I am with the drums, I become as overpowering as Erzulie, loa of love”. Allende’s ambivalent treatment of freedom is closer to the post-structuralist emphasis on textual aporia we find in Derrida and Bhabha.

Enlightening and entertaining at the same time, Island Beneath the Sea is a great addition to Latin-American literature.

Published in The Express Tribune, October 17th, 2010.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ