In the shade of a Peopaal tree, Sunyali and her children are silhouetted against the blue Nepal skies. The scene is idyllic but the family’s anxiety undercuts it: crop yields have fallen drastically this year.

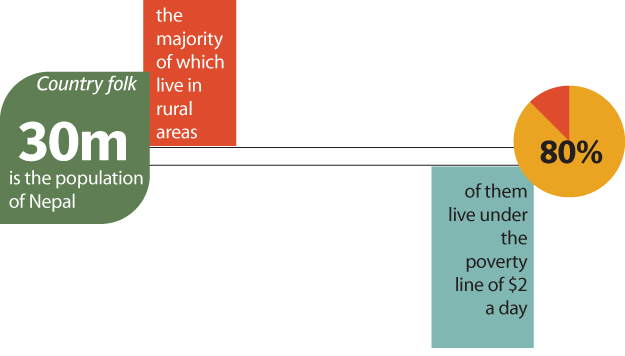

“Over the last decade or so, rainfall has become increasingly unpredictable,” she explains, estimating a 40 per cent drop in what the earth produced. The vagaries of Nature were to blame. “When the crops needed water, it did not rain… and then suddenly it rained cats and dogs.” This erratic behaviour slowly eroded farmer confidence. Like Sunyali, a vast majority of Nepali women making a living from the land in the landlocked country of 30 million people.

Deforestation in a Nepali village. PHOTO: SHABBIR MIR

Over the last few years, Nepal has been seeing more and more extreme temperatures as weather patterns have grown unpredictable. Winters are drier and summer monsoons more delayed. For years, the farmers have lived in harmony with nature in the mountainous villages. And while they may not have necessarily contributed much to climate change, they are certainly feeling its effects now.

Sunyali and the other villagers in the area once used to grow rice but in recent years they have switched to cash crops such as potato, cauliflower, cabbage, maize and beans. While incomes have improved, there are now worried that changes in the climate will lead to lower crop yields and their livelihoods will be threatened.

Sunyali’s husband Sate Majhi says that there is no other work to do besides growing crops.

“Due to the changes in the weather and lesser and lesser water at certain times of the year, it seems as if we won’t be able to grow anything besides maize,” he says, pointing to a field made barren since the nearby water channel dried up.

The climate change translates into lower earnings for the family that only produces eight sacks of rice a year. Their 18-year-old son, a dropout, doesn’t contribute to the household and has thus become another mouth to feed. In his defence, he does try to fish weekly.

A reflection of bystanders on a bridge is seen as they watch a Nepalese driver and a passenger are helped to push their jeep out of flood water on a road near Bagmati River in Kathmandu in 2011. PHOTO: AFP

With farming becoming less reliable, the villagers are now looking at other ways of earning money. Some make moonshine and sell it in the nearby market. Others, mainly the young men, move to Kathmandu in search of work. Many go in search of jobs overseas.

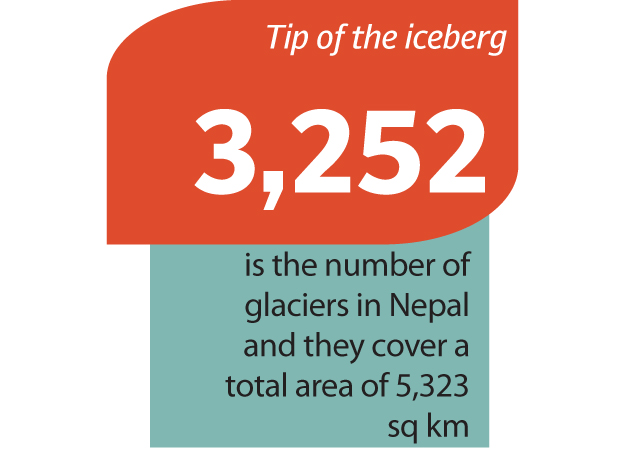

Scientists say that rainfall patterns are changing as global industrialisation pumps more and more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, preventing heat from escaping and thereby raising temperatures. While the changes are more evident in the Himalayan region than in most other areas of the planet, they could soon be felt well beyond Nepal’s borders.

PHOTO: SHABBIR MIR

“There is no doubt there’s been a change in rainfall patterns in Nepal over the past 30 years or so,” says Dr Bed Mani of the department of Environmental Sciences at Kathmandu University. “The volume of precipitation in a year is the same but the duration of such events has changed,” he explains. “It now rains at lesser intervals but with more intensity.” Farming in Nepal largely relies on monsoon rainfall because the irrigation system covers only a small area of the country.

Inconsistent rainfall and changes in climate are having an impact not just in Nepal but throughout the Himalayan region. Similar events are already taking place in Pakistan. Professor Ahmed Nafees at Karakoram International University says that the mountainous regions are more likely to be affected by the growing intensity in rainfall as this often triggers landslides and avalanches.

“Deforestation is a constant problem in the mountainous regions and when there is a heavy downpour there is nothing to hold the soil,” says Nafees. “It results in death and destruction.”

Northern Gilgit-Baltistan shares the story of Nepal’s mountains. The Pakistani villagers may not, however, at least for now, seem interested in debating the technicalities of the melting glaciers in the high Himalayas but they know that something strange is happening with the weather. “The winter rains are less frequent but they have become increasingly violent,” says Tufail Ahmad, a farmer in Gilgit. “Dry spells have become longer and the risks of landslides have increased as fierce rains have become frequent.”

Deforestation in a Nepali village. PHOTO: SHABBIR MIR

On February 6, 2013, a sudden but heavy downpour hit parts of Pakistan, India, China and Nepal. At least 45 people were killed in Pakistan alone as landslides triggered by the rains struck houses, orchards and fields in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas. In an attempt to mitigate damage and study the phenomenon, the Kathmandu-based international centre for integrated mountain development is seeking to help farmers, particularly those living in mountainous areas. The centre is implementing the Himalayan Climate Change Adaptation Programme which aims to link climate science research knowledge with the experience of farmers and communities who are already facing the consequences of climate change. “It helps them share their direct experiences of dealing with the consequences of climate change,” says Nand Kishor Agrawal, a programme coordinator at the centre’s office, “and also understand the science behind the changes that they are seeing.”

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, April 7th, 2013.

Like Express Tribune Magazine on Facebook to stay informed and join the conversation.

COMMENTS (2)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ

1730752226-0/Untitled-design-(35)1730752226-0-165x106.webp)

1730706072-0/Copy-of-Untitled-(2)1730706072-0-270x192.webp)

This is a good account of the flight of climate change refugees of the future in mountain areas, with high accumulation of glaciers and vertical deserts.

While the villagers in Nepal and in Gilgit Baltistan may be aware of the changes happening around, the severity and increased frequency of climate change related hazards and disaster events, the national media, the government policy makers and the academia and development and DRR agencies need to work togther under one framework to develop capacities of local authorities and communities in responding to and reducing risks.

There is a geniune need for collaborations, public-private partnerships and creating a functional link between research, policy and practice on ground to getting prepared for this challenge. The businesses, governments and people in the plains of Pakistan need to understand that their life styles and food production is dependent on the water flows from the mountains, and they need to pay for the environmental services, to keep promote sustainable livelihoods in mountain regions.

So what else is new? Its the same story everywhere .Things degenerate with time.