Up north and personal: Winds of change

With winter around the corner, nomads and refugee tribes are on the move.

Up north and personal: Winds of change

The sharp smell and waking sounds of ponies is the first indication of a Gujjar nomad camp at their traditional, biannual, camping ground on the other side of my home mountain. Their usual trekking route from summer grazing grounds in Azad Kashmir down to wintering places in the plains of Punjab is through the main Kashmir Highway, which is not far from here. They are making their downward trek early this year, which makes me wonder what they have deduced about the winter to come. It is usually the beginning of October before they pass through here.

A welcoming voice calls out “Assalam alaikum, Zahrah. Come to the fire. Drink tea, eat. Come…come.”

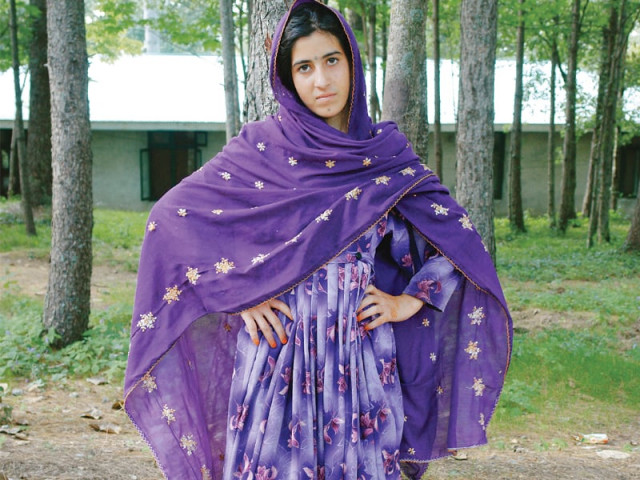

It is my old friend Rabia striding proudly towards me in a heavily embroidered, luminous, pink and green outfit which, I later learn, she has spent much of the summer stitching by hand. Of medium height, slim and wildly elegant, Rabia sparkles with inborn pride, her very walk declaring independence and a freedom increasingly rare in the mad world of today. We generally meet, for no more than a few hours, each spring and autumn when her small tribe passes by here and have been doing so for the last 12 years. Rabia usually sends one of her five children down to invite me to join her or simply drops by on the off chance that I will be home. Each time she has specific bartering plans in mind, along with a proffered gift — the same one twice a year — that she is eager to bestow but which I have yet to accept. This morning was no different.

As we squatted around her smoky camp fire sipping equally smoky green tea and eating piping hot roti sprinkled with melting gur, we firstly, as is customary, catch up on the meaningful generalities of life: The ponies were doing well, the foals were growing rapidly, goats and sheep were nicely fattened on alpine grasses, medicinal and culinary herbs gathered in, stocks of ghee and cheese carefully stored in old oil tins and the like, her children were doing well and her husband — a silent figure wrapped in chador lounging by their makeshift tent — was watchful of his family as always. Once satisfied that I too had brought her up to date about garden and orchard produce, my dogs, work, the wonderful man in my life and an upcoming venture in Afghanistan, we switched over to business. She would trade ghee and cheese for my homemade chutneys; I would trade vegetables and herbs for wild mountain honey; she would exchange an embroidered chador for cloth to make winter outfits for her two daughters; I could borrow a pony for half a day — longer if I liked, as they were resting up for two nights not one, in return for a pair of old shoes for her husband. And then the gift: she would do a beautiful job of decorating my face and hands with tribal tattoos as a mark of friendship and acceptance after which I should walk with them, even winter with them, stay with them for as long as I liked as our ‘sisterhood’ would be complete. All was agreed upon except, as usual, the tattoos and the walk although, I openly admit, both are extremely tempting!

The pony, a dark brown mare with multi-coloured tassels woven into her mane and a highly ornate, embroidered saddle, was more than happy to carry me along twisting forest trails through dripping undergrowth and magical birdsong before enjoying a fast canter along a wide, grassed-over track to yet another camping ground. This camping ground, of a very different nature from the first, had actually been my original destination. A scattering of multi-coloured tents, this camp is the summer home of an extended family of Afghan refugees who customarily sell machine-made chadors, children’s plastic toys and, of late, car accessories, at spots along the side of the main road. I first met one of the men of this particular family in Afghanistan back in 1983, and was astonished when he called out a stunned greeting on The Mall in Murree five years ago. In this camp I am not Zahrah; here I am Banafsha, the Afghan name given to me by the Mujahideen. Here too, I sat around a smoky campfire, drank smoky green tea and unwillingly swallowed the greasy bowl of sheep’s head broth that I was given. At this time — it was late morning by now — the men and boys were all off working, the men selling their wares, the boys collecting recyclable garbage for onward sale so the women and girls were free to chat and laugh. They will not leave for Peshawar, which is where they spend their winters, yet. They will hang on until either the tourists have thinned out badly enough to reduce income to almost nil, or until the nights get too cold for camping out — or until the local people, from whom they rent their campsite, decide that they have had enough of Afghans for now and demand a much higher rent thus forcing them to vacate and move on. These Afghan refugees do not have the herds and traditions of the Gujjars. They will hire trucks, load them up with whatever wares they have left, along with tents and firewood, for the drive to Peshawar. Once there, they will rent a house for the winter and send at least the boys to school for a few months. They are seasonal, economic migrants rather than nomads, yet their way of life draws me too. In this camp we do not barter. Small gifts are exchanged as is customary and here too tattoos are offered and refused along with ear piercings.

My visit with the Afghans over, the pony transported me, through gentle drizzle, back to Rabia’s camp where arrangements were made for her children to come down, carrying Rabia’s half of the bartering, to collect her due. As I walked down the mountain track towards my home, I reflected on just how wonderful and peaceful humanity can actually be.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, September 18th, 2011.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ