PTI’s fate after Imran Khan

Imran Khan is bending the future of Pakistan in his own image

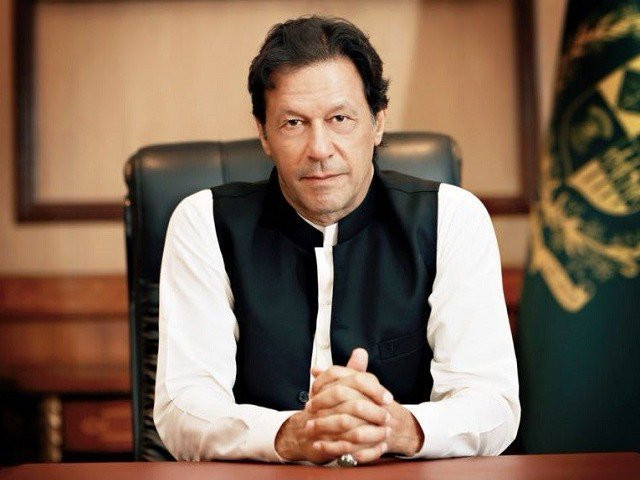

Prime Minister Imran Khan. PHOTO: PID

It’s going to happen one day. So we might as well talk about it now: if Imran Khan is no longer on the political scene, how will it impact Pakistan’s political centre of gravity shifting from feudals to the emerging middle class.

Depending on whether he recedes from the scene after his second term or during his first, one can imagine Jahangir Tareen, Asad Umar and Shah Mahmood Qureshi holding hands together, signalling that they will find a way to keep the PTI’s unruly coalition of politicians together.

Imran Khan’s fading away will also result in the birth of a much overdue, middle-class, political party alternative to the PTI.

According to the great man theory, a 19th century idea, which argues that history can be largely explained by the impact of great men; highly influential individuals who, due to their personal charisma, intelligence, or political skill used their power in a way that had a decisive historical impact, Imran Khan is bending the future of Pakistan in his own image.

In this column, I would like to make the case against the great man theory, arguing that Imran Khan is an outcome, not the cause of dramatic changes in the political consciousness of Pakistan.

Pakistan is a rapidly urbanising country where nearly four in 10 citizens live in cities. These urban citizens are demanding representation in the corridors of power.

When the British colonised India, they wanted to control a large nation, through a few powerful feudal lords.

So, according to legend, they asked the newly-minted feudal lords to ride their horses as far as they could go to mark their boundaries, gifting ownership of this land and all who dwelled within, in return for loyalty to the crown.

As Pakistan became an independent country, these feudal lords continued to chokehold Pakistan’s political economy in their favour.

Today, a rapidly urbanising and educated middle class is finally fighting the chokehold that the feudals have on our country. They’re demanding a voice and the PTI is a primary expression for their point of view.

It’s no coincidence that a man who’s served as dentist to every other upper middle class Karachiite is the president of Pakistan. It’s also not a coincidence that everyone and their mother-in-law have met Asad Umar, our finance minister, at an airport or at a young leaders’ conference.

We want to see people like us in power and the PTI delivers that to some extent.

In short, Pakistan’s middle class was demanding a political voice and the PTI gave an expression to it. The PTI’s success was an outcome of the emerging middle class; not the cause of their emergence. This is fascinating because it has several implications.

First, the PPP and the PML-N need more middle-class representation at the very top of their leadership cadres, otherwise they will become regional, more rural parties (we’re already seeing this with the PPP’s last bastion of support, holding unrelentingly strong, in interior Sindh).

Second, the PTI has been banking on a coalition of feudal electables and clean middle-class men. If the PTI really wants to build a Naya Pakistan, the battle inside the party between middle-class workers and feudal lords will have to turn decisively in favour of the middle-class group.

For the next few years, these divisions can be papered over because of Imran Khan’s charisma. The middle class is overlooking the PTI’s obvious faults because there’s no other political party that can give them representation at this stage.

But once Imran leaves the stage, a middle-class alternative can rise to compete with the PTI. And that, like any healthy competition/opposition, would be good for the country.

Published in The Express Tribune, February 3rd, 2019.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS (2)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ