Does Pakistan have a tipping point?

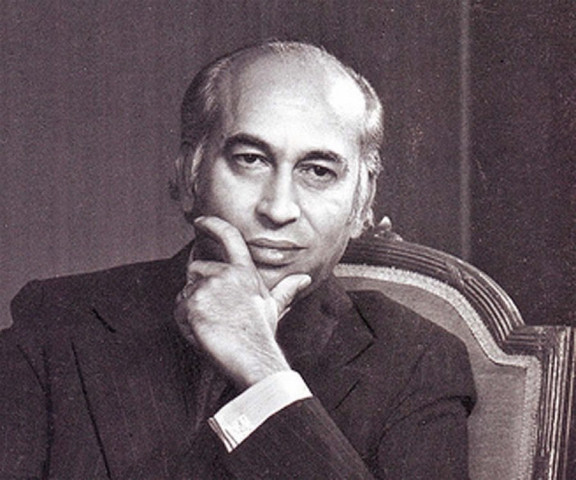

The hanging of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, an elected prime minister, through a mockery of a trial, did not tip us over

The hanging of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, an elected prime minister, through a mockery of a trial, did not tip us over.

Bouazizi’s death became Tunisia’s tipping point. The collective societal conscious awoke the resistance that is now known as the Jasmine Revolution. It led to the fall and exile of Ben Ali’s 24 years of rule. From the Tunisian revolution dawned the Arab Spring.

If we go back in our own history, Akbar, the third Mughal emperor ascended the throne in 1542. The first few years of Akbar’s rule was much like his predecessors. But after a severe illness and recovery, Akbar changed the way he ruled. From 1578 to 1605 he rewrote his reign in history as one of reason. “Reason, not tradition” as historian Abraham Eraly put it meant that Akbar believed in the utmost need to scrutinise political and social values and legal and cultural practices. Akbar’s creation of the ibaatad khana allowed religious scholars from different faiths to come together for discourse and dialogue. He was a Muslim leader working to build a secular and inclusive state.

Whether through the ruled or the ruler, history shows examples of societies changing their course. From kings and kingdoms, societies successfully demand democracy. From generational political and religious rivalries, differing factions sat at the table in an attempt to live in peace in Northern Ireland. From legal and systematic discrimination, people’s movements and struggles led to an eventual apartheid-free South Africa.

For these societies a significant event or an inherit injustice lead them to a tipping point. Questions about collective values, political structure, social set-ups are asked. Do we give up? Do we change course? Do we demand fairness in the midst of injustice? Do we look for peace or descend into chaos?

Does Pakistan have a tipping point? The hanging of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, an elected prime minister, through a mockery of a trial, did not tip us over. The assassination of his daughter in an attack where the tragedy lies in everyone killing her and no one killing her led us to no real change. Salmaan Taseer murdered in broad daylight under the greenery of urban Islamabad and executive bullets did not lead us to the edge. The murder and silencing of women activists and their male counterparts, the one woman army, the ordinary woman killed in the name of honour, the landless farmer tied to injustice and hardship, more than 20 million of children of out of school, the Malalas, the children attacked while in school, the stinking poverty, the disappearance not of the neighbour’s cat but of the neighbour’s son — nothing. Nothing led us, moved us, to the edge. We are not questioning our purpose, our failure, our next step, our new course, our future.

And then this happens. Mashal Khan is dragged out of his university hostel room, under the poster of Che Guevara he had on his wall, to be beaten and shot to death by a mob that filmed and violated him until his lifeless body was no longer a threat. In the very place of learning, where ideas are born, challenged and strengthened became one of the most fatal of spaces. If it can happen in a university, the shrinking space we keep hearing about has now disappeared. It has been superseded with hate and worse, fear. Silence is the new modus operandi. Ideas are now perilous to have and to express. Dissent is dangerous, resistance is futile and non-conformity is sin. Mashal Khan is the tragic example of where we have allowed things to get to.

Politically, we have seen some promise in the form of movements against Ayub Khan and Ziaul Haq but these campaigns failed to take social and cultural values along. The gap is frighteningly stark.

Societies in which fairness is a pillar, carry with them the concept of taking care of others among you. Particularly those that are weaker, more vulnerable, not on an equal footing, that are socially marginalised or unfairly targeted. The cornerstone of the rule of law is justice. John Rawls, the well-known moral and political philosopher, describes justice as fairness. But fairness requires us to think beyond just us. And more imperatively, it requires that we question and denounce mob ‘justice’ and promote and improve real justice through the court system.

If Mashal’s death does not take us to our tipping point towards change, where we collectively stand amongst the “forces of darkness that drown out the light” as so eloquently put by Mashal’s father, Iqbal Jan, then we will head only towards decay. And that says only one thing; that we are wholly and fully complicit to this act against Mashal Khan. The thief lays in our hearts and minds, in our waking thoughts and our dreaming minds. Depravity is our subconscious way of living. It is easier to not challenge injustice because somewhere deep inside either we believe in it or we do not believe passionately enough against it. There is no middle ground here.

Where is our rage? There was political condemnation but too late, too meek, too fearful of the ideological enemy. There are headlines but slowly receding to the back pages. The power of the pulpit is not challenged. The Senate has asked for a repeal of the blasphemy law but who will ask for the repeal to the populist mindset? But rage is not enough. A memory must be attached to it. Pakistan is extremely resilient and dangerously forgetful.

We are looking to blame those to the left, right, in the middle. In fact, our social and political depravation lies within. Morally corrupt and blind to it. Ghalib once famously penned “Umr bhar yehi bhool karta raha, dhool chehrey pay thi, aur aaina saaf karta raha.”

Published in The Express Tribune, April 22nd, 2017.

Like Opinion & Editorial on Facebook, follow @ETOpEd on Twitter to receive all updates on all our daily pieces.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ