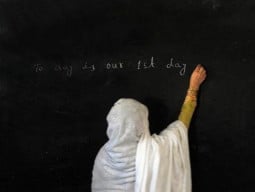

SHANGHAI: A walk through Shanghai Book City draws you into a parallel world of literary traditions.

At a time when the dissemination of knowledge transcends the boundaries of language and the gradual corrosion of culture, the bookstore appears to be an anachronism in these modern times. It maintains a deep and unusual alliance with the country’s mother tongue. The influence of foreign languages was often repelled and pushed towards the fringes.

The seven-storey building has been touted as one of the largest bookstores in Shanghai. Although its shelves are dominated by Chinese books, an entire floor has been dedicated to foreign titles.

I came to know about this store a few hours after I arrived in Shanghai; I had been in China for little more than a week.

My maiden trip to the country had opened the portals to a new vista of literary pursuits. I began reading snippets from the initial chapters of Yu Hua’s Brothers. The novel painted an intimate portrait of lives impacted by the Cultural Revolution in China.

Travel diaries: 10 mouth-watering desserts you must try in Dubai

Through its racy, well-paced and provocative narrative, Brothers revealed the mysteries of a country’s quest for identity and purpose. The themes initiated in this tale echoed through my mind. They drew me into the world of Chinese literature like a flame attracts a moth.

However, my experience at the book city did not take me a step closer to understanding these literary traditions. On the contrary, a trip to the bookstore helped me detect the flaws in the way literary traditions were preserved and immortalised in other parts of the world.

My initial reaction after reading Brothers was to explore the roots of Chinese ideology and its impact on literature. As I browsed through the shelves at the book city, I wanted to find a book on Confucius in English. I had not read the Analects, a compilation of his aphorisms, and was searching for a beginner’s interpretation of Confucian ideology.

Unfortunately, I could not find a single book on the subject at the store. I climbed seven flights of stairs but was only greeted with books bearing Chinese characters that were foreign and unfamiliar.

As my quest for an English translation of Confucius’ work appeared futile, I found myself struggling to sustain the illusion that knowledge could break the barriers of language and conquer a common ground.

Over the years, English had provided a lens through which I could gain an insider’s view of a foreign world. Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s words had spoken to me of a hundred years of solitude and a colonel who no one wrote to. These words had instantly found residence in me even though they had been written in another language. Could my experience with the translated works of Confucius be any different from reading Marquez’s work?

After my initial disappointment began to ebb, I realised how a language can preserve the secrets of a culture. In an age when diaspora fiction remains widely popular, ideas are likely to lose their essence in translation. More often than not, the politics of translation can change the course of literature and distort its vision of reality. The clumsy, unremarkable attempts to find meaning in the works of Sufi mystics are a case in point.

Travel diaries: You can check out any time you like but you can never leave

Elif Shafak’s The Forty Rules of Love never fails to shed the reserve of imagining the world of Jalaluddin Rumi and Shams Tabrizi. Her intricate rendering of the past has attracted wide readership across the world. However, the novel does not succeed in upholding the weight of tradition in the face of modernity. As a result, Shafak’s depiction of Shams bears a strong resemblance to yoga teacher who aspires to achieve a superficial realm of nirvana.

The cultural nuances have not been presented in a clear and consistent manner. As a result, The Forty Rules of Love gives into temptations and cashes in on Rumi’s popularity in the West. The underlying essence of Rumi and Shams’ work was lost in translation.

As my mind drifted towards these thoughts, the purpose of establishing a deep allegiance with a particular language did not seem discriminatory or unnecessary. When I returned home, I shelved my copy of Brothers as I feared I would either misinterpret its essence or fail to fathom its hidden layers.

The writer is a staffer at The Express Tribune

Published in The Express Tribune, July 10th, 2016.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

COMMENTS (1)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ