Factory fires: Smoke and Mirrors

Factory fires have claimed hundreds of lives in Pakistan, yet little is being done to prevent a tragedy like Baldia

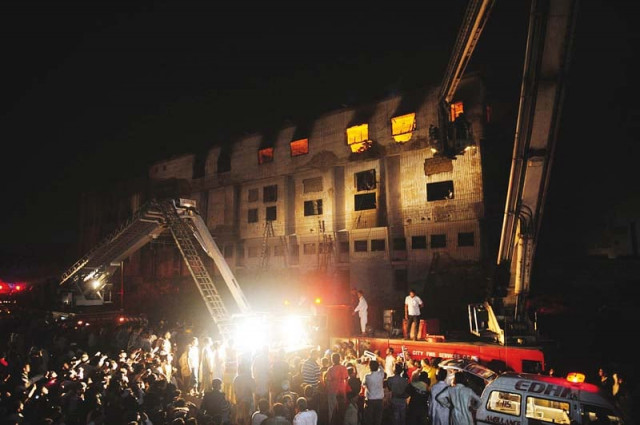

The Baldia factory fire on September 11, 2012 took 260 lives and left another 600 injured. PHOTO: AFP

Protecting the labour force at factories is a collective effort by all stakeholders, including owners, contractors, subcontractors, suppliers, consultants, regulatory bodies and non-governmental organisations. However, failure to implement adequate safety measures poses a serious hazard for those working in risky environments, and they’re paying for this with their lives.

The fire at the garment factory of Ali Enterprises in Baldia Town erupted when a boiler exploded and chemicals stored on the premises fuelled the resultant flames. According to Section 23 of the Factories Act 1934, every factory should have an appropriate fire exit. Yet, what transpired on that September day was the first of a drawn out exercise of smoke and mirrors. “There was only one exit and my son was left in a helpless state, waiting for his death,” says Abdul Aziz Khan, father of 19-year-old Attaullah Nabeel who died in the fire.

Many workers suffocated to death when dense smoke engulfed the factory basement. The owners reportedly shut all exits except one in fear of their merchandise being stolen. Workers present on the upper floors of the five-storey building tried to somehow bend or break the metal bars on windows, jumping out of any open space that would allow their bodies to pass through.

Grave as it was, the tragedy was only exacerbated by another fire at a shoe factory in Lahore the same day. The two-storey building was constructed for residential purposes but was illegally being used commercially. Around 25 people were killed in the incident. One would think the two fires would be enough to stir entrepreneurs and the government to strive and eliminate the possibility of any such tragedies in the future. But unfortunately, few, if any, lessons were learnt.

According to a consolidated report on fire emergencies (2007-2012) released by Punjab emergency service Rescue 1122, fires erupted due to short circuiting in 5,876 factories, industrial units, houses, shops, shopping malls and trade markets in Lahore, followed by Faisalabad with 2,500 and Rawalpindi with 1,335. Recklessness and smoking were the reasons behind 578 fire cases in Multan, 333 in Gujranwala and 323 in Sahiwal.

There have also been multiple factory fire incidents this year. On February 17, a fire erupted at a shoe factory on Khayaban-e-Sir Syed in Rawalpindi. A short circuit triggered the fire which spread in the presence of plastic shoes and chemicals. No casualties were reported but the factory sustained an estimated loss of Rs0.5 million.

On June 3, 2015, a fire broke out at a towel factory in New Karachi. The flames engulfed all three floors of the building and soon spread to another towel factory next door. It took more than 10 fire tenders and a snorkel to dowse the blaze, which was a declared a third-degree fire. Another fire erupted on June 24 this year at a shoe warehouse in the Sher Shah area of Karachi. Fire fighting officials categorised this too as a third-degree blaze. On July 22, a fire broke out at a towel factory in Karachi. It took around seven hours for the fire fighters to put out the blaze. Fortunately, no loss of lives was reported in any of the incidents.

Cutting corners

Ali Enterprises was not registered with the Directorate of Labour as required under Section 9 of the Factories Act 1934 and Section 3 of Factories Rules, nor was the building’s structure lawfully approved by any authority. A majority of the workers did not have appointment letters and were not registered with the Employees Old Age Benefits Institute (EOBI). Almost all of them worked under an illegal third party contract system, without any collective bargaining rights in the absence of a trade union. Work hours ranged from 10 to 14 a day without any provision for overtime pay. Records show Ali Enterprises had officially registered just 200 workers, when in reality, over 1,500 people toiled in the factory.

The fire at Ali Enterprises erupted when a boiler exploded and chemicals stored on the premises fuelled the resultant flames. PHOTO: AFP

President of Baldia Factory Fire Affectees Association and father of 22-year-old Muhammad Jahanzeb who died in the incident, Muhammad Jabbir is still scrambling for monetary compensation. “Nawaz Sharif promised to pay Rs300,000 to every victim’s family, but we still haven’t received anything from him,” Jabbir says of the prime minister, who assumed power nearly a year after the unfortunate event. However, Jabbir acknowledges the compensation given by others. The factory owners paid Rs200,000 to bereaved families, while German company KiK paid Rs500,000. The government also gave Rs200,000 as group insurance while business magnate Malik Riaz paid Rs200,000 to half of the affected families.

It is not just about money. Many lost their family’s sole breadwinners so financial considerations are a major factor in their quest for justice, but the apathy of different stakeholders in ensuring this does not happen again is a greater cause for their anger.

At present, there is a case being pursued against German company KiK, which purchased 80% of the goods produced at Ali Enterprises, while Italian audit firm RINA is also facing litigation over the issuance of a clearance certificate right before the incident. While RINA claims it sent subcontractors to visit and inspect the factory in August 2012, Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (Piler) Executive Director Karamat Ali maintains RINA gave the factory the SA8000 certification — meaning that it met international standards in nine areas, including health and safety, child labour and minimum wages — without even carrying out an inspection.

Dormant labour laws

Though Pakistan is a signatory to many international labour conventions, they are hardly implemented by factories. The only legislation on health and safety is the Hazardous Occupation Rule 1963 under the Factories Act 1934. The act consolidates and amends laws relating to the regulation of labour in factories in the country. It includes the role of labour inspection, restrictions on working hours, holidays with pay, special provisions for adolescents and children, penalties and procedure. It also contains a chapter on health and safety of workers and hygiene conditions at workplaces. Chapter III of the act includes laws on factory inspections, hygienic conditions (ventilation and temperature, dust and fumes, artificial humidification, lighting, overcrowding, drinking water, sanitary facilities), precaution in case of fire, and precautions against dangerous fumes, eye protection, safety of building, machinery and manufacturing. However, these laws are practically obsolete and do not conform to international practices.

Men grieve for their relatives after the factory fire at Baldia Town. PHOTO: AFP

Pakistan ratified the ILO Labour Inspection Convention (1947) in 1953. Under this convention, Pakistan is bound to educate and inform employers and workers on their legal rights and obligations concerning all aspects of labour protection and labour laws, advise employers and workers to comply with the requirements of the law, and enable inspectors to report to superiors on problems and defects that are not covered by laws and regulations.

“Most of the problems in the industrial sector are with regards to wages, working conditions, occupational health and safety at the workplace, and the right to form a trade union and bargain collectively,” explains Deputy General Secretary of the National Trade Unions Federation, Nasir Mansoor.

According to a report published in 2013 by the Employees Old Age Benefit Institute and the Sindh Employees Social Security Institute, only 3% of workers have appointment letters, while only 4-4.5% are registered under the social security institute responsible for health care of workers and their families. Similarly, only 4% of workers are registered with the Employees Old Age Benefits Institution and the Workers Welfare Fund.

Agrarian workers, who comprise half of the labour force, are not covered under any scheme as they are not considered workers under labour laws anywhere except in Sindh. Hence, they have no right to form a trade union or to fight for labour related rights.

On the other hand, international brands use the ISO and social auditing certifications through international audit firms and code of conduct mutually signed with local manufacturers as a smokescreen to avoid the responsibility of implementing local labour laws and ILO conventions.

Ensuring a safe work environment

Piler Executive Director Karamat Ali cites lack of awareness regarding legal provisions pertaining to the rights of workers as one of the major problems affecting the safety and wellbeing of factory employees. “The employer is responsible for displaying provisions of the law inside the factory in languages the workers understand,” he says.

Precautionary measures at Searle Pharmaceutical Company to fight small fires. PHOTO CREDIT: ARIF SOOMRO

To prevent such fires, a site safety manager should establish fire-fighting facilities and ensure trained personnel are available in case of any emergency. An evacuation plan also needs to be implemented, says Ali. A chief fire officer should be appointed to assist the safety manager, impart effective practical training to fire fighting teams and coordinate with the city fire brigade and civil authorities.

Though most factories completely disregard such precautions, some like Searle Pharmaceutical Company in Karachi have strived to ensure adequate fire fighting facilities. The company has a fire hydrant system which consists of underground water tanks, pumps and pipelines. There are three underground water tanks of 45,000, 35,000 and 10,000 gallons, respectively.

Proactive companies like Searle, however, are few and far between. To ensure a tragedy such as Baldia Town doesn’t take place again, every factory owner needs to take the onus of securing their employees. Unless that is done, we will have only ashes to contend with after each such fire. Ashes from which no phoenix will rise.

Komal Anwar is a subeditor at The Express Tribune magazine desk.

She tweets @Komal1201

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, August 2nd, 2015.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ