A mission in Makran

French archaeologist Aurore Didier reveals how Pak-French Archaeological Mission in Makran will benefit both nations

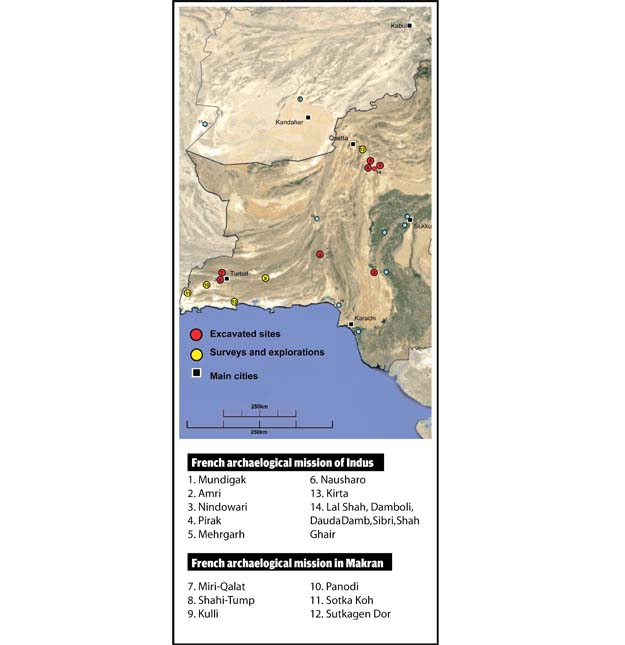

Pakistan has enjoyed close bilateral ties with France since decades. Be it military, cultural or educational cooperation, the two nations have found common ground, which has ultimately made their relationship stronger. Apart from encouraging students to take up French at university level in order to pursue a post-graduate education in France, Pakistan has steadily invested in its mutually beneficial relationship by inviting French archaeologists to unearth a 8,000-year-old civilisation in Makran and to promote the study of archaeology in both nations.

The Indus civilisation or Harappan civilisation, first identified in 1921, was widely recognised as the Indian subcontinent’s earliest settlement. But the discovery of an agricultural centre in Mehrgarh, Balochistan, dating back to 7,000 BC, changed that. Discovered in 1974 by French archaeologists Jean-François Jarrige and his wife Catherine, who had been working in Balochistan since 1964, the site represents a highly-developed civilisation that predates the Indus civilisation.

After the demise of Jean-François Jarrige in November 2014, his widow chose another woman, Aurore Didier, to continue the work the couple had started. “Aurore is a brilliant scholar whom my late husband and I have chosen to continue with our archaeological work, look after our files and documents and to publish the findings,” says Catherine.

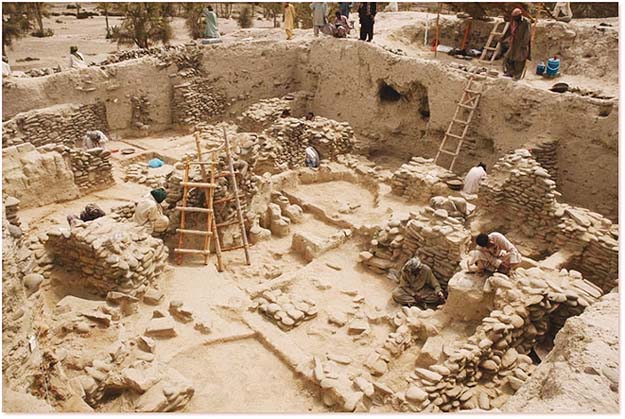

Didier first came to Pakistan in 2000 as a member of the Pakistan-French Archaeological Mission in Makran, directed by Dr Roland Besenval, founder of the Mission in Makran from 1987 to 2012. “At the time, I was a Masters student at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, focusing my research on the Indus civilisation,” she says. “This was the only French mission that was carrying out archaeological work in Balochistan; so, I worked at the site of Shahi Tump near Turbat, in Kech-Makran district, as in-charge of excavations with other archaeologists.”

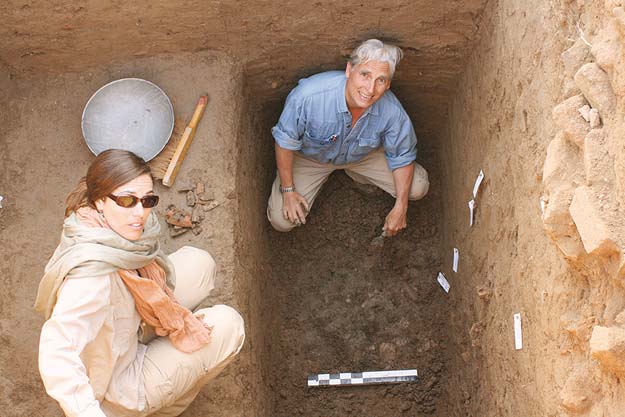

Neolithic settlement (7,000 BC) in Mehrgarh. PHOTO COURTESY: CATHERINE JARRIGE

Excavations by the French Archaeological Mission in Makran (1990-2007) in Shahi-Tump. PHOTO COURTESY: AURORE DIDIER

Didier always shared a warm relationship with Catherine and Jean-François Jarrige. “I was honoured when Jean-François and Roland Besenval asked me to supervise the mission and later to head the Indus-Balochistan programme,” says Didier, who has previously worked at an archaeological site in Turkmenistan and was a member of the French-Indian Archeological programme in Ladakh for two years as in-charge of pottery studies.

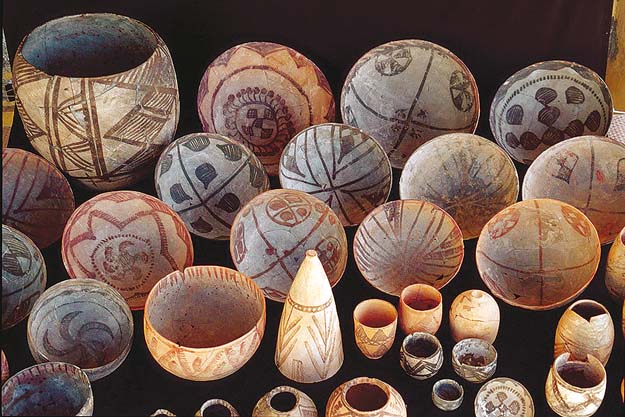

Soon, Didier concentrated on ancient pottery from the 3rd millennium BC in Makran and decided, with the support of Roland Besenval and Jean-François Jarrige, to do a PhD in ancient pottery. She divided her time between Pakistan and France, spending January to April in Makran from 2001 to 2007. She coordinated with the Sindh government’s Exploration Branch on the materials found during the excavations.

Didier is currently working on the publication of final results of the work conducted in Makran. “For the next five years, we plan to publish the final results of the Shahi-Tump excavations and also of the environmental programme conducted on the Makran coast,” she adds.

Balochistan and the southern Sindh connection

Didier is currently not able to work in Balochistan due to security concerns in the province. “We have no authorisation to go there from the French and Pakistani authorities,” she says. “We don’t want the people or government to get uncomfortable. After we stopped the research in Makran, we came back to study the findings there. We have also launched French Archaeological Mission in Indus Basin, supported by Jean-François Jarrige and Roland Besenval.”

She points out that Sindh was the starting point of French archaeological research on the cultural heritage of southern Pakistan for the protohistoric period (around 1,400-1,500 AD). The research was initiated at Amri by Jean-Marie Casal in 1958. “After working in Balochistan, we came back to Sindh to continue this research,” says Didier.

Didier and her team are presently focusing on details of transition linking pre-Indus and Indus civilisation periods, finding a connection between ancient cultures of Balochistan with that of Sindh, which includes how the Indus civilisation developed on that site and what the relationships between the different regions of the Indus territory and Balochistan’s culture were.

Funerary pottery from 2nd half of the 4th millennium/beginning of the 3rd millennium BC found in Shahi-Tump. PHOTO COURTESY: AURORE DIDIER

Aurore Didier and her colleague Dr Pascal Mongne working at a prospective site in Sindh that could be excavated in the next field mission. PHOTO COURTESY: AURORE DIDIER

“In Makran, we have shown some link among the chalcolithic, Bronze Age period,” she says. “This mission put together the scientific programme conducted by Besenval in Makran with a new programme on Indus, developed in collaboration with the Culture, Tourism and Antiquities Department, Government of Sindh. But the topic and the issues are the same as conducted before in Balochistan. The issue is to try to find more data, have new information concerning the inter-regional interaction system between the Indus Valley and Balochistan. That means new exploration and excavation in Sindh.”

The team also aims to carry out improvements in the chrono-cultural periodisation of southern Sindh, which is currently not well-known: “The only sequence available with chalcolithic, pre-Indus and Indus periods is at the site of Amri in southern Sindh, in Ghazi Shah and Kot-Diji, but there was no other excavated site which had the potential for studying the transition between the pre-Indus and the Indus civilisation periods,” Didier explains.

Didier shares that while searching for a suitable area for excavation, the team noted protohistoric sites in Sindh. “The problem with many sites in this valley is that it is very difficult to reach the deepest level of these sites (like in Mohenjo Daro where some work was carried out in the 1920s),” she explains. “The level of alluvial plain and the water is too high to be able to go deeper and to study the oldest level [which may reveal] the transition between pre-Indus and Indus periods. “Due to technical difficulties, those levels are not reachable at the moment and we cannot substantiate the presence of a settlement before the Indus civilisation buried beneath the Mohenjo Daro remains,” Didier says. Catherine Jarrige adds, “There are probably pre-Indus levels at Mohenjo Daro, but they are under the present water-table.”

Late Jean-François Jarrige and Catherine Jarrige at Musée Guimet in Paris. PHOTO CREDIT: MM ALAM

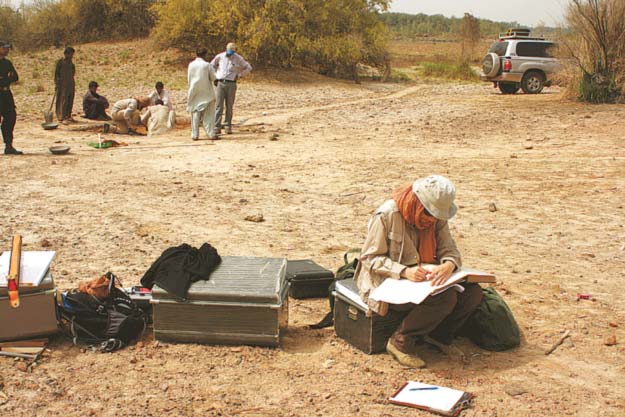

Aurore Didier during a field study in 2015 in Sindh. PHOTO COURTESY: AURORE DIDIER

Commenting on the objective of the recently-launched Indus Basin Mission, Didier says, “We would like to explore these new sites and try to select a site which could have pre-Indus and Indus levels with the help of the government’s Exploration Branch.” She indicated that being close to Balochistan, Jamshoro is a perfect area to work on the southern Sindh and Balochistan connection.

It’s a team effort

According to Didier, the team will coordinate with local experts to use and develop innovative technologies to conduct their research work. “One of the most important things is to train the new generation of archaeologists both in France and in Pakistan,” she feels. “In our next field campaign, to be conducted jointly with local archaeologists from the government’s Exploration Branch, Culture, Tourism and Antiquities Department, we will systematically include Pakistani students from different universities (particularly here in Sindh) to train them to become future archaeologists. We are working on the cultural heritage of Pakistan but it is also our duty to train locals and give them access to information.”

Didier says her mentors have always emphasised the importance of involving locals in her research: “During our week-long exploration at Chanhu-Daro this year, people visited and asked positive questions. One man also read a poem in Sindhi, praising our work.”

Speaking about sources of funding, Didier says, “We are working in close collaboration with the Embassy of France and with the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs.” With the support of the diplomatic mission here it will be possible to send Pakistani students to France and bring French students to study archaeology in Sindh’s universities.

Bridging the gap

Noting that the cultural heritage of Pakistan is a fantastic field for archaeologists, Didier says, “I believe the French Archaeological Mission in cooperation with the Department of archaeology and Museums of Pakistan has made an effort to show the richness of this ancient history.” Yet, she laments that there is a lack of awareness in France about the South Asian protohistoric archaeological importance. “The first time I heard fleetingly about the Indus civilisation, it was in university during a course concerning Middle East archaeology and trade in the 3rd millennium BC.” Didier plans to introduce the Indus civilisation as a subject in French institutions and create awareness through talks at various forums.

She also plans to organise international seminars, conferences and exhibitions both in Pakistan and France. In next five years, with the help of Pakistani partners, she will endeavour to organise an exposition at the Musée Guimet at Paris featuring objects of Pakistani heritage, especially the Indus civilisation and the chalcolithic period in southern Pakistan. “It would be fantastic for us to have an exhibition about the material from Makran, Mehrgarh and Naushahro,” she says.

MM ALAM has been actively involved in journalism since 1991. He is a Karachi-based staffer at The Express Tribune.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, April 12th, 2015.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ