Of the two preeminent bookstores in the metropolis, one has mastered the art of fleecing the public by selling second-hand books at first-world prices, while the other is manned by staff who seem to make a concerted effort to irk customers to ensure that they leave never to return. It was at the former that yours truly chanced upon an inconspicuous book inappropriately shelved in the poetry section while scouring the shelves of the establishment to find something interesting to read.

Little did I know then that I had chanced upon a stellar translation of a forgotten novella penned by Urdu poet and writer Mirza Muhammad Hadi Ruswa soon after the publication of his magnum opus, Umrao Jan Ada in 1899, which is widely considered to be the first novel in Urdu. While Umrao Jan Ada has been hailed as one of the finest specimens of Urdu prose since its publication and has remained etched in public memory due to its various cinematic adaptations, Junun-i-Intezar or The Madness of Waiting, wherein the courtesan reveals details of Ruswa’s affair with a European woman to even scores with him for having the temerity to publish a fictionalised account of her life was consigned to oblivion. But Junun-e-Intezar and Umrao Jan Ada are not the only works by Ruswa on the courtesan’s life. The lesser-known Afsha-i-Raz precedes them both.

Krupa Shandilya, who teaches at Amherst College in the United States, became cognisant of Junun-e-Intezar over the course of her research on Umrao Jan Ada. Shandilya was on the cusp of abandoning her effort to trace the lost sequel when she came across a reference to the text on Carnegie Mellon’s million book project. An additional lead took her to the Salar Jung Museum in Hyderabad where she found a derelict copy of the novella after scouring the museum for hours. International border controls and the need to collaborate with someone well versed in Persianised Urdu compelled Shandilya to affiliate with Taimoor Shahid, a scholar and translator, over the text. The collaboration culminated in a superlative book that includes the original text, a translation of it in English and a lucid introduction that contextualises Ruswa’s work.

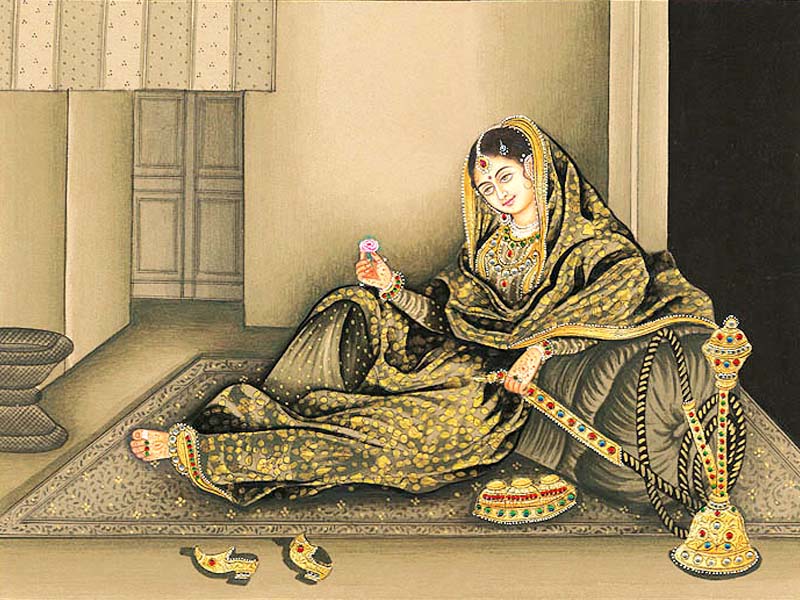

The significance of this service to literature cannot be emphasised enough. The publication of the novella fills a gaping void regarding the evolution of Umrao’s character in Ruswa’s work in addition to reinforcing two key points. The recovery of the novella enables the reader to chart the development of the courtesan’s character in three of Ruswa’s works. Fleetingly referred to as a dancing girl of some merit in Afsha-i-Raz, Ruswa’s first work which mentions Umrao, she is portrayed as a woman of many gifts in his Junun-e-Intezar. Among the many talents she is shown to be possessing, Umrao is depicted as a poet composing verses in rekhta, the standard register used by Urdu poets to compose verses, in contrast to rekhti, another genre of Urdu poetry that became primarily associated with the language of the women of the bazaar over time. In Junun-i-Intezar, the dancing girl of Afsha-i-Raz and the poetry-composing courtesan of Umrao Jan Ada evolves into a narrator. A woman compelled to avenge her honour by putting pen to paper.

Furthermore, had the forgotten text not been digitised by the Digital Library of India, it is highly likely that efforts to retrieve it would not have seen the light of the day. This refutes the enduring debate in academic circles regarding how modern technology has hastened the demise of the written word. Instead, in this case, technology can be said to have played a pivotal role in enabling the preservation and reintroduction of an important work. Moreover, in the introduction to the novella, Shadilya informs the reader that the internet facilitated the timely conclusion of the text’s translation by facilitating communication between her and Shahid. This enabled them to collaborate over a project that was essentially international in nature and surmount national divides and a strict visa regime.

Lastly, the fact that two people hailing from India and Pakistan collaborated over the translation is a befitting tribute to the composite legacy of Urdu. A language which in the eloquent words of Zakir Hussain, a former Indian president, “…is not the language of a community or religion; it was not imposed by any government…It is the language of the common people…It is not startled by what is novel, it does not shy at innovation, it does not consider any words as polluted.”

Published in The Express Tribune, March 15th, 2015.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

1719315628-0/BeFunky-collage-(8)1719315628-0-405x300.webp)

1731329418-0/BeFunky-collage-(39)1731329418-0-165x106.webp)

1731746614-0/Untitled-design-(14)1731746614-0-270x192.webp)

1731744038-0/Untitled-design-(10)1731744038-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ