Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia: In differences, we grow

The pluralistic display at museum does justice to diversity within the ‘Islamic’ category

Apart from the priceless relics therein, the site itself is a prized work of art. The domes of the museum show up prominently amongst the mesh of flyovers and skyscrapers of Kuala Lumpur. They are done in cobalt blue, white and turquoise to represent the characteristic bright hues of the art found in Islamic lands towards the end of the medieval ages. The rest of the façade is designed in a clean and modern scale, with squared edges, glass walls and ample windows cleverly positioned to allow for a steady flow of sunlight even to the halls located deeper inside. The roofs of the galleries are adorned with huge domes coloured in peach, light blue and cream with gold and silver embellishment.

A 17th century AD Iznik pottery tile from the Ottoman Empire

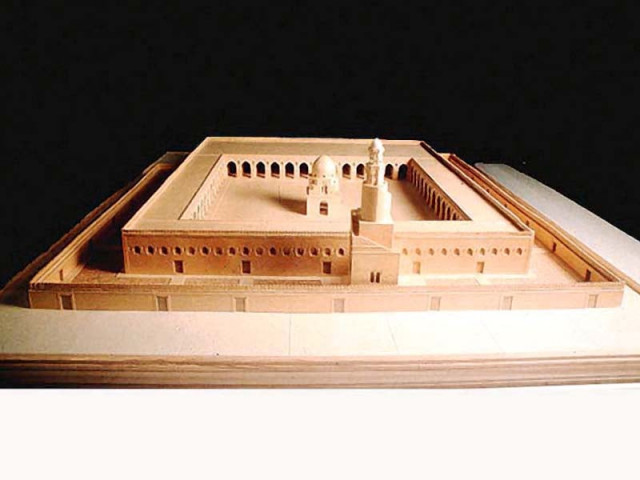

The museum displays a comprehensive collection of scale models to emphasise the importance of architecture in Islamic cultural identity

The display or artifacts and relics make it obvious that the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia is committed to Southeast Asia’s Islamic heritage, which often remains excluded from the discussion of Islamic history. “When you say Islam, you think Saudi Arabia, you think Iran and Iraq. Rarely would you think of the Malay peninsula or Indonesia,” says Christoph Hills, a German researcher and visitor to the museum.

The building is divided into 12 galleries, dedicated to India, China, the Malay world, ceramics, architecture, Holy Quran and manuscripts, coins and seals, metal work, woodwork, textiles, jewellery and arms and armour. The gallery on the Malay world features pottery, manuscripts and woodwork bearing the name of the Holy Prophet (pbuh) and praises of the panjatan — the Holy Prophet (pbuh) and his family. There are engravings on wood of select passages from the Holy Quran. Most important to the collection are the many scrolls with scriptural verses done in calligraphy — an art form that thrives in Malaysia but has often remained overlooked. Though calligraphy originated in Arabia in the form of the Kufic script, it underwent many modifications as Islam spread across different cultures.

Scaled miniature models of a number of Islamic shrines and mosques are displayed in the architecture gallery

In Islam wood has been a canvas for two-dimensional creativity and used by craftsmen to render geometric and calligraphic forms

Southeast Asia, the most easternly end of Islam, has its own distinct style of ornate writing which is said to have originated in the 1300s and is heavily derivative of the calligraphic trend of both India and China. Moreover, painted textiles, tiles and pots hailing from the Malacca Muslim sultanate in Malaysia (1400-1511) seem distinct owing to the softer artistic themes of fruits, plants, rains, clouds and other elements of nature. Ceramics coming out of Persian lands in the same era featured more aggressive imagery, such as hunters or even dragons. The Islamic trends of Malay Archipelago are, curiously, more influenced by missionaries hailing from the Indian coastline than by the Muslim institutions of China, despite the territorial proximity of the latter.

The ceramics gallery displays the works of Muslim potters that range from the Nishaphur calligraphic bowls to the Kashan lustrewares

While giving the Southeast Asian Muslim identity its due representation, the Islamic Arts Museum allows ample space to relics from other key Muslim geographies as well. While allowing for aesthetic pleasure, a pluralistic display of the sort also has some political utility since it gives a fair representation of the cultural dissimilarities within the ‘Islamic’ category. From the displays of scrolls inked with praises of the Holy Companions and God in other-worldly terms, the museum visitor is able to move almost immediately towards historical tomes on botany, medicine and physics hailing from the Abbasid, Fatimid, Seljuk and Ottoman empires. The contiguous positioning of these texts in the gallery allows one to experience the cosmic and the pragmatic elements of Islamic heritage simultaneously.

The China gallery includes the cloisonné wares that China started to create in quantity during the 15th century

The collection from India consisted largely of woodwork — lavishly carved thrones and mimbars (a pulpit in the mosque where the imam stands to deliver sermons) from the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal-era. The engravings were often praises of the ruler in Urdu or Persian script or ornate patterns of leaves and flowers. A key relic of this collection is a sword and a powder flask from the personal armoury of Tipu Sultan (1750-1799), the Muslim king of Mysore.

The most captivating aspect of the museum is the architecture gallery. Here, scaled miniature models of a number of Islamic shrines and mosques are displayed. The accuracy of these models is startling to the beholder. Everything from the famously complex positioning of the tiles of the Nasiral-Mulk Mosque in Shiraz, Iran to the spiral minaret of the Ibn-e-Tulun mosque, Cairo has been modeled, somewhat accurately, into cardboard and wood. Mosques from various other Islamic lands have also been modeled, allowing for a valuable study of the similarities and differences of Islamic art to visitors.

Photos courtesy: Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia

Faiza Rahman is a subeditor for the Opinion & Editorial section of The Express Tribune.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, November 9th, 2014.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ