The tale of the Pashto dastaan

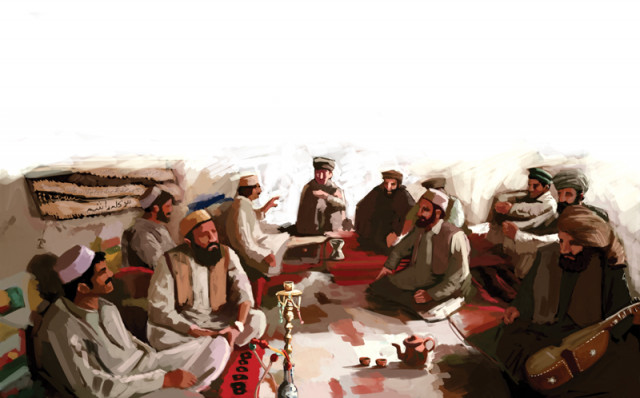

Narrative poetry set to music, the dastaan or badala, gained prominence in hujra gatherings.

The tale of the Pashto dastaan

Those who know about the pains of true love,

They will not strive after an (love) affair,

O people it is indeed paradise on earth,

If one has one’s beloved (sitting) by his side.

Death treats old and young alike,

God Almighty cares not about your financial status,

Dividing mankind on the basis of high and low caste is our work,

Otherwise we all descended from one Adam.

(An excerpt from Ali Haider Joshi’s work Yousaf Khan Sherbano)

A typical opening stanza of a badala as it is known in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (K-P) and the adjacent tribal belt would typically hit the right mix of love, discord, and of course, heartbreak.

Also known as a dastaan (chronicle) in Afghanistan and by academics in Pakistan, the badala often spins stories around popular romances like Laila Majnoon, Adam Khan Durkhanai, Yousaf Khan Sherbano and Sher Alam Mamonai. Often sandwiched in between or pegged to the beginning, comes a stanza with a moral behind it. In the one mentioned above, the badala starts with the pains of love and goes on to discuss social equality. Poets would add such stanzas to either increase the poem’s length or use the popularity of a dastaan to propagate a message with social values.

From the hujra to TDK 60

The Pashto badala has been around for hundreds of years. Before the badala’s golden age was ushered in with the arrival of audio tapes in Peshawar in the 1970s, this poetry form was the star attraction in majalis held in hujras. More so in the region where Pashto is spoken and understood than the rest of Pakistan.

With the popularity of audio tapes, the badala left the hujras and started reaching a widespread audience, set to music.

Also in this period, great singers likes Wahid Gul Ustad, Syed Muhammad, Abid Noor and Fazal Qayum came to the fore, gaining more fame than ever as they were considered specialist dastaan singers.

In the 1970s, Ali Haider Joshi and Ewez Khan emerged as leading ‘awami’ poets as they rewrote the dastaans of Yousaf Khan Sherbano, Sher Alam Mamonai, and Adam Khan Durkhanai. This time, the dastaans were written in the more popular vernacular as opposed to the language of the literary aristocracy.

Even in its written form, this poetic genre is much older than the pop culture of the 70s. Some say it reached its zenith in the 18th century.

According to Pashto ki Manzoom Dastanain, a booklet written by Muhammad Javed Khalil and published in 2008 by the Pashto Academy in collaboration with Lok Virsa, “The real history of the Pashto dastaan is much older.

It started appearing in the written form around the end of 1100 and start of 1200 AH (Islamic calendar). It was then that the local poets translated these classic romances from other languages, especially Arabic and Persian.”

The document goes on to add, “As per available evidence, the dastaan of Laila Majnoon written by Sikandar Khan Khattak in around 1090 AH is the first of its kind.” These were followed by Talib Rashid’s Gul Sanober, Abdul Qadir Khattak’s Yousaf Zulaikha (1112 AH) and Nereng-e-Ishq and Shah wa Gada by Abdul Hameed around 1137 AH.

While many of these badalas revolved around the classic romances of the culture, some of them were purely fairy tales; mythical stories like Nembola Tembola and Deo Toraban, translated from other languages.

Fading out translations

This age of translations was soon followed by native dastaans. These poems included Yousaf Khan Sherbano, Fateh Khan Rabia, Momin Khan Shernai, Tor Dil au Shahai and Mosa Khan au Gul Makai.

For centuries, many Pashto poets concentrated their penmanship on dastaans. Such poets included Mullah Ahmad Jan, Maulvi Ahmad, Ahmad Khalil, Ali Haider Joshi, Mullah Ahmad Turabi, Maulvi Gul Ahmad, Mullah Naimatullah, Syed Abu Ali Shah, Abdur Rehman Qazi, Abdul Ghafar Malang, and Noorullah Yousafzai.

Talking to The Express Tribune, music enthusiast Ali, from Peshawar, said previously Pashto dastaans were limited to books and hujra majalis, “but with the arrival of cassettes, music centres started investing in tapes with the dastaans set to music. It became something to be found in every household.”

“Back then, we saw Ajab Khan Afridi’s dastaan sung by Abdul Wahid Ustad become an instant hit. Some music centres tried to be more innovative and paid poets to write new dastaans. I heard the dastaan of Adam Khor during Ziaul Haq’s reign.”

According to Ali, “Even when the well-known criminal Olasay was killed in an encounter in Badhaber, a dastaan about him was soon available at these centres in which he was portrayed as the voice of the oppressed.”

But the age of the dastaan in its music form has now come to an end, with the CD replacing the iconic plastic cassette tapes,” complained Ali.

“The singers, poets and most importantly, the music centres that promoted such activities are not there anymore – I can count five centres on Cinema Road where previously there were at least 25. This is excluding Kabari Bazaar and Jalil Kababi Road.”

Even dastaans about religion – sans music – are nowhere to be found now. With the death of the tape and the penetration of internet and television in public spaces and hujras, the badala has become an art of days gone by.

Published in The Express Tribune, June 30th, 2014.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ