There is something brutally honest about the bulk of work done by the quintessential modern playwright Mark Ravenhill. It’s a raw scream of human emotion. No one can dispute Ravenhill’s prowess and commitment to daring forms of political theatre available in the mainstream.

Consciously or unconsciously, he seems to be in many ways a descendent of Bertolt Brecht, and some would say that the similarities of the play’s structure are uncanny to Brecht’s Fear and Misery, in which the rise of fascism becomes a prevalent theme. This is why the 2007 Edinburgh Theatre Festival has been etched into the memory of many theatre enthusiasts. Titled Shoot/Get treasure/Repeat, it was a six hour long performance that included 16 plays, boldly critiquing the idea of how the themes of war have become socialised in our everyday lives.

In the local context, the decision by Sarmad Khoosat and Nimra Bucha to adapt this for a Pakistani audience was a daring prospect. Performed in front a small crowd at the NCA auditorium, it is reduced to three, short 20 minute plays for the short attention span of the art-loving elite.

There is a disclaimer for the politically correct and innocent minds that the play is filled with expletives, and it would not be advisable for children to watch. The opening scene of Shoot/Get treasure/Repeat, which is titled Fear and Misery, is of a couple played by Sarmad Khoosat and Nimra Bucha. The first scene starts with the intimate yet casual conversation of how their child was conceived, only to disintegrate into a confrontation as they are slowly forced to reveal their darkest secrets.

The immediate chemistry between Bucha and Khoosat shows that they have worked together consistently on a variety of projects. In fact, the decision to produce this seems to have arisen from the yet-to-be released film Manto. One could suggest that this may be an attempt to steer away from the shallowness of television drama, both pushing their boundaries as theatre artists to create a unique and uninhibited atmosphere.

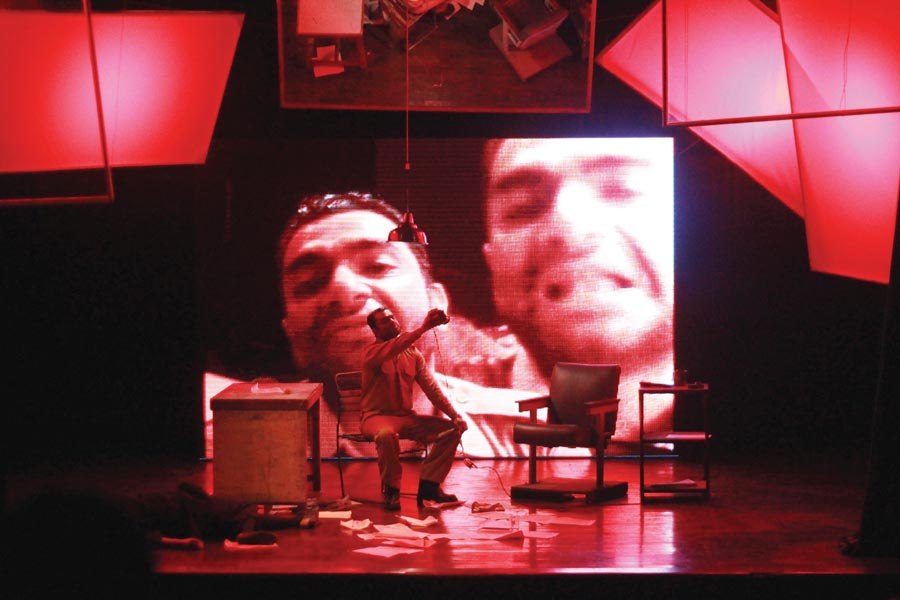

An angled mirror hangs above the stage, as if to distort and poke fun at the realities of life. The scale, naturally, cannot be compared to the original, which includes a live sound-operator and projectors with images of war. Khoosat and Bucha instead utilise a handheld camera and stage settings to set the tone.

The second play, War and Peace, includes a stand-out performance by Adnan Jaffar, who plays the role of a headless soldier who visits the room of child (Wajood Ibn-e-Sadaf). The scene is immediately captured by Jaffar, whose character looks at both the horrors of war and tales of his childhood. The usage of the phrase freedom and democracy across the three plays is calculated, and is part of the dark irony surrounding war, and how insignificant it is in the face of violence.

The interrogation room becomes the setting for the third and final play, titled Crimes and Punishment. Khoosat plays an American soldier who interrogates an Arab woman (Bucha) who has fought for democracy, but is now confronted by the realities of the invasion of her country, along with the deposition of a dictator. With Bucha grieving the loss of her son and husband, both go to the brink of their talent. This is demonstrated through an avant-garde style of presentation, in which Khoosat uses a live camera on a projector during the scene.

Bringing Ravenhill to Pakistan will turn heads with the traditional theatre going audience, but it is a very important play for our society. Maintaining the essence provides an important look at the hegemonic dimensions of ideology which in the end, is very relevant to Pakistan.

Published in The Express Tribune, April 8th, 2014.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

1725612926-0/Tribune-Pic-(8)1725612926-0-165x106.webp)

1725254039-0/Untitled-design-(24)1725254039-0-270x192.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ