Living legend: Rare Pashto music captivates audience

Concert was 10th in 'Instrumental Ecstasy' series which has gathered unique musicians.

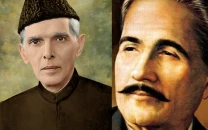

Umerzai has been playing the Sehtar for the last five decades. PHOTO: EXPRESS

It is late evening and Ustad Zainullah Jan Umerzai has just arrived in the capital, bringing along the traditional melodies of his native Charsadda. Clad in a woolen cap and wrapped in a thick khakhi shawl, the bearded maestro speaks to The Express Tribune about the history and origins of Sehtar, an instrument he has been playing for the last five decades. He is the last living legend to play the instrument.

The Sehtar from Charsadda is a long-necked lute played in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. While its name is believed to have been derived from the Setar, a Central Asian and Iranian long-necked lute, it is not related to the North Indian classical Sitar.

At the performance, Umerzai will play a combination of Pashto folk and classical tunes. “This music form has been propagated from Iran to Afghanistan and Pakistan,” explains the Institute for Preservation of Arts and Culture CEO Umair Jaffar, who has coordinated the performance at Kuch Khaas. The instrumental concert is the 10th in a series titled “Instrumental Ecstasy,” that has gathered rare musicians from all the provinces.

The maestro’s face lights up as he strums on the five-string instrument, which is different from the traditional Sitar in that the latter has only three chords. Next to Umerzai, Ustad Malang Jan creates rhythm on Mangai (clay percussion) to complement the melody. Playing in unison, they seem at ease with each other and one does not need lyrics to experience the subtle yet spellbinding Pashto beats. Mangai has been historically played at mujrahs, the one that Malang plays is covered in plastic.

The ancient music form continues to be played at various celebratory occasions. Some popular tunes on Umerzai’s playlist include Bibi Shireen, Larsha Pikhawar Ta and Attan. “My music can make sad people happy and happy people dance,” the maestro claims, clutching his wooden instrument with pride. “It can move lovers and travelers to tears,” he adds.

Talking about the appreciation he has garnered for the music, Umerzai says “People in Pakistan do not value poets and musicians as much as those do in Afghanistan and India. While the Pakistanis enjoy the music that we make, they do not warm up to it as much,” he complains.

He also rendered snippets of devotional music. Umerzai has also played background scores for a large number of Pashto films and also composed his own songs.

As a young boy, he would listen to the regional radio and has drawn inspiration from the poetry of the Sufi saint Shah Mahmood of Afghanistan.

Published in The Express Tribune, December 1st, 2013.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ