Legends of Lahore

Welcome to a city steeped in history, where every street has a story to tell…

With a history that stretches back to the days of the Ramayana, Lahore — thanks to its strategic location — has passed through many conquering hands. As the last major stop on the road to Delhi, this much conquered city has always been a convenient stop for pillaging armies looking to loot and resupply before moving on. Many a times, Lahore has itself been the ultimate target. As a result, Lahore has been mercilessly plundered, torched and razed to the ground several times. But no matter how many times it has been destroyed, this city of mine has always risen Phoenix-like from the ashes — stronger than ever before.

That because, at its heart, Lahore is a survivor. All of its bittersweet history is there to be seen in its tombs, mosques, palaces, fortresses, museums and gardens. It has seen ages of war and devastation, as well as periods of cultural, intellectual, musical, literary and humanistic evolution. It remains a city of vivid differences and haunting nuances; where bustling bazaars, frenzied streets, fading elegance and assorted architecture merge into a history that is both dramatic and fascinating. For those who know how to listen, every place in Lahore — from the most monumental structure to the most ordinary street — has a story to tell.

The Mosque That Should Not Be There

Next time you visit the newly constructed food street, opt to get a bird’s eye view by choosing to eat at one of the rooftop restaurants. Then, when you look down at the breathtaking view of the iconic Badshahi Mosque in all its splendour, just pause to consider that it was never even supposed to exist! So where did the Badshahi Mosque come from, you ask? Well herein lies the first of the tales we have to tell…

Hark back to a time when Emperor Shah Jehan’s son Dara Shikoh was prince of Lahore. Famed for his devotion to Sufi saint Hazrat Mian Mir, Dara decided to honour the saint by building a path from the Akbari gate to the saint’s shrine in Taslimpur (near modern-day cantt). Ordinary bricks simply wouldn’t do for this purpose and so Dara Shikoh imported red sandstone tiles all the way from Jaipur. But no sooner had the bricks arrived that his brother Aurangzeb killed him, while imprisoning his father Shah Jehan. Having settled matters of succession in this fratricidal fashion, Aurangzeb took one look at the massive pile of bricks and decided that, instead of a pathway, he would build a mosque fit for an emperor. Had Aurangzeb lost that struggle, and had Dara Shikoh built his pathway, Lahore’s entire urban structure would be completely different! And you, while sitting at that rooftop restaurant, would be staring down at a very different city.

Scaling The Mountain Of Light

Right outside the mosque that shouldn’t exist, in the midst of the Hazuri Bagh, stands a pretty marble pavilion. Beyond being known as the Sikh Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s baradari, it doesn’t usually evoke much interest among passersby. After all, it stands in the shadow of the Badshahi Mosque. But this pavilion was constructed to celebrate the acquisition of the world-famed Koh-i-Noor diamond which, according to ancient Sanskrit scriptures, brings misfortune upon its possessor, unless the bearer is either God or a woman. The way in which this diamond came into the Maharaja’s hands, and led to the building of the baradari, is the tale we will now tell.

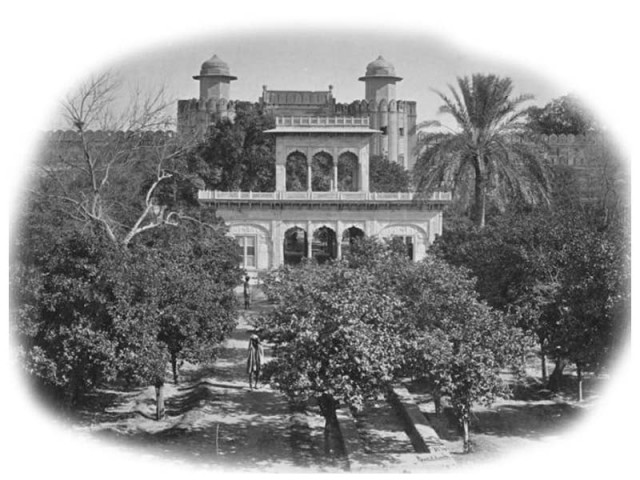

Before it became Ranjit Singh’s possession, the Koh-i-Noor was the greatest treasure of the Afghan King Shah Shuja. When he was overthrown by his brother Shah Mehmud, he fled and took refuge in Lahore, seeking the assistance of Ranjit Singh in order to reclaim his lost kingdom. The astute Maharaja agreed on the condition that the Koh-i-Noor be handed over to him. Shah Shuja was duly placed in the state guest house, the Mubarak Haveli, and carefully watched. Day after day, negotiations were carried out and envoys sent over to obtain the diamond. When all efforts failed and the Maharaja’s patience began to wear thin, Shah Shuja finally agreed to hand over the diamond on the condition that Ranjit Singh come and take it from him in person. The meeting ensued and Shah Shuja had no choice but to make good his promise. After a long silence, he finally handed over the Koh-i-Noor with a heavy heart. The victorious Maharaja held it in his hands, inspected it with a gleam in his eyes and asked Shah Shuja as to what was the price of the diamond. Centuries ago, the Mughal King Babur had estimated its value as being equal to half the daily expenses of the world. It was this question that Ranjit Singh asked of the disposed Shuja: “What is the Koh-i-Noor worth?”

To the Maharaja’s surprise, he answered: ‘A laathi’ (a cane). Taken aback, the Maharaja asked Shuja what he meant and he replied: “You are taking this diamond from me by the force of a laathi (forcefully). Know that there will come a power after me which will take the diamond from you through the force of a laathi as well.”

Having given this bold answer to none other than Ranjit Singh himself, and having now given him what he wanted, the dethroned king feared for his life. Conspiring with the guards at the Mubarak Haveli, he escaped by breaking a hole in the wall one night. But to his dismay, the bribed security guards at the gate he was supposed to escape from had been changed overnight, thus ruining the plan he and his co-conspirators had hatched.

Shuja was left with no choice but to escape from the malodorous Mori Gate, which served as the drain for all the city’s waste and sewage. He emerged spluttering on the other side, covered from head to toe in the excrement of Lahore. From there he went to Data Darbar, where he took a welcome bath and found a change of clothes. Before making good his escape, he stared back at the city where he had been deprived of his greatest possession and said:

Lahori, lush push bohti, mohabbat thori; vikhavan booa, langawan mori

(Lahoris, big on promises, short on sincerity, will promise the door but make you pass through a hole)

Later, his comments about the laathi were to prove prophetic as the Koh-i-Noor fell into the hands of another set of conquerors: the British.

For all its brilliance, the diamond was a very small part of the treasure looted from Ranjit Singh’s Toshakhana by the British when they took over Punjab. Few know that the ‘Coronation Necklace’ which traditionally adorns the Queen of England’s neckline was made from jewels taken from Lahore. At 161 carat, it stood as the world’s most expensive necklace when made for Queen Victoria in 1856. Its main pendant stone, at 22.5 carats, is still known as the ‘Lahore Diamond’. Also made for the Queen were earrings from the Timur Ruby necklace which was also taken from the Lahore Durbar. To date, the list of the entire treasure is kept in a secret manual by jewellers of the royal family and its contents are not shared with anyone. Estimating its extent is a monumental task but historian Carl Steinbeck, while taking stock of it, wrote that ‘it was doubtful whether any royal family in Europe had so many jewels as the court of Lahore’. So whenever the Queen of United Kingdom steps out in her bejewelled majesty, you can afford a private grin for you now know exactly where her royal jewellery came from.

A Defeated King, A funeral pyre, A tree that stands no more.

Then there are those tales that have no landmarks to pay them mute testimony; that are remembered only distantly, if at all. One such tale is that of Raja Jaipal.

The next time you find yourself between Bhaati Gate and Mori Gate on the circular road, transport yourself over a thousand years into the past and imagine a scene of despair and defeat. There stood the Hindushahi King Raja Jaipal, in full military regalia. Hiding great shame and sorrow behind a stoic face, he lit a pyre and climbed onto it, immolating himself in full view of a crowd of onlookers. This was Jauhar, an act of self-immolation usually committed by the women of the martial Rajputs in order to avoid the shame of being captured by an invading army. What drove a king to do such a thing? The answer is: defeat. This proud king had fought war after war against the Afghan invader Subuktagin, only to suffer incredible losses every time. Even the death of his great rival did not deliver him, as on November 27, 1001, Jaipal was thoroughly beaten by Subuktagin’s son, Mahmud of Ghazni. Though he won his freedom after paying a huge ransom, this proud Punjabi king could not bear the loss and ended his life on a flaming pyre. Until not too long ago, there stood a Pipal tree at the spot that was known as the Jauhar tree. Did those who had sheltered beneath its branches know the sacrifice it marked?

The Tale of Sadhu, the Thief

Not all of the landmarks of Lahore speak of lost treasures and long-dead kings. Some stories speak more to the soul of the people of this city. Let us now walk to the heart of the Macchi Hatta Bazaar in the Mochi Gate area; to a long-dry well known only as Sadhu Chor’s Well. In the eighteenth century, during the decline of the Mughal Empire, Lahore was ruled through proxy by the Afghan king Ahmed Shah Durrani. Lahore, which has never been short of colourful characters, was also home to one popularly known as Sadhi Chor (Sadhu the thief). So notorious were his ways that he was the first suspect for any unexplained theft in the entire city. There was this one particular pakora shop, the fried delicacies of which caught his fancy. Once hooked, Sadhu started regularly stealing food from that shop. The shop owner would complain to the authorities, Sadhu would be arrested, punished and subsequently released. That, however, would not deter him from stealing from the poor man’s shop once again. Then one day Sadhu found the shop owner closing down the shop. Distressed, Sadhu asked him what had happened, to which the shopkeeper replied: “I have enough of you! You have rendered me penniless with all your thievery and so I’m closing down my business.” So moved was Sadhu that, true to his colourful ways, he asked the shop owner to hold off on his decision and wait for him at his shop. After a few hours, the shop owner found Sadhu approaching him holding two huge bags. He handed over the bags to the shop owner and told him: ‘Today I’ve compensated you for all that I’ve made you suffer for; our balance is clear.’ Speaking thus, Sadhu vanished into the dark of the night.

Opening the bags, the shop owner was astonished to see them full of jewellery and precious stones worth hundreds of thousands of rupees! The next day, he awoke to find the city in an uproar; there had been a heist the previous night at the house of none other than the resident ruler of Lahore, Nawab Zakriya Khan. As expected, all evidence pointed towards the master thief Sadhu, who was subsequently arrested and sentenced to death by hanging. After all, committing a petty crime at a pakora shop was different from robbing the resident ruler’s palace.

The day of execution arrived and Sadhu was led through the streets in a procession that led to Mochi Gate, at the very place where the Urdu Bazaar now stands. A huge crowd gathered to witness the hanging of this colourful yet notorious character of Lahore. While being led through the crowd, Sadhu saw a familiar face. It was the shop owner, holding the bags of valuables in his hands. He gestured to Sadhu, indicating that he would return the loot so that Sadhu’s life could be spared. Pretending not to see him, Sadhu, responded by making a speech saying: “Whichever one of you is in possession of the booty should keep it to himself for I will not be spared even if you return it to the authorities. I have but one request to make: After I die, build temples and wells in my name so people can bless me and I can earn some reward in the next life.”

After his hanging, the shop owner duly had temples and wells built in various parts of Lahore to honour the memory of the master thief with a heart of gold. Unfortunately, all that exists out of these many monuments is the single dysfunctional well in Macchi Hatta Bazaar. It was years ago that I last saw it and perhaps it too has fallen prey to the vagaries of development and growth. I wish that all the wells and temples attributed to him weren’t demolished for they not only would have kept Sadhu’s name alive but made Lahore’s story so much more charming.

These are but a few of the legends of Lahore. Tales that yet remain untold are of the myths surrounding Dina Nath’s well outside Wazir Khan Mosque. Then there’s Aitchison College itself — the original location of which was intended to be in Shahdara. From the controversy behind the Sunehri Mosque, to the legends of the Ravi and the fables of Lahore Fort’s secret tunnels — the tales of Lahore are endless. Having seen so many ups and downs during its existence, Lahore is a whole world unto itself, where the past and the present exist at once. Its legacy includes the Hindu, Mughal, Persian, Afghan, Sikh and British. Its chroniclers range from Ptolemy to Al-Beruni and Kipling. Its forts and gardens have seen festivals and famines alike, and at times, relating its tales is simply an unbearable task as one story spins into the next, as history melds into myth and legend.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, October 28th, 2012.

Like Express Tribune Magazine on Facebook and follow at @ETribuneMag

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ