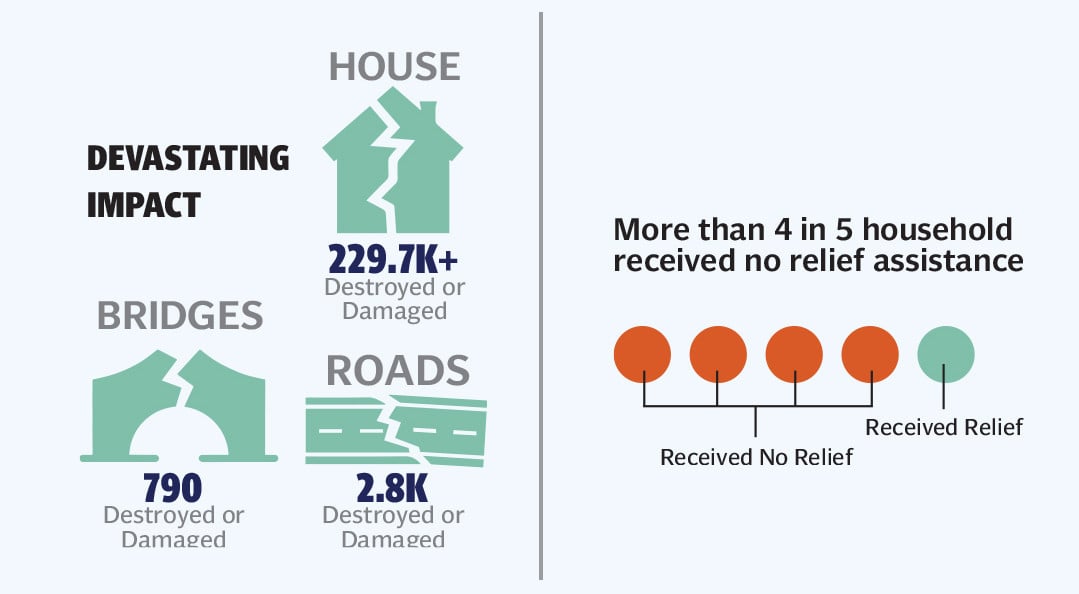

In the sweltering aftermath of Pakistan's most devastating monsoon season in recent memory, the waters have receded, but the scars remain etched deep into the lives of the nation's most vulnerable. The 2025 crisis unfolded with ferocious intensity. Torrential rains, swollen by climate change-fuelled anomalies, unleashed flash floods and accelerated glacial outbursts across Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), Punjab, and Sindh provinces. By mid-October, the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) reported over 1,037 deaths and 6.9 million affected nationwide, with 3 million forced from their homes. The flood also caused extensive damage to infrastructure, with over 229,700 houses, 790 bridges, and 2,811 kilometres of roads destroyed or damaged according to NDMA.

The impact on minorities

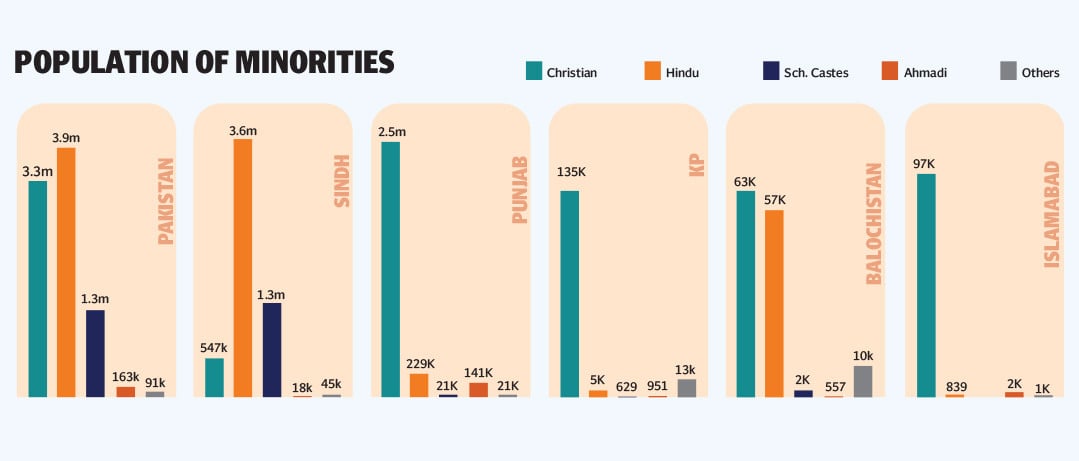

A direct correlation exists between the specific provincial epicentres of the floods and the primary geographic concentrations of Pakistan's Christian, Hindu, and Sikh communities.

The Christian population is heavily concentrated in the flood affected areas of Punjab e.g. Lahore, Sialkot (Nala Aik, Nala Daik, Nala Palko) and Kasur (Bhikkiwind). This geographic vulnerability is compounded by socio-economic factors. A significant portion of the urban Christian population resides in katchi abadis that are often built on marginal, flood-prone land such as riverbanks and lack state-provided drainage or sanitation, making them exceptionally vulnerable to the urban and riverine flooding seen in 2025. Furthermore, Christians largely belong to the sanitation worker class, a role that exposes them directly to the hazardous after-effects of overflowing sewers and stagnant floodwaters.

"Tribal Hindu communities in interior Sindh" were explicitly identified in relief reports as being "particularly affected". The floods in Sindh mapped directly onto districts concentrated with Hindu population including Thatta, Badin, Jamshoro, Dadu, Umerkot and Tharparker. The latter two have the highest absolute numbers, with Tharparkar at 810,000 population and Umerkot having 54.7% of Hindus in Pakistan. Located in an arid region, these are identified by the NDMA as a "severe" risk zone for drought. Their primary vulnerability, is socio-economic. The Hindu community is disproportionately affected by the hari and bonded labour system. As a landless minority often trapped in debt, their ability to evacuate or access aid is severely compromised.

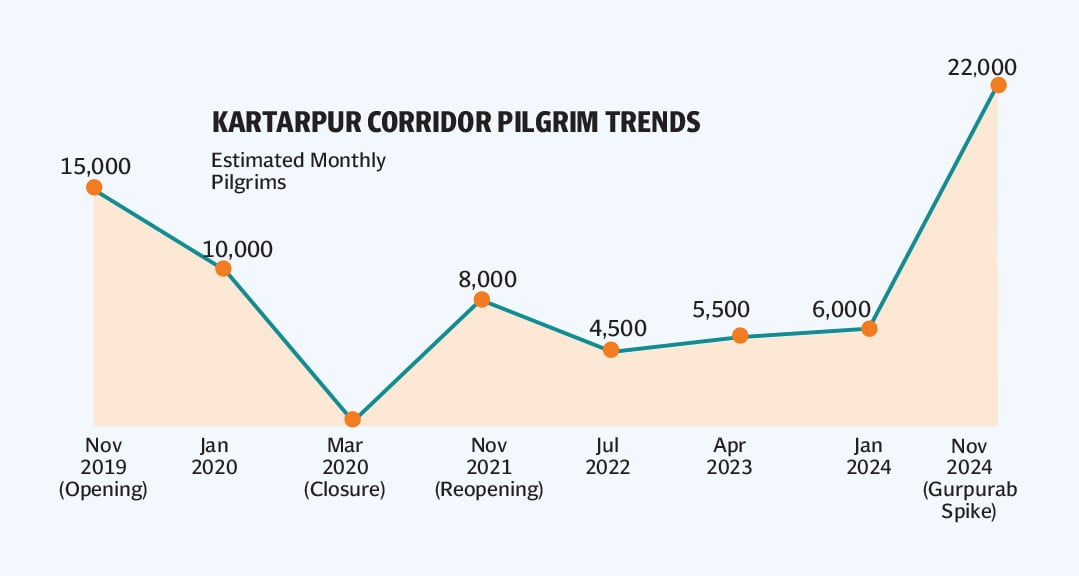

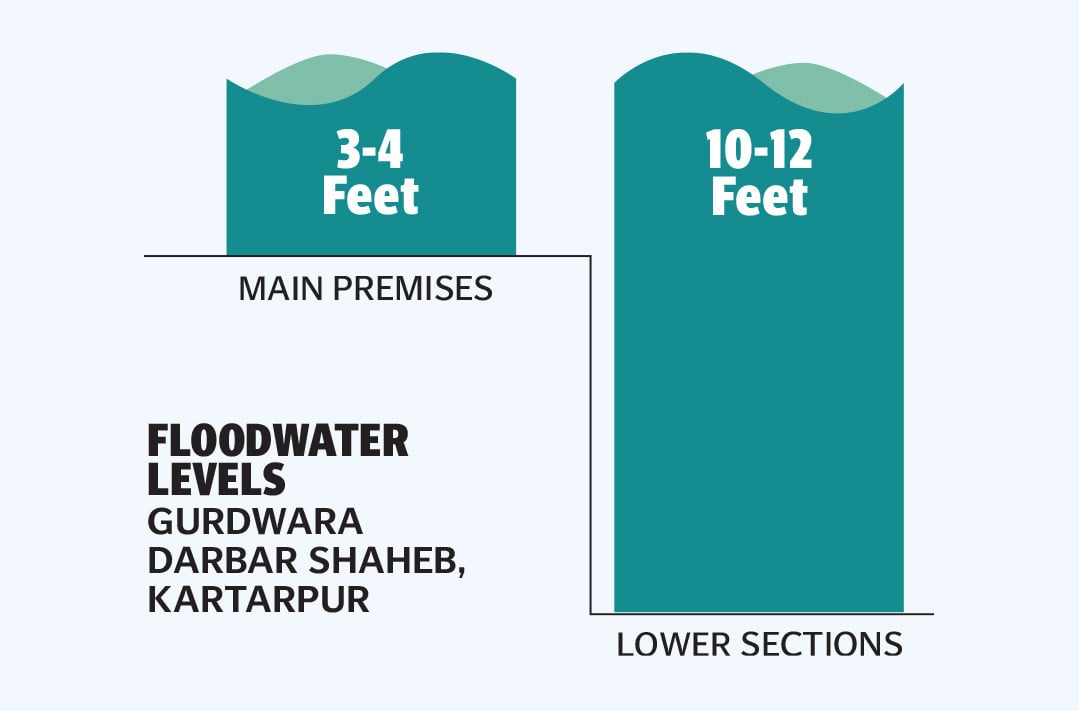

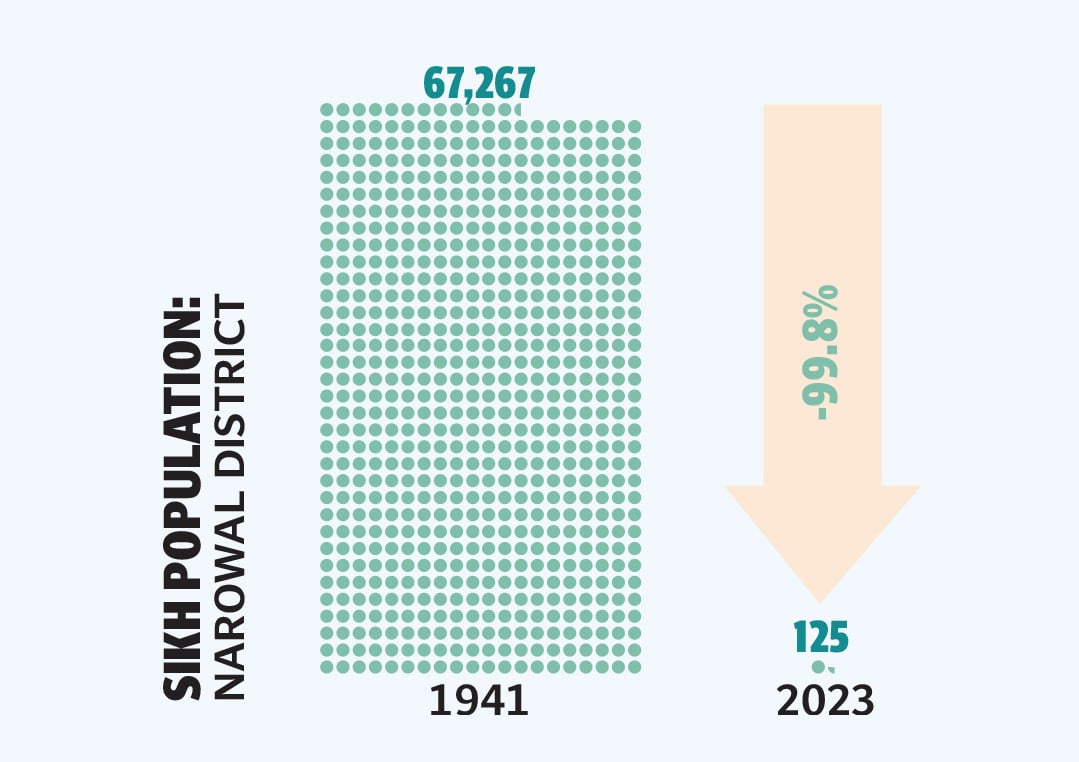

The Sikh population is small, estimated to be 16,000–30,000, and highly clustered in a few specific locations including Buner district, KP, specifically in the village of Pir Baba which was directly in the path of the resulting flash floods and Narowal district, Punjab, home to the Kartarpur Sahib Gurdwara, and centre of the "exceptionally high" flooding from the Ravi, where floodwaters surged through the historic pilgrimage site, eroding foundations and submerging prayer halls. "According to the information received, several feet of water entered not only the main Darbar but also the entire complex of Sri Kartarpur Sahib,” says Giani Kuldip Singh Gargajj, acting Jathedar of Sri Akal Takht Sahib, in an urgent statement that rippled panic through global Sikh networks.

Neglected in aid relief

Field Marshal Syed Asim Munir, Pakistan’s Army Staff, visited the area in late August, promising swift restoration. “Protection of minorities and their religious places is the responsibility of the state and its institutions,” he assured during an aerial survey reported by the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR).

Yet, amid the widespread tragedy, ethnic and religious minorities like Sikhs, Hindus, Christians, and indigenous groups in flood-prone regions, bear a disproportionate burden, their pleas for aid often drowned out by the roar of indifferent bureaucracy and societal prejudice. A September 2025 national survey by Gallup Pakistan found that over 80% of all affected households received no relief assistance whatsoever.

This data is crucial because Pakistan's religious minorities are disproportionately represented among the nation's poor, landless, and marginalised. The Gallup poll proves that the very system they were relying on was, by default, failing the demographic they belong to. In 2025, the HRCP issued a statement, reiterating its previous reports and calls to action, identifying the floods as manmade, due to poor planning, corruption, and land grabs and demanded that relief efforts provide "equitable access" for "the most vulnerable". Read alongside the 2025 Gallup data and the historical reports of discrimination, their demand functions as an indictment of a system that is, by default, failing to provide that equity.

Qualitative reports from 2025 confirm that "marginaliSed groups, including minorities" faced reduced access to support, raising "risks of favouritism and tension in aid distribution".

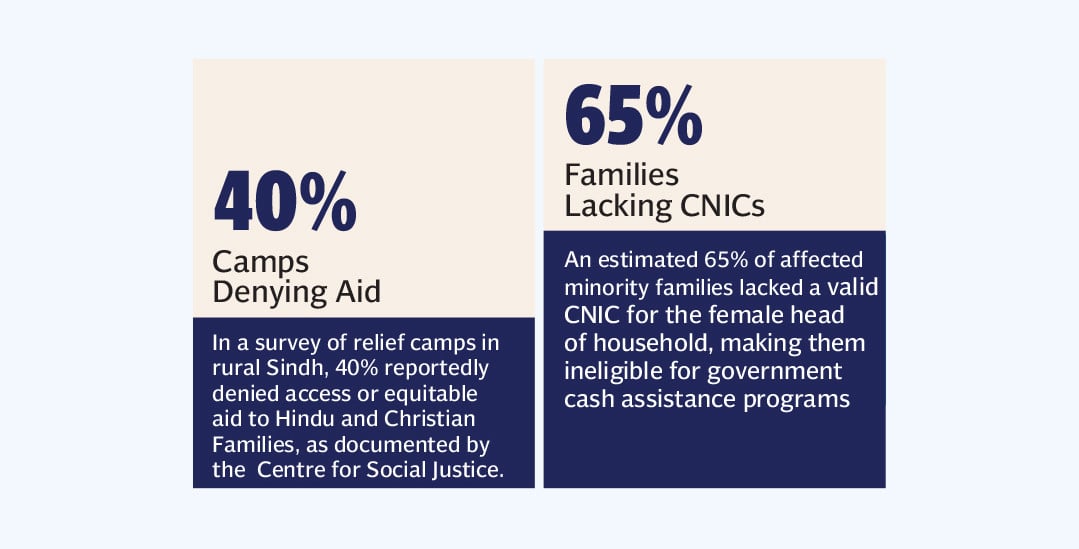

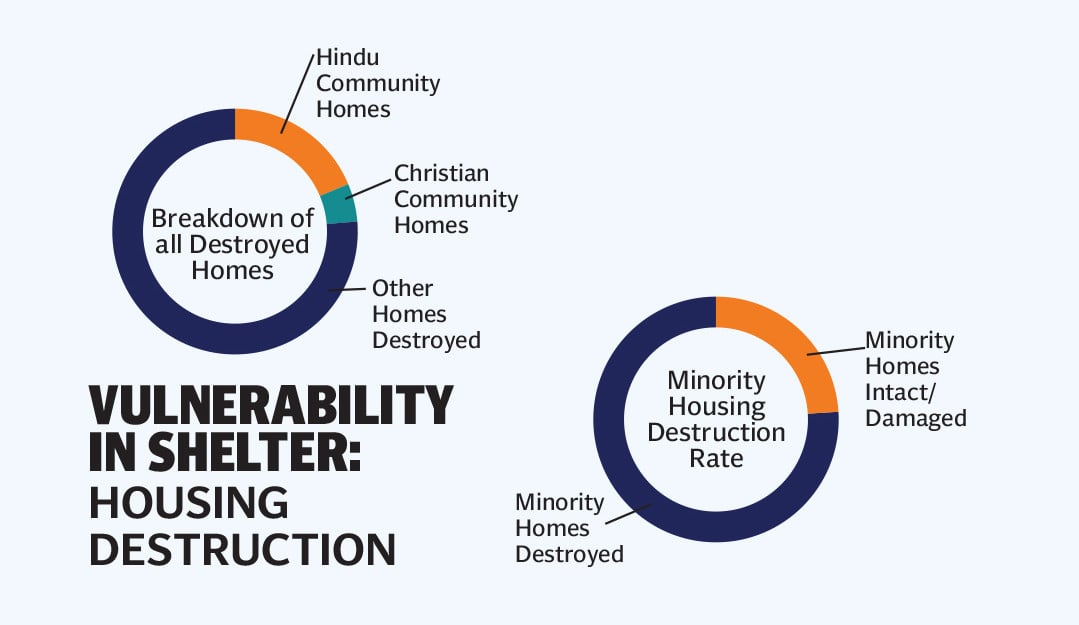

This data validates long-standing, documented patterns of discrimination in aid distribution during past floods, confirming that these communities face a compounded vulnerability: they are geographically marginalised into the most disaster-prone regions and systemically overlooked in the relief and recovery phases.

Relief efforts, coordinated by the NDMA and international partners like Unicef and Care, have reached millions amid the chaos, but structural barriers such as delayed surveys, remote access, unchecked profiteers, leave minority enclaves in Punjab and Sindh underserved. As Dr Andaleeb Koasar Jhatial, lecturer at the International Islamic University Islamabad, warns at a roundtable on humanitarian challenges, “Floods and climatic shocks disproportionately affect women, children, and minorities,” with provincial funding tussles and hoarding cartels spiking staples 30-50%. In Nankana Sahib and Thatta, aid rolls unevenly: "relief supplies... seem insufficient," with displaced families reporting delays and inadequate rations, as detailed in Shamsul Islam Khan's, former vice president of the Karachi Chamber of Commerce and Industry and commodities expert, on-the-ground assessment prompting interfaith groups to bridge gaps. “We prioritise humanity above all else,” says Mahinderpal Singh in an online platform’s story on flood relief coalitions, whose teams clean sacred sites while the state catches up. For survivors in leaking Punjab tents, it's a cruel wait: profiteers exploit the flood, turning tragedy into "a test of... social justice," as the vice president frames the unfolding crisis.

This pattern of neglect is starkly evident in Sindh's Thatta and Badin districts, where Hindu and Christian fishing communities, comprising about 5% of the province's population, saw their thatched homes and boats obliterated. “We have lost everything, our home and belongings. The greatest worry is what will happen after the water recedes and we have to leave this camp? Where will we go,” says Rubina Bibi to an international news site from a submerged village, her family now crammed into a relief tent riddled with fever and fear. Her story, like thousands of others, now huddles in makeshift tents, battling outbreaks of malaria, dengue, and skin infections exacerbated by stagnant floodwaters. Women and girls, already facing heightened risks of gender-based violence in cramped camps, report being overlooked in aid distributions, their pleas dismissed as "less urgent."

Human rights advocates paint a grim picture. The International Service for Human Rights (ISHR) warns that religious minorities are "often the last to receive aid," heightening vulnerabilities to exploitation and disease. In KP, Kalash and other indigenous groups in Chitral valley, non-Muslim ethnic minorities clinging to ancient traditions, faced glacial lake outburst floods that wiped out terraced farms and sacred groves. "The floods have washed away our ancient way of life, leaving us to rebuild what little remains of our heritage," laments a Kalash community spokesperson in a plea covered by a daily, speaking amid calls for government intervention to save their eroding culture. With limited access to early warning systems, these remote communities were more at-risk of sustaining casualties than those in nearby Pashtun-majority villages.

The impact on children

The floods' toll on children, who make up a third of Pakistan's population, is particularly harrowing for minorities. Unicef] reports 255 child deaths by early September, many from drowning or post-flood illnesses In minority-heavy areas, disrupted schooling, with over 1,000 schools damaged, threatens generational erasure of cultural identities. “In this tent school and safe space, we found so many things to learn and play as the kind teachers make us smile. It is a very good place to come and forget our grief and pain,” shares Iqbal, a 9-year-old student displaced from his flooded home, in a Save the Children press release on emergency education efforts, his words a fragile thread holding onto normalcy amid the ruins.

Economic impact

Economically, the blow is existential. Minorities, often relegated to informal sectors like brickmaking and agriculture, lost livelihoods without the social safety nets afforded to others. An estimated 1.2 million hectares of land were inundated in Punjab, which serves as "Pakistan's food basket". Care International notes that damaged infrastructure has isolated these groups, delaying cash transfers and microloans essential for rebuilding. A CGAP study highlights how climate shocks like these erode financial inclusion gains, pushing the poorest and disproportionately affected minorities, deeper into debt traps. With Rs 500 billion in agricultural damages alone and profiteers jacking up prices, rural producers, 40% of the workforce, face famine risks, their fields and livestock swallowed by the flood.

The most insidious impact of the floods on the Hindu community relates to the system of bonded labour.

Critics point fingers at governance failures. Poorly maintained embankments and unplanned urbanisation along riverbanks amplified the disaster, as seen in the 2022 floods' eerie redux. “We cannot allow our people to bear the brunt of climate inaction,” argues Senator Sherry Rehman, Federal Minister for Climate Change, in an op-ed on monsoon vulnerabilities, calling for equitable international aid. The UN has stepped in with emergency plans, but gaps persist as OCHA notes uneven distribution, with minority areas underserved.

As Pakistan tackles reconstruction, voices from the margins grow louder. In relief camps dotting Punjab's floodplains, interfaith coalitions are emerging, blending Sikh langars with Christian prayer circles to share scarce resources. “We learned the value of humanity from Guru Nanak. His message inspires us, and we try to follow his example by putting humanity first in everything we do,” says Mahinderpal Singh, manager of United Sikhs in Pakistan, in a web story about the teams that doled out aid regardless of faith.

The policy omission

Yet, without targeted policies, bolstered early warnings, minority-inclusive disaster planning, and culturally sensitive aid, the 2025 floods could create deeper divides. In a nation where minorities number over 4 million, ignoring their plight isn't just unjust; it's a flood waiting to happen again. We must embed equity into our disaster frameworks, drawing from the National Disaster Risk Reduction Strategy (NDRRS) 2025–2030 and the International Organisation for Migration's (IOM) Pakistan Crisis Response Plan 2023–2025. Yet, an analysis of the NDRRS reveals a critical policy omission: while it references the need for inclusion and mentions "marginalised communities," it fails to explicitly define "religious minorities" as a vulnerable category, risking perpetuation of exclusionary practices during multi-year recovery phases and locking these groups into persistent dependence amid future shocks.

The failure to translate the high-level policy into the operational guidelines creates a "policy vacuum." The PDMA and DDMA authorities, who rely on operational guidelines, have no official mandate to collect pre-disaster data on minorities, assess their specific vulnerabilities (e.g., landlessness, housing type), or train response teams to handle caste or religious discrimination. This omission provides systemic cover for local-level discrimination. This exact chain of failure was documented in 2010 with the Ahmadiyya community and repeated, unaddressed, in 2022 with Scheduled Caste Hindus, proving it is a feature, not a bug, of the current system.

This gap is mirrored in the National Climate Change Policy (2021) which acknowledges that "vulnerable poor and minority groups" face increased risk, but the subsequent National Adaptation Plan implementation framework contains no specific, actionable initiatives for religious or caste-based minorities, subsuming them invisibly under "social inclusion". At the provincial level, there is a total disconnect between policy and reality. In Sindh, the PDMA's generic policies resulted in an "inadequate" and "unsatisfactory" response for minorities, necessitating a separate investigation by the Sindh Human Rights Commission (SHRC). In Balochistan, the 2022 Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) found "substantial perceived favoritism, nepotism, corruption... discrimination, and exclusion in aid distribution," which "deprives marginalised and excluded communities of support".

The state's primary mechanism for aid delivery is cash transfers (e.g., via BISP) contingent on a valid CNIC from Nadra. This system, while promoted for transparency, is a well-documented tool of exclusion. The NDMA itself acknowledges the "difficulty in access to assistance for undocumented persons (CNIC...)". This system disproportionately excludes the most marginalised, particularly women in rural areas not registered as "heads of household" and other undocumented minority community members.

This on-the-ground reality, documented by human rights groups, was corroborated by the government's own high-level assessments. The government-led Pakistan Floods 2022: Post-Disaster Needs Assessment, with support from the UN, World Bank, and European Union, makes several critical admissions:

- The recovery strategy must be "inclusive of marginalised groups, including women, persons with disabilities, and religious minorities".

- The PDNA explicitly lists "religious minorities" as among the "social groups facing discrimination and lack of access to relief".

- The livelihood recovery strategy must include "participation and fair wages to members of marginalised and minority communities".

This creates the final, damning contradiction: the problem of discrimination was acknowledged in high-level planning documents in Islamabad, while the NCHR's on-the-ground investigation in Sindh found "No specific measures" were ever implemented. This gap proves the ultimate governance failure: even when the problem is identified, the implementation and accountability mechanisms to stop it at the district level are non-existent.

To address these issues, we must develop multilingual early-warning systems that integrate indigenous knowledge, such as expanding the PDMA Madadgar app for real-time alerts in languages like Punjabi, Sindhi, and Kalasha, with geo-tagged vulnerability assessments ensuring 80% coverage in high-risk minority districts like Narowal and Chitral. This protocol, mandated under NDRRS, could slash fatalities by 30–50% among flood migrants, as modelled by IOM, by partnering with NGOs for community-led dissemination via radio and SMS. Complementing this, institutionalising gender and equity audits in disaster risk reduction (DRR) plans, requiring 30% minority representation in local committees, would foster participatory assessments, forming inclusive DRR bodies through community-based organisations like United Sikhs and piloting community-based adaptation in ethnic enclaves, as outlined in NDRRS sections on social inclusion and IOM's protection mainstreaming guidelines, while explicitly amending the strategy to define religious minorities as vulnerable, closing the identified gap in Sections 10.4 and 13.6.

Transitioning from prevention to response, mainstreaming culturally sensitive aid protocols demands allocating 20% of relief budgets for minority-specific needs, such as repairing temples and gurdwaras alongside faith-sensitive shelters that prevent gender-based violence and trafficking in camps. NDMA-led training modules on cultural competencies for responders, coupled with cash-for-work programmes prioritising informal minority labourers, align with IOM's emphasis on GBV case management and civil documentation, while NDRRS calls for psychosocial support tailored to marginalised groups. For recovery and rehabilitation, shock-responsive social protection must integrate DRR into safety nets like Benazir Income Support Programme expansions, offering microinsurance subsidies and livelihood restoration linked to cultural heritage, such as rebuilding Kalash terraced farms, through community-driven quick-impact projects for resilient shelters. Although, mandate that possession of a CNIC cannot be the sole prerequisite for life-saving aid (shelter, food, water, and emergency medical care), as recommended by previous analyses. Alternative identification, such as UN or INGO registration, or verified community-vouching systems, must be officially sanctioned. International donors should recognise that mainstream channels are failing. A significant portion of recovery funds must be channelled directly to registered, local, and community-based organisations that have proven, long-standing access to and trust from marginalised groups who are "overlooked" by official channels. This builds on NDRRS's inclusive recovery pillars and IOM's targeting of 905,000 vulnerable individuals, including border minorities, with nature-based solutions to curb migration hotspots as urged by the International Water Management Institute.

Direct, unconditional cash grants should be provided for Sikh shop-owners in Pir Baba, Buner, to rebuild their commercial livelihoods. Funding for the provision of personal protective equipment and hazard pay should be approved for Christian sanitation workers tasked with cleaning hazardous flood-waste. Grants for the restoration of damaged religious sites, including the historic Hindu temple in Jamshoro and St James Parish in Sialkot. The link between flooding and the deepening of bonded labour must be treated as a human trafficking and slavery crisis. Humanitarian agencies must coordinate with human rights bodies to prioritise the physical extraction, debt relief, and legal protection of bonded labourers and their families from flood-affected feudal lands as a life-saving intervention.

Grant the National Commission for Human Rights nd the Sindh Human Rights Commission formal, independent oversight authority over all DDMA and PDMA relief operations, including the power to receive and adjudicate complaints of discrimination.

Finally, a robust monitoring and evaluation framework with disaggregated data on minority outcomes, alongside capacity-building for 10,000 responders through cross-sector workshops with faith leaders, would ensure accountability via annual equity audits and nationwide scaling of apps like Madadgar. NDRRS mandates such gender-disaggregated indicators and training, echoed in Human Rights Watch's calls for monitoring to avert displacement and a Frontiers in Communication study on AI/IoT for inclusive alerts. With an estimated $500 million investment, these protocols, cemented in NDMA's annual plans, could transform Pakistan's response from reactive chaos to equitable resilience, honouring the survivors' unyielding call for justice.

The writer is a human rights expert, filmmaker & researcher and can be reached at qashif.mirza@gmail.com and (X) @qashifmirza

All facts and information are the sole responsibility of the writer