Lame is the new cool

The Sarri-alist Movement (TSM) — is popular Facebook page that hosts sarris, lame jokes, and memes.

‘How did the cow get out of the well?

Bohat mushkil se.’

If you rolled your eyes at the above joke, it’s okay. Because lame is the new cool.

This is what the massive popularity of The Sarri-alist Movement (TSM) — an extremely popular Facebook page that hosts sarris, lame jokes, and memes — will convince you of.

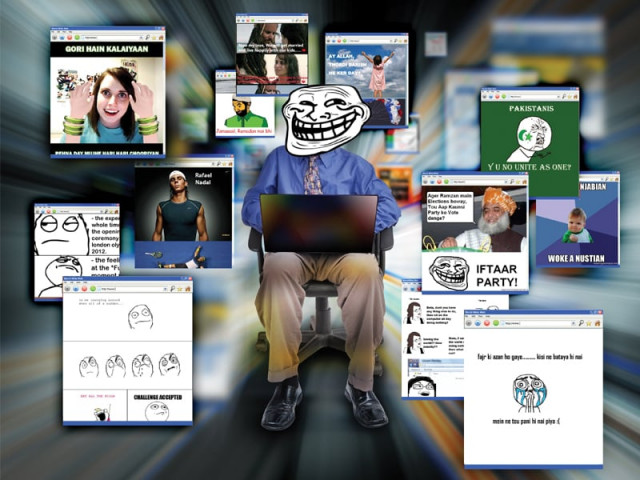

In popular usage, an Internet meme is a concept in the form of text, image or video that spreads, often virally, on the Internet. You have almost certainly seen them, from Lolcat to Aunty Acid, if you have a Facebook account.

And from the locally created Facebook pages, your friends have been posting, and reposting, memes from the massively popular Sarcasmistan (71,000 likes), TSM (42,000 likes) and Ziada English Na Jhar Eminem Ki Olaad (186,000 likes) and others.

Globally, memes have been around since the late 1990s but in Pakistan the growth of this pop culture movement has gained critical mass only in the last year. The TSM was a page started by five college students, Zain Khalid Butt, Hamza Aamir, Omar Nawaz, Bilal Afzal and Qasim Ahsan, from the Lahore School of Economics (LSE).

In the course of this project, they have had to deal with issues from hacking to moderating often vicious online debates, and were even offered jobs. The idea was to produce and share ‘sarris’- extremely lame jokes — so as to “take the sarri-al culture to new heights.”

We talked to three of the founding members, Zain, Hamza and Qasim, about TSM and the increasingly popular meme culture of Pakistan.

Q. How did you come up with the idea of the movement?

Zain: The word ‘sarri’ means a lame joke, and when we were in Aitchison, we used to crack lame jokes all the time. In fact, we had quite a following for it. The idea came to us while we were in LSE. At first, we wanted to start a school magazine called LS-Sarri, but there were far too many inconveniences: time, printing and not to mention permissions. Hence, we settled on the idea of a Facebook page instead.

Q. How did memes start on TSM?

Qasim: A sarri is something that is funny because it’s ‘unfunny’. For example: ‘George Clooney ke bhai ka kya naam hae? Nishaat Clooney’. A meme is an idea that spreads to a point where it is readily recognised. As such, sarris can be memes and memes can be sarris, but they aren’t the same thing.

Hamza: Personally, I think memes ruined our page. Given the option, I would wipe them off the face of the earth. The whole idea of the page was [to have] single-line textual jokes, that people would sometimes copy off from text messages; they would hang around for thirty minutes or so, watch other people ‘like’ their posts, count the number of girls that liked their post, and so on. But then, some users realised that pictures were more visible to visitors. They added captions and eventually started using these rage-faces (figures and faces conveying specific emotions) to create comic strips. An inherent flaw in this whole system was that people could, and regularly would, copy content off of websites like 9gag and 4chan, and we hated that. If we found users plagiarising, we would ban them from the page. However, if something was genuinely funny, even if it were a meme, we would endorse it.

Q. A lot of memes now have a local touch to them. How would you describe the integration of something that was foreign to our culture and has now become so recognisable locally?

Zain: I would say that the whole meme culture started from The Sarri-alist Movement. We think most people who came to the page did not know about memes before. We built up a large user base and eventually people had their own opinions and points of views to share. The movement from captions to rage comics was easy because meme generators were easily available on the Internet. As the content on the page evolved, the rules of their usage also got recognised.

Q. Who generates these jokes and captioned images, and why are people interested?

Qasim: TSM is a very positive page because, in general, if you’re funny you’ll be accepted into it. This gives people an incentive to post on the page. And the page itself is an outlet to express yourself. Sometimes people just want to blow off some steam.

Zain: Recognition and ‘likes’, those are the major reasons why people upload things on the page. It’s the reason we made TSM in the first place. About 20 per cent of the people, most of whom joined us in the beginning, actually generate original content. But people who joined the movement later mostly plagiarised. Content themes are sensitive to real events, like after a cricket match you would see related posts for days. It’s like trends on Twitter.

Q. Do you think there may be any political or subversive trolling on the page to deviate its audience from the goal of humour?

Hamza: I would not say that there was much political motivation behind the posts because most of our generation is indifferent to politics. There would be pictures of politicians on it, even Quaid-e-Azam, but they would mostly be funny and pointless. There may very well be political groups, nationalist and anti-nationalists among the users but, considering the size of the user base, they’re quite difficult to track. Fortunately, the only fights we get are between school kids, and we sort of endorse them because they are funny!

Q. When and why would you say the page achieved critical mass? And how would you describe your user base?

Hamza: Critical mass happened last summer when we sat down day and night, focused on the movement, started marketing it and used our wits to make the page funny.

Zain: When we started, most of our users were students ranging from O levels to university first years so it’s 14- to 21-year-olds. Now the users start from 12 and I even have an uncle who’s 50. The reason people like it so much is because Facebook itself gets boring; there’s only so many people you can stalk on Facebook. Our page is dynamic, people keep posting new things and the rest keep soaking it up.

Qasim: There are certain regular members who are sometimes termed as ‘elites’, and who are in their thirties. Some of the most famous members of the page are recent university graduates.

Q. How do you deal with a user who is abusive or offensive?

Qasim: There isn’t any set way to deal with people who abuse the page and its members, and it depends on the severity of the infraction. Obviously, the worse we can do is to ban them, but you have to look at both sides of the picture. Usually what happens is that the TSM fan base takes it upon themselves to deal with troublemakers and they are almost always able to catch the user in the act and beat them to a pulp with witty, barbed wordings.

Q. So it appears that you were doing well … until the page got hacked. How and why did this happen? What now?

Zain: The page was hacked on the first of May this year by someone we had an argument with on the page. We weren’t expecting this to happen so we were not security conscious. Basically, a member of our team had his email address public, so the malicious user reset his password through his security questions. We tried everything to get it back, contacted Facebook, Hotmail, the government, but nothing happened. The hacker appointed new administrators to the page, and even though we got an offer to come back and work under him, we refused. We are making another page, although we would still want the old page back. We put in a lot of effort, it just doesn’t feel right. I had the option to have the page removed completely, but that would just put all the work to waste.

Qasim: It’s hard to know at this point who exactly is running the page because of the preference of the current admins to stay hidden. As such, I cannot answer this question with certainty. One reason that’s made me stick around personally is the incredible response the TSM fan-base gave when they heard the page was hacked and how passionately they defended our rights to own the page.

Q. With the page in the hands of someone else, what could they do with it? Do you think there is any power in controlling such a large forum? What have you gained from the experience?

Zain: The page has thousands of active young readers, and once we used it to advertise a charity event. To our surprise about 200 people showed up. We also sold t-shirts through it. I’m sure one could influence the users into doing a lot. As for us, I worked as a social marketer and I am currently working as a marketing executive because of the fame that came with starting this project. We have also received numerous job offers.

Hamza: TSM had a good run. I don’t think we want to replicate that after the hacking, and we now want to do something new. For now, we are looking ahead. We are planning new projects now; one of them is a video project.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, September 23rd, 2012.

Like Express Tribune Magazine on Facebook and follow at @ETribuneMag

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ