Breaking the cycle: Can Pakistan's tribal areas find lasting peace?

With attitude of both federal and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa govts unchanged, prospects for real improvement remain bleak

Another wave of displacement has hit the scenic Tirah Valley in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa’s Khyber tribal district amid talk of a limited offensive against the banned Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). This exodus marks yet another chapter in the tribal region’s tumultuous history, with locals caught in the crossfire and bearing the consequences of the ongoing blame game between the federal government and the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf-led provincial government.

Over the past two decades, the tribal areas and Malakand division have endured at least 12 large-scale counterterrorism operations, each promising to eradicate the Taliban threat. Yet the Taliban have only grown more sophisticated and brazen as the region remains mired in violence. The people of Tirah Valley in particular, and the rest of the tribal districts in general, are left to wonder: will this cycle of violence ever end?

The issue has become a point of political contention, with blame-shifting and point-scoring taking precedence over finding solutions. Locals are left to suffer — their homes destroyed, livelihoods ruined, and lives uprooted. Promised stability, reconstruction, rehabilitation, and institution-building have failed to materialise after every operation, as post-operation phases are neglected in favour of political engineering, re-engineering, and reverse engineering in Islamabad, Peshawar, Lahore, and Karachi.

As the government vows to annihilate militancy, echoes of past promises ring hollow. Will a new operation be different? Or will history repeat itself, leaving the people of Tirah Valley and the rest of the tribal districts to face another cycle of violence and displacement?

At this moment, locals find little reason to trust the government given the legacy of unfulfilled promises; yet they have once again vacated the area in the depths of a harsh winter, placing their faith in the state’s word once more.

These days, in both mainstream and social media, there is a growing trend of bashing Pashtuns from K-P in general, and the erstwhile Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) in particular.

Often out of context and accompanied by insinuations and stereotyping, this trend fosters alienation rather than integration, undermining the goals of the 2018 FATA merger. Authorities habitually shift blame for their own failures while using media as a key tool. Analysts and journalists unfamiliar with the basic ground realities of the tribal areas are deployed on media platforms to shape the national discourse, while key Pashtun stakeholders are kept entirely sidelined.

Some apolitical locals say that, instead of engaging them with mutual respect and an understanding of the complex local dynamics surrounding the prevailing threat, a media campaign was launched months ago on mainstream outlets portraying the entire Tirah Valley as a hub of drug cultivation, trafficking, and terrorism financing. They assert that the operation now appears aimed more at score-settling between the provincial and federal governments than at genuinely eradicating terrorism from the region.

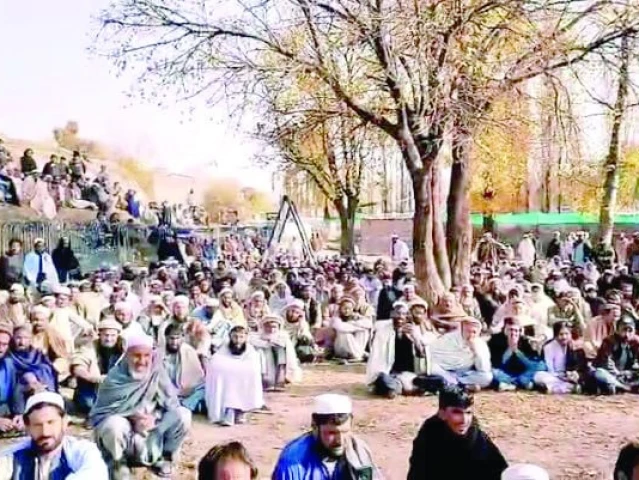

Government officials occasionally address grand tribal jirgas, but only as a formality, and never involve them in crucial policy decisions that affect the tribal region’s future. This systemic exclusion at the national level has further alienated the people of the tribal areas, preventing them from becoming genuine stakeholders in state affairs.

The priorities of both the federal and provincial governments are evident: there is only one Pashtun minister in the federal cabinet, while the current K-P provincial cabinet includes no ministers from the southern districts — the region worst hit by militancy.

On the counter-narrative front, the government has deployed people largely unfamiliar with the complex ideological factors driving violence carried out in the name of jihad. For example, renowned Islamic scholars from the very schools of thought from which most jihadists emerge could challenge extremist narratives on purely ideological grounds — independently and organically, without any state pressure.

However, some media channels quickly seize on these statements, portraying them as part of a state-sponsored effort and using misleading captions that immediately undermine their credibility. Meanwhile, when independent scholars speak out, militants often respond with death threats. Instead of offering protection, authorities abandon them, leaving some dead and others forced into hiding. This, in turn, discourages other scholars from speaking out.

On the kinetic front, a consistent pattern has been observed: when militant groups feel unable to confront the military, they retreat into rugged terrain in other tribal districts or flee across the border into Afghanistan, only to return once military pressure subsides. They simply relocate, wait, and reorganise to strike back. Meanwhile, local civilians emerge as the primary victims of the unintended consequences of operations.

Also, in winter, militants typically enter a hibernation phase, waiting for spring to resume their activities. This had been the consistent pattern during the Afghan Taliban-led insurgency in Afghanistan for two decades. The TTP follows the same cycle. Spring offensives are meant to mark the end of the winter “lull” and the start of the fighting season, as warmer weather makes snow-covered mountain passes more accessible. Launching operations in harsh winter rarely achieves the intended objectives, primarily because militant presence in areas like Tirah is limited during heavy snowfall.

The same dynamic occurred during last year’s short-term “targeted operation” in Bajaur District’s Lowi and War Mamund sub-districts, which left around 55,000 residents displaced, according to local lawmaker Nisar Baz from the area.

According to recent ground reports, militants have staged a comeback in the same areas, albeit in smaller numbers than before the operation. This may be a tactic to test the region before deploying additional reinforcements. The success of a security operation is often measured by body counts and territory reclaimed, rather than by strategic, long-term stability achieved through good governance, institution-building, and the extension of the state’s writ — through service delivery and by making locals active stakeholders in state affairs. In the past, post-operation phases in the tribal areas often involved imposing stricter restrictions on residents to enforce the state’s writ, rather than efforts to ease their lives, resulting in alienation and unrest among local communities.

Kinetic actions are essential, but they must be integrated into a broader long-term vision that includes proper planning and collaboration with local communities and the provincial government.

The biggest question surrounding any operation in Tirah is its legal standing. The decision by a 24-member local jirga to vacate houses by January 10 is highly questionable, as neither the jirga nor its draft carries legal authority. Following the merger of FATA into K-P and the abolition of the Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR), which had previously provided legal cover for jirga decisions, the provincial government now holds the authority to approve such operations.

On the other hand, apart from lacking legal standing, the special assistant to the K-P chief minister on information, Shafi Jan, during a TV talk show, alleged that coercive measures had been used against the 24 jirga elders to sign the agreement — an allegation rebutted by the authorities.

Earlier, federal lawmaker Iqbal Afridi told BBC Urdu that elected representatives from the affected area were neither informed nor consulted about any operation or the displacement of local tribesmen. This reflects an utter disregard for established protocols and procedures, which is likely to further deepen mistrust between the province and the federation.

To effectively address the root causes of militancy, a unified strategy involving both the federal and provincial governments is required, as the provincial government is responsible for implementing post-operation measures to tackle the socio-economic challenges arising from counterterror operations. If the provincial government does not back the federal government’s initiatives, kinetic action risks becoming counterproductive on humanitarian, political, and strategic fronts — ultimately benefiting the militants.

The treatment of erstwhile FATA since its merger with K-P suggests that the historical neglect it faced during its autonomous status persists. On the ground, FATA’s condition has seen little improvement despite official claims. This is evident from the appointment of Mubarak Zeb as special assistant to the prime minister on tribal affairs, who has proven largely ineffective in addressing the region’s plight. His conspicuous absence during key developments, including the ongoing Tirah crisis, exemplifies the state’s continued apathy toward the region.

Successive federal and PTI-led provincial governments have mishandled FATA, treating it worse than even during its semi-autonomous past. Despite committing 3% of the divisible pool under the NFC award to fast-track FATA’s development and integration, the federal government has failed to ensure consistent and equitable distribution.

Moreover, funds allocated to former FATA have lapsed due to successive K-P governments’ gross incompetence and mismanagement. With no visible shift in the attitude of either federal or provincial authorities, prospects for meaningful improvement in the region’s plight remain bleak.

The author is an Islamabad-based journalist and analyst who covers militancy, jihadist movements and related security issues in the region and beyond.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ