Climate change linked to frequent landslides in Pakistan

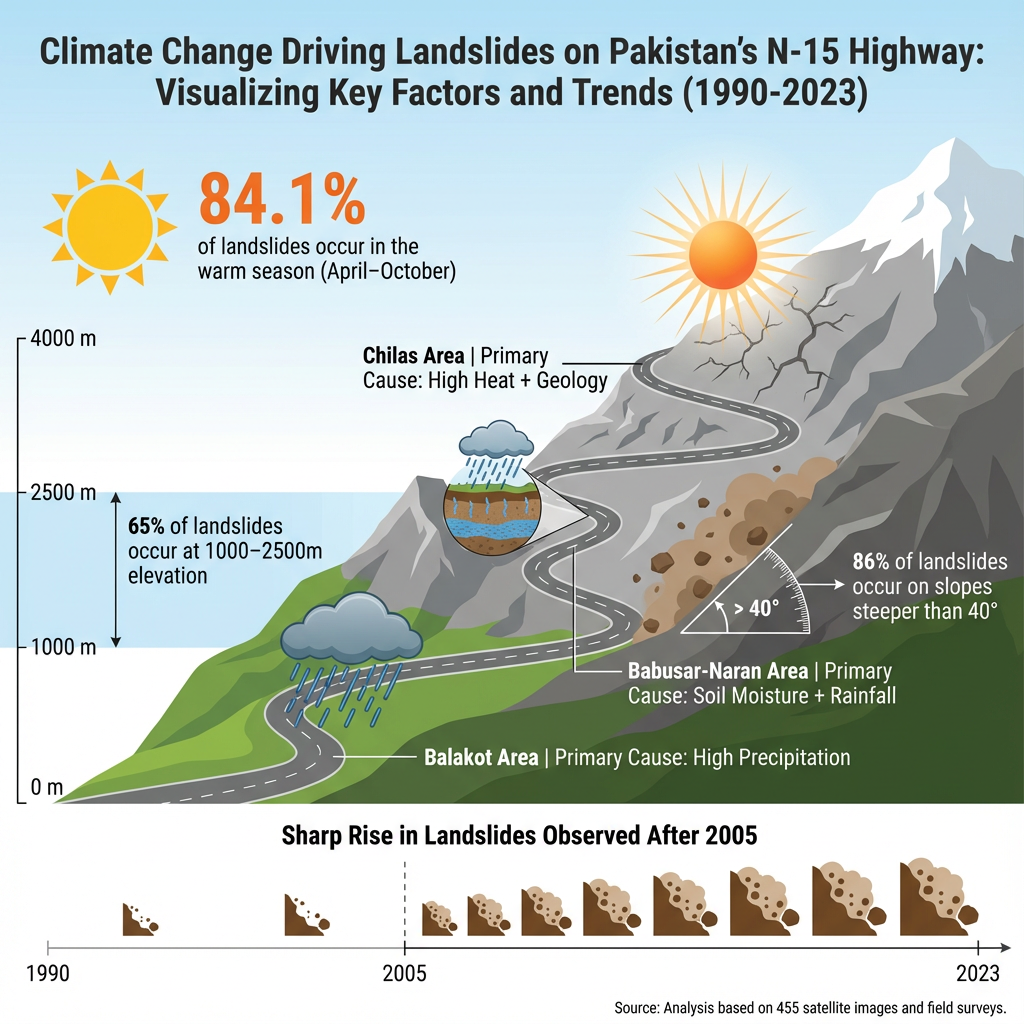

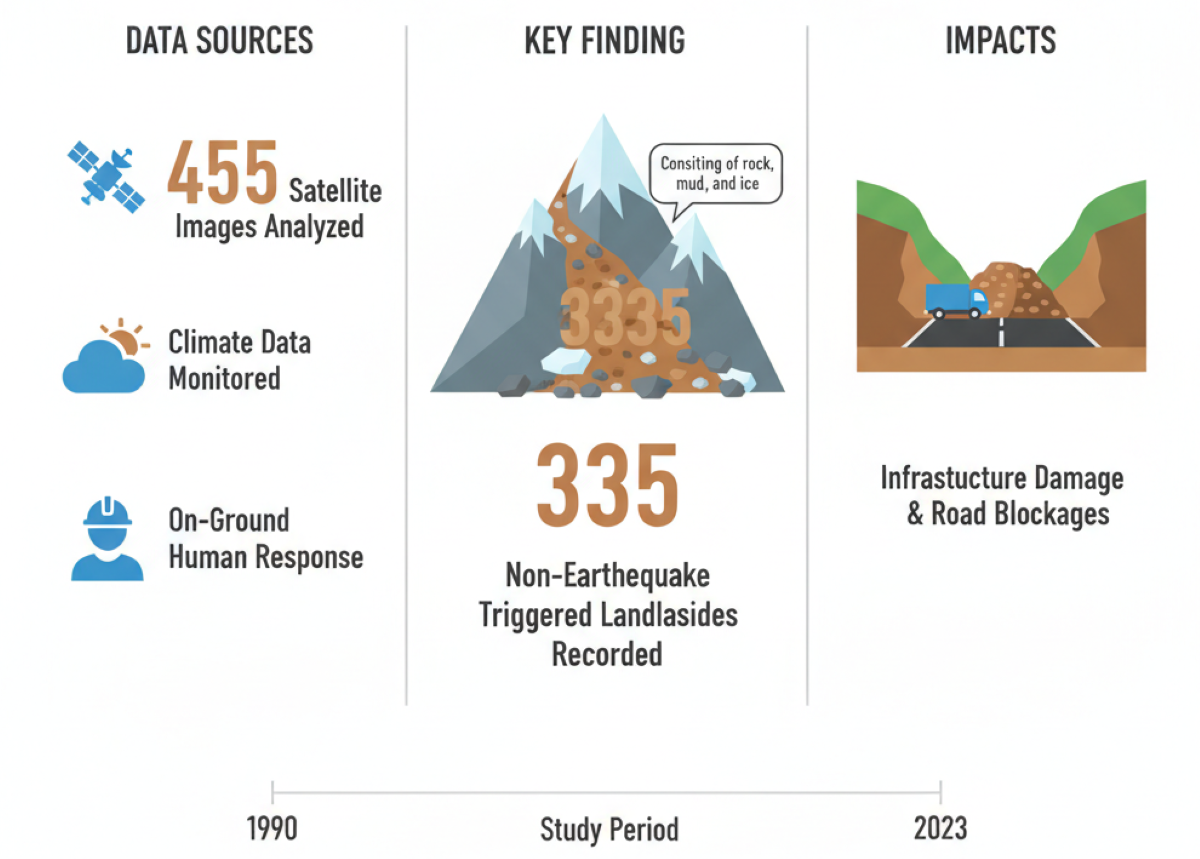

Researchers record 335 non-seismic landslides, damaging roads with rock, mud and ice during a period from 1990 to 2023

The erratic patterns of heat and rain are triggering landslides in Pakistan, even on a very busy and attractive mountainous route dubbed the 'tourism highway'.

Pakistani and Chinese experts studied the N-15 highway, which covers the scenic areas of Balakot, Babusar Top, Naran and Chilas.

The team studied 455 satellite images, climate data and on-ground human responses during a period from 1990 to 2023, and found out at least 335 landslides took place (not triggered by any earthquake), sending rocks, mud and ice crashing onto the infrastructure and blocking the highway.

Scientists used a three-step research framework to reach the conclusion. First, they acquired images from Landsat and Sentinel-2 satellites used for earth observation to observe the area remotely.

Google Earth images were downloaded in the second step to verify the landslides and boundaries of the incidents.

In the third step, the team surveyed the areas where landslides had been indicated by earlier satellite imagery.

Data also confirms warming and rising precipitation in the area from 1990 to 2023, which aligns with the gradual rise of landslide events.

The team also studied daily meteorological data – soil moisture, heat, precipitation, snow cover, vegetation – and concluded that landslides increased during the study period. However, a major increase in landslides was noted after 2005 due to the rise in temperature, snowmelt and precipitation.

Data analysis also shows that more landslide incidents (84.1%) occurred in the warm season from April to October, which needs close monitoring and an early warning system in the area.

Landslide dynamics are different due to the diverse geological makeup of the areas. For instance, Balakot holds sub-tropical conditions where high precipitation (water in the form of ice and rain) is the main cause of landslides.

Area from Babusa Top to Naran is alpine (above the tree-line) where soil moisture and precipitation trigger landslides, while Chilas is a semi-arid region where geological features and heat are the main causes of landslides.

So, the study provides a good understanding of three different climatic-mountain regions for future risk assessment, infrastructure planning, early warning systems and disaster prevention.

Monitoring station was established by Dr Bazai's team from CPJRC and KIU for monitoring the Glacier avalanche and landslide .PHOTO: NAZIR AHMED BAZAI

Climate-related calamities

Rising temperatures speed up snow and ice melt and thaw the frozen ground, increasing underground water and pressure. At the same time, changes in rainfall make surface runoff and soil wetness worsen, both of which raise the risk of landslides. The data also shows these extreme changes especially after 2005.

Slippery slopes

Though geology, soil type, moisture and vegetation at any mountain play an important role in landslides, mountains with steep slopes are more vulnerable to mudslides.

Researchers used 12.5m ALOS PALSAR elevation data to calculate slope and height of mountains. They also used Google Earth images (3.4m resolution) and field visits to confirm satellite-based findings.

Researchers found that over 86% of incidents happened on slopes steeper than 40°, and 65% occurred at heights between 1000–2500 meters. These facts are helpful in early warning and planning to avoid disasters.

On-ground analysis

Two field visits were made along the N-15 Highway in August 2022 and April 2023 to improve data accuracy. Local residents with geohazard knowledge were surveyed to gather details on nearby landslides posing risks to communities.

Satellite imagery and data are good tools in warning of potential collapse of mountainous mass.

“In 2022, satellite imagery highlighted instability in regions like Balakot, which was later confirmed during our field surveys. In these field investigations, we directly observed landslide activity, such as displaced debris and damaged infrastructure, further validating the satellite data,” said Nazir Ahmed Bazai from the China Pakistan Joint Research Center on Earth Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).

“Through interviews with locals, we learned how they’ve adapted to these risks, avoiding high-risk areas during the monsoon and even temporarily relocating in extreme cases. However, limited infrastructure and resources mean that these responses are often reactive, not proactive, making the community vulnerable. Integrating local knowledge with scientific data is crucial to improving early warning systems and building long-term resilience,” he added.

Long-term resilience

Nazir Ahmed Bazai urges both - natural and non-natural ways - to tackle the problem. He proposes adopting low-cost bioengineering methods by planting deep-rooted vegetation to stabilise high-risk areas like Balakot and Naran.

“Additionally, building protective barriers and improving drainage systems along the highway would help reduce the frequency and severity of landslides. Real-time monitoring with low-cost sensors tracking rainfall, soil moisture and snowmelt, especially near Babusar Pass, can provide timely warnings for both locals and tourists.

Furthermore, community education programmes focused on landslide evacuation procedures and monitoring tools would enhance local preparedness,” said Bazai.

Counting fatalities

In 2019, Dr. Melanie Froude, from the geography department of the University of Sheffield, and Dave Petley, currently the Vice Chancellor of the University of Hull, compiled a Global Fatal Landslide Database. It shows 1,583 deaths from 215 non-seismic (not earthquake-triggered) landslides in Pakistan from 2004–2016.

She urges on 'research, regulate and educate' to avoid such disasters.

Speaking to The Express Tribune, she said landslides are considered a local problem, and management of these hazards requires an understanding of the local geo-environmental context.

“Research to understand how hillslope materials (rock and soil) respond to changes in the local environment (e.g., rainfall, addition of weight by a building, change in slope angle) helps identify when slopes may become unstable,” she added.

The second point is regulate, which means inspection and enforcement of rules. She urges following national guidelines on construction methods, building size and foundations for homes in a mountain environment.

Education is much needed, as by understanding of what causes a slope to collapse (research), we can provide appropriate information to different groups of people.

“At a very technical level, engineers use sophisticated models to design a stable hillslope: its shape, where barriers or reinforcements should be placed, and where drainage pipes should be installed. Their judgements are informed by the results of rigorous research. For many, paying for technical expertise is not an option. Providing straightforward guidance on low-cost, safe slope engineering that is locally relevant for the geology and climate is important,” she added.

Froude said the community and NGOs are important in warning local people about landslide risk.

“One important low-cost solution is to maintain vegetation on slopes and install proper drainage for rainfall,” she said.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ