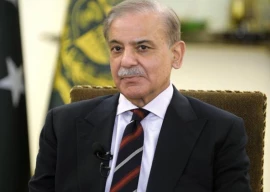

Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif recently praised the remarkable success story of Shenzhen, heralding its evolution into the city of the future. Once a modest fishing village, Shenzhen has emerged as a dynamic hub of modern technology, development, and innovation. With its GDP growing steadily, Shenzhen’s journey of transformation commenced in 1978 with a modest GDP of $40 million, soaring to an impressive $500 billion with a population of 13 million.

Impressed by Shenzhen’s achievements, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif announced Pakistan’s intention to adopt the Shenzhen model of development. While this declaration demonstrates a positive step towards learning from Shenzhen’s experience, it raises the question: Can Pakistan truly replicate Shenzhen’s success?

Before answering this question, it is essential to examine the factors driving Shenzhen’s transformation. What reforms did China implement? What institutional mechanisms and infrastructure facilitated Shenzhen’s growth?

China initiated its reform process by implementing political and economic changes. Shenzhen was granted greater political and economic autonomy, starting with Guangdong Province declaring Shenzhen equivalent to a provincial capital in 1981 and initiating infrastructure upgrades. By 1988, the central government elevated Shenzhen to provincial status, significantly boosting its decision-making and implementation powers. In 1992, the government further empowered the town by granting it legislative authority, enhancing its capabilities for decision-making and implementation. Moreover, the central government provided increased autonomy in financing, investment, and trade decision-making. Shenzhen also spearheaded contractual job experiments, signifying a notable departure from China’s socialist principles, which typically prioritize job security. These reforms aimed to enhance Shenzhen’s attractiveness to foreign investors.

Experts widely agree that legislative power and decision-making autonomy were pivotal in revolutionising Shenzhen’s development. Leveraging the trust and authority granted by the Central government and the Communist Party of China, Shenzhen implemented numerous innovative practices. One notable example is the introduction of the “government approval within 24 hours” concept and model, which was further expedited by adopting and strengthening the one-roof model, consolidating all services under one administrative umbrella.

On the economic and infrastructural fronts, Shenzhen granted the zone authority to expedite company registration processes. Additionally, zone authorities provided investors with essential services such as electricity, water, and facilitated tax matters. State-of-the-art trade facilitation mechanisms and infrastructure were also established, ensuring efficient import and export operations, alongside robust security measures.

Furthermore, the local government played a pivotal role in Shenzhen’s transformation. Alongside other Special Economic Zones (SEZs), local governments ensured high-quality infrastructure including roads, utilities, and telecommunications. Basic services were conveniently provided at investors’ doorsteps, with urgent services guaranteed within 24 hours. Local governments expanded their scope to support SEZs by offering accounting, legal, business planning, marketing, and import-export assistance, as well as skills training and management consulting. This comprehensive support empowered investors to navigate local regulations effectively and refine their strategies, fostering confidence and comfort among investors and attracting further investments to the region.

In essence, Shenzhen’s success can be attributed to its autonomous decision-making, freedom to innovate, and clear chain of command. With minimal interference from other ministries and departments, Shenzhen had the authority to address issues efficiently and collaborate closely with the CPC, central, and provincial governments. These factors enabled Shenzhen to fulfil its promises, meet targets, and propel China towards modernisation and development.

Crucially, overseeing these reforms was the influential, dedicated, and forward-thinking leader, Xi Zhongxun, who previously served as deputy prime minister under Prime Minister Zhou Enlai.

Now, the question arises: Can Pakistan adopt and derive lessons from the Shenzhen model? In the current context, learning from it appears to be exceedingly challenging for various reasons. Let’s consider the example of the CPEC Authority. Established to streamline and expedite work on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the Authority lacked decision-making and implementation powers. Despite these limitations, it endeavoured to facilitate investors. Regrettably, opposition parties opposed these efforts, utilising parliamentary means to weaken the Authority. Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), in particular, vehemently criticised the concept and almost disbanded the CPEC Authority during its tenure.

Secondly, there is a tug of war among political parties to claim credit for CPEC. Each party tends to credit themselves for CPEC’s successes while blaming others for its shortcomings. PML-N, PPPP, PTI, and JUI-F are prominent players in this credit-seeking game, making it challenging to build consensus for innovative programs like the CPEC Authority. Furthermore, they are hesitant to support initiatives that don’t enhance their own prominence.

Thirdly, government ministries and departments vie for prominence in CPEC projects, leading to unnecessary competition that complicates project implementation and deters investors. This mentality has significantly impacted the effectiveness of the CPEC Authority, rendering it non-functional.

Fourthly, Pakistan faces a weak chain of command, with provinces and the federal government often at odds due to conflicting preferences. Provinces tend to shift blame onto the federal government, exacerbating tensions. The complexities introduced by the 18th Amendment have further strained relations, turning CPEC into a new battleground for competition between federal and provincial governments. This has hindered progress, particularly in completing SEZs.

Fifthly, local governments in Pakistan are either non-functional or non-existent, as all political parties are complicit in weakening them and delaying local government elections. Despite advocating for the 18th Amendment, they are unwilling to grant power to local governments, leaving them without financial resources to provide essential services like roads, water, electricity, and sewage. Given these challenges, learning from the Shenzhen model appears extremely difficult, if not impossible. However, if the government is genuinely committed, the SIFC offers a promising opportunity to implement elements of the Shenzhen model.

THE WRITER IS A POLITICAL ECONOMIST AND A VISITING RESEARCH FELLOW AT HEBEI UNIVERSITY, CHINA

1729080111-0/BeFunky-collage-(63)1729080111-0-405x300.webp)

1730838202-0/Trump-(1)1730838202-0-165x106.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ