Monsters and mourning: Bearing witness to patriarchal violence through art

On artistic displays of grief following social tragedy and remembrance devoid of empathy

We are living through times of incapacitating grief. With the uptick in patriarchal violence, it comes as no surprise that the burden of this grief is carried disproportionately by cis and trans women. The past two weeks have seen the internet inundated by a constant stream of traumatic news of femicide and gender-based violence. From the high-profile murder of Noor Mukadam by Zahid Jaffer to the facial mutilation of a woman by her ex-husband in Rawalpindi, the recent days have been punctuated by moments of profound sorrow over the loss of lives, futures and freedoms.

If there is one thing that can be said about these tragic losses, it is that they demand to be grieved, or at the very least, mourned. While grief is an emotion, inherently personal, it can be shared through the social act of mourning. However, not all mourners are made equal, an observation that becomes all too jarring in the age of public displays of emotion and opinion on social media.

Art and public mourning

To mourn is to bear witness to grief and to insist on remembrance of all the women whose lives have been lost to or fundamentally fractured by patriarchal violence. However, remembrance devoid of empathy and an understanding of the hierarchy of grief may quickly devolve into a disservice to the memory of the victims. It is here that a conversation on the ethics of mourning social tragedy and community/gender-based violence becomes imperative.

The murder of Noor was followed by a wide range of public displays of grief on social media. To many women, the loss felt all too personal. In mourning Noor, women mourned their compounding loss of security and freedom in a state that actively denies their grief. Protest art poured in, with women arranging flowers in Noor’s hair in brightly coloured life-affirming portraits, tinged with inevitable sorrow and anger.

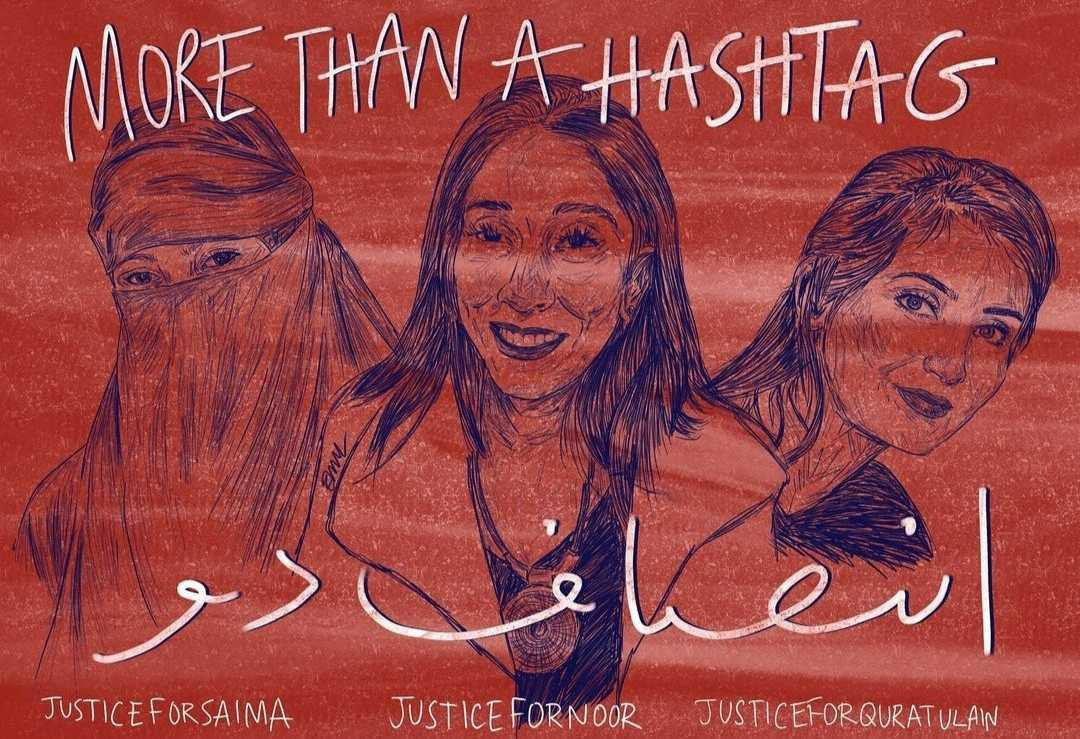

Illustration credit: Emil (Instagram: @padpixie)

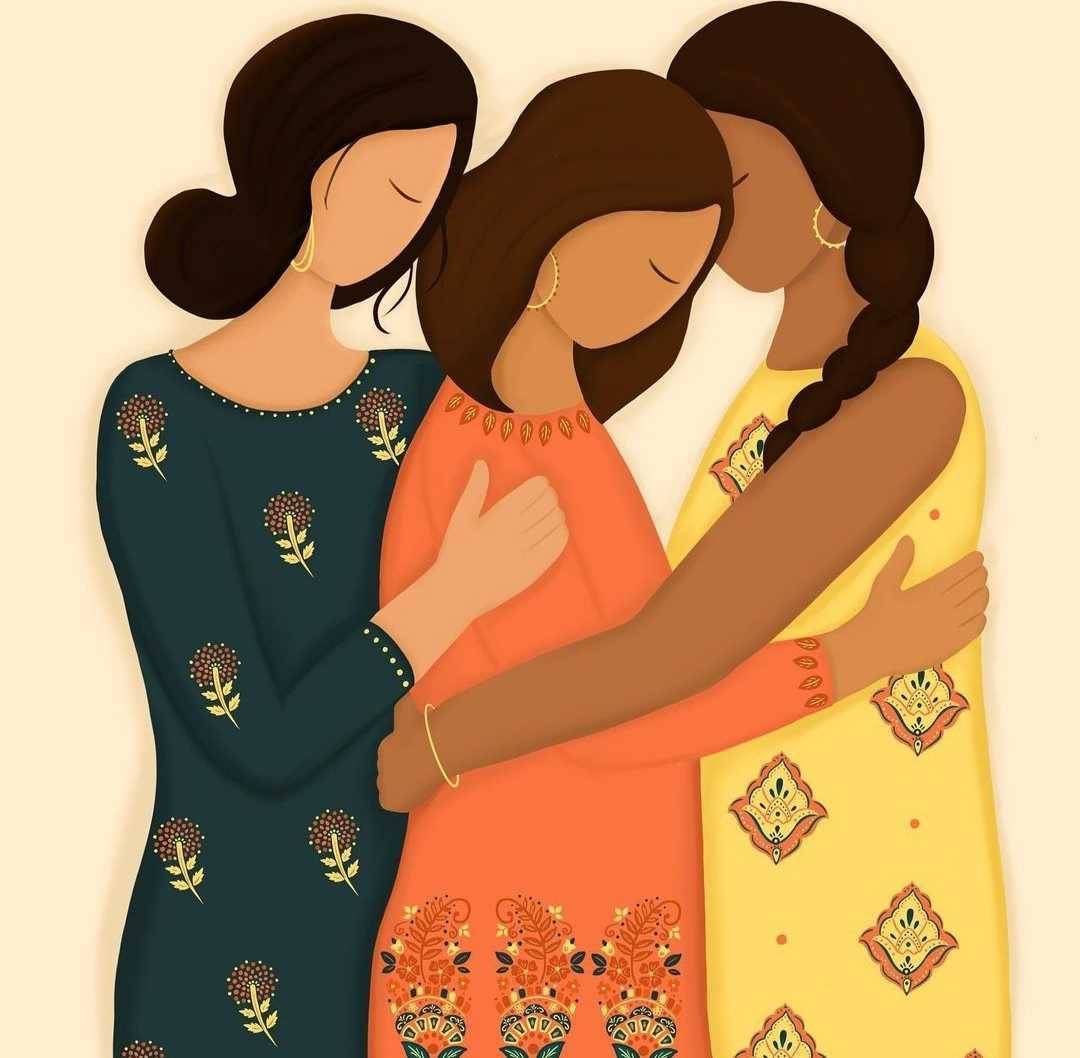

One illustration by digital artist Sarah Imran depicts three women in an embrace, leaning on each other in a message of togetherness in times of unbearable tragedy. Another, by artist Emil, includes portraits of women recently lost to the ongoing femicide in the country. With a hazy red background, in many ways indicative of the tired rage of women living in constant fear, the illustration showcases a demand for immediate justice. In a similar vein, artist Amara Sikander dresses Noor in bold colours in a loud and proud tribute; an active refusal to forget or be silent.

Illustration credit: Sarah Imran (Instagram: @sarahzimran)

Illustration credit: Amara Sikander (Instagram: @amarasikander)

Artistic expressions of solidarity and anger have emerged from a wide array of social movements. One of the most recent examples can be found in the protest art following the murder of George Floyd by white police officers, which triggered the Black Lives Matter movement. However, when it comes to matters of violent oppression, a thin line exists between art meant to serve as a tribute to the victims, and that which offers traumatic depictions of the violence enacted upon them.

The limits of representation

Following the outrage over the murder of Noor, Instagram-famous illustrator Abdal Mufti posted an illustration of a grinning Zahid Jaffer, covered in blood, at the supposed scene of the crime. Clad in a suit and tie in his widely-circulated photograph, the artist made the key change of dressing the murderer in an unkempt banyan and black trousers in an effort to “paint him as a symbol of the monsters that we hide among us” seemingly fueling the inaccurate assumption that all ‘monsters’ must be working-class.

The reaction to the illustration was knee-jerk and overwhelmingly negative. The artist’s comment section was flooded with demands for the distressing illustration to be taken down. Abdal Mufti refused. He went on to post another illustration, this time of himself inside a box, surrounded by a crowd of mostly females as a depiction of his victimhood. The murdered women can wait.

Grief denied

Abdal Mufti’s art is devoid of any form of intersectionality, an empty act of mourning that offers nothing to the victims or the cause. The illustration forces the family of the deceased to relive the inhumane conditions of their loved one’s death, it forces victims of patriarchal violence to relive their trauma, and it serves as an intimidating reminder to women everywhere of the extent of their vulnerability in a violently patriarchal state. This is not to question the artist’s original intentions, however morphed they may have become over the course of the controversy, but to ask him to put his emotions in conversation with the grief of those on whom the tragedy has had a much greater impact.

The insistence of the artist to label Zahid as a monster serves to do nothing more than otherise the murderer. Zahid becomes a scapegoat, a one-off, and all men are subsequently absolved of the responsibility of taking action towards ending the violence that is systemically entrenched within their masculinity. The depiction is a caricature of the man at the centre of the violence, dehumanising him. The effort to depict Zahid as belonging to the tail end of the class spectrum serves to separate him from the ‘educated’ middle and upper class. However, the cult of violent hypermasculinity is a highly inclusive one, filled to the brim with leering men from all socio-economic backgrounds.

The art of empathy

Perhaps more outrageous than the grotesque illustration was the artist’s outright refusal to listen. Pakistani women live with the burden of grief repeatedly invalidated. To take away their right to demand how one of their own be mourned is nothing more than another act of violence. Where are the mourners to bear witness to this undeniable grief? With distressing and self-serving depictions of violence by male artists, the act of witnessing takes a backseat, morbid voyeurism quick to take its place. Women do not wish to see the same blood that runs through their veins splattered across the walls in some misplaced attempt at ‘remembrance’. There is no cathartic value to this art, there is only chaos.

All this is not to say that trauma and violence cannot be depicted through art, but that they cannot be depicted without empathy. Art can be triggering, but not without complexity. Understanding the circumstances of those against whom the violence is done is imperative in creating any art that strives to put an end to that violence. Art is inherently about power, and it needs to remain sensitive to the dynamics of it. It is here that mourning becomes a political tool. Who gets to detach themselves from tragedy enough to depict it through art? Which voices need to be at the forefront of the fight for any form of justice?

Tragedy will strike again. When it does, stop and look around. Listen. The heavy grief of the bereaved will be loud even in the cacophony of voices and clashing opinions. Mourn with them. Bear witness to their pain and anger. There will be other opportunities for you to speak. For now, let them grieve.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ