Speak your mind: brain implant translates thought to speech

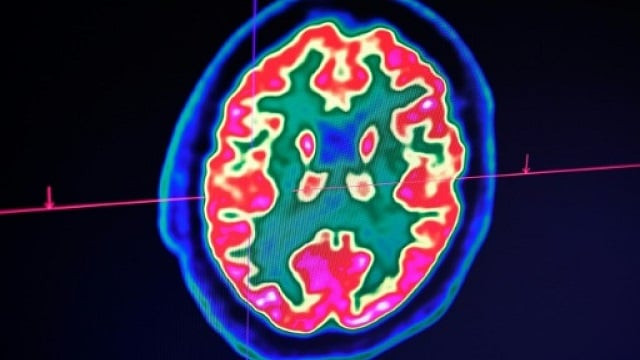

Researchers said they had successfully reconstructed 'synthetic' speech using an implant to scan brain signals

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, said they had successfully reconstructed "synthetic" speech using an implant to scan the brain signals of volunteers as they read several hundred sentences aloud. PHOTO AFP

Several neurological conditions can ruin a patient's ability to articulate, and many currently rely on communication devices that use head or eye movements to spell out words one painstaking letter at a time.

Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, said they had successfully reconstructed "synthetic" speech using an implant to scan the brain signals of volunteers as they read several hundred sentences aloud.

Scientists revive brain function in dead pigs

While they stress the technology is in its early stages, it nonetheless has the potential to transpose thoughts of mute patients in real time.

Instead of trying to directly translate the electrical activity to speech, the team behind the study, published in the journal Nature, adopted a three-stage approach.

First, they asked participants to read out sentences as an implant on the brain surface monitored neural activity while the acoustic sound of the words was recorded.

They then transformed those signals to represent the physical movement required for speech -- specific articulations of the jaw, mouth and tongue -- before converting these into synthetic sentences.

Finally, they crowd-sourced volunteers to identify words and sentences from the computerised speech.

The recordings are uncanny: a little fuzzy, yes, but the simulated sentences mimic those spoken by the volunteers so closely that most words can be clearly understood.

While the experiment was conducted only with people who could speak, the team found that speech could be synthesised from participants even when they only mimed the sentences.

"Very few of us have any idea of what's going in our mouths when we speak," said Edward Chang, lead study author.

"The brain translates those thoughts into movements of the vocal tract and that's what we're trying to decode."

This could potential open the way for an implant that can translate into words the brain activity of patients who know how to speak but have lost the ability to do so.

'Those thieves stole jewels'

The sentences used in the study were simple, declarative statements, including: "Ship building is a most fascinating process", and "Those thieves stole thirty jewels."

Gopala Anumanchipalli, co-author of the study, told AFP that the words used would add to a database that could eventually allow users to discern more complicated statements.

"We used sentences that are particularly geared towards covering all of the phonetic contexts of the English language," he said. "But they are only learned so they can be generalised from."

The researchers identified a type of 'shared' neural code among participants, suggesting that the parts of the brain triggered by trying to articulate a word or phrase are the same in everyone.

Chinese scientists create monkeys with human brain genes

Chang said this had potential to act as a starting point for patients re-learning to talk after injury, who could train to control their own simulated voice from the patterns learned from able speakers.

Writing in a linked comment piece, Chethan Pandarinath and Yahia Ali, from the Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, called the study "compelling".

"With continued progress, we can hope that individuals with speech impairments will regain the ability to freely speak their mings and reconnect with the world around them," they wrote.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ