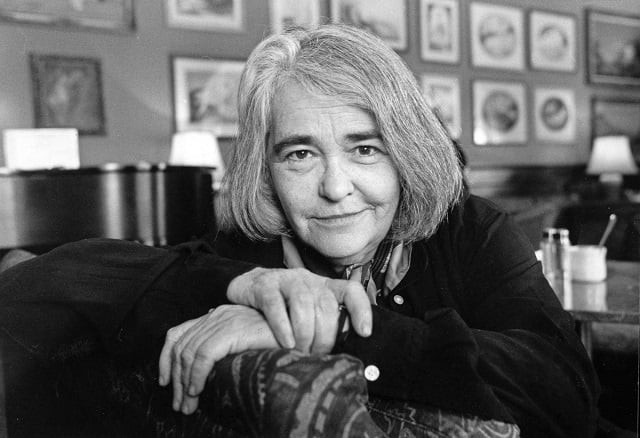

Kate Millet, author of Sexual Politics, dies at 82

She developed unforgettable theory that for women, the personal is political

Kate Millet, author of the groundbreaking 'Sexual Politics'

PHOTO: THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The basis of Sexual Politics (1970) was an analysis of patriarchal power. Millett developed the notion that men have institutionalised power over women, and that this power is socially constructed as opposed to biological or innate. This theory was the foundation for a new approach to feminist thinking that became known as radical feminism.

Sexual Politics was published at the time of an emerging women’s liberation movement, and an emerging politics that began to define male dominance as a political and institutional form of oppression. Millett’s work articulated this theory to the wider world, and in particular to the intellectual liberal establishment, thereby launching radical feminism as a significant new political theory and movement.

If wanting equal rights makes me a feminist, then I’m a proud one!: Sohai Ali Abro

In the book, Millett explains women’s complicity into male domination by analysing the ways in which women are socialised into accepting patriarchal values and norms which challenged the notion that female subservience is somehow ‘natural’.

“Sex is deep at the heart of our troubles…” wrote Millett, “and unless we eliminate the most pernicious of our systems of oppression, unless we go to the very centre of the sexual politic and its sick delirium of power and violence, all our efforts at liberation will only land us again in the same primordial stews.”

Sexual Politics includes sex scenes by three leading male writers: Henry Miller, Norman Mailer and DH Lawrence. Millett analysed the subjugation of women in each. These writers were key figures in the progressive literary scene. Each had a huge influence on the counterculture politics of the time, and embedded the notion that female sexual subordination and male dominance was somehow ‘sexy’.

It was never the intention of Millett to become a career feminist, being much more interested in her art, as a sculptor. But after being featured on the cover of Time magazine, in August 1970, she was catapulted into fame, which led to a backlash from some feminists who accused Millett of styling herself as a movement ‘leader’ – an accusation she rejected.

That December, Time outed Millett as bisexual, and claimed that “[the] disclosure is bound to discredit her as a spokesperson for her cause, cast further doubt on her theories, and reinforce the views of those sceptics who routinely dismiss all liberationists as lesbians”.

At the time the women’s movement was divided over the issue of lesbianism – Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique (1963), had labelled lesbians the “lavender menace” – and many liberal feminists turned against Millett. Yet more than three decades later, the feminist writer Andrea Dworkin wrote of Millett: “Betty Friedan had written about the problem that had no name. Kate Millett named it, illustrated it, exposed it, analysed it.”

Born in St Paul, Minnesota, Kate was raised by strict Catholic parents. Her mother, Helen (nee Feely), worked as a teacher and an insurance saleswoman to support her three daughters after her alcoholic husband, James, an engineer, abandoned the family when Kate was 14. Millett went to the University of Minnesota, graduating in English literature in 1956, and then to St Hilda’s College, Oxford. She taught briefly at the University of North Carolina before focusing on sculpture in Japan and then New York. In 1965, she married the Japanese sculptor Fumio Yoshimura. During their open relationship, Millett had sexual relationships with a number of women.

She went to Columbia University in 1968, and Sexual Politics, based on her doctorate, was published in 1970. She wrote about the impact of her newfound fame in Flying (1974) and followed this up with Sita (1976), about her relationship with an older woman. In 1979, she travelled to Iran’s first International Women’s Day with her then partner, Sophie Keir, a photojournalist. They were arrested and expelled, an experience they documented in their book Going to Iran (1981).

Gender equality: Resistance against feminism about power and privileges, say experts

Millett had been committed to mental health institutions by her family on various occasions and she became an activist in the anti-psychiatry movement. She wrote about her experiences in The Loony-Bin Trip (1990). She also wrote The Politics of Cruelty (1994), in which she railed against the use of torture, and Mother Millett (2001), about her relationship with her mother.

In 1998 Millett wrote a piece for the Guardian, The Feminist Time Forgot, in which she said: “I have no saleable skill, for all my supposed accomplishments. I am unemployable. Frightening, this future. What poverty ahead, what mortification, what distant bag-lady horrors, when my savings are gone?”

In her later years, Millett and Keir lived on a farm in Poughkeepsie, New York state, where at first they sold Christmas trees, and later established a women’s art colony. In 2012 she received the Yoko Ono Lennon Courage award for the arts, and in 2013 she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in New York.

Millett’s marriage to Yoshimura ended in 1985. She is survived by Keir, whom she married in later life.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ