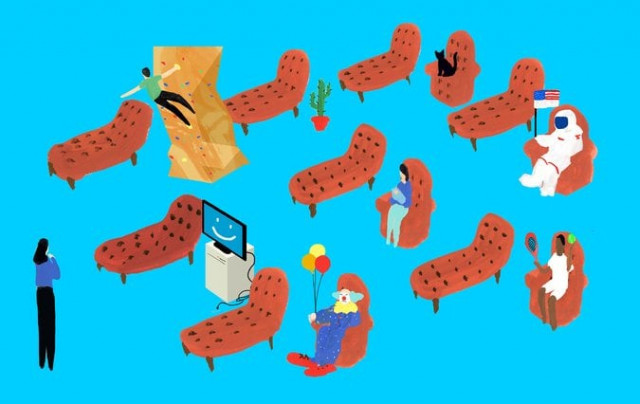

Dear Google, is there a shrink for that?

The Internet has shifted therapeutic landscape

PHOTO: JON HAN

This is arguably the single question helping to reshape the modern psychotherapeutic landscape.

Call it boutique therapy; a swirl of contemporary tastes and consumer expectations that has yielded a collection of psychotherapeutic options specially designed for almost any circumstance in which humans could find themselves.

The search for self

Forget the old distinctions between therapists who specialise in mood disorders versus those who do marriage counseling. The new niche market is exponentially more refined.

In need of a therapist to help get your start-up going? Check. To help you tackle the particularities of life as a Hasidic Jew? As a Muslim? Check, check. To help you end a relationship? To grieve the loss of a pet? To better understand the tapestry of female sexuality? To struggle through the issues of young adulthood? Check.

Perhaps nowhere is this phenomenon more evident than in the realm of psychotherapies designed for people who identify as L.G.B.T. Therapists, both gay and straight, have increasingly started practices geared specifically toward lesbian, gay, bisexual and, most recently, transgendered patients. (Not to mention those patients who prefer not to identify with any one category.)

Get lifestyle news from the Style, Travel and Food sections, from the latest trends to news you can use.

For Matthew Silverstein, a psychologist in West Hollywood, Calif., this development springs from dire necessity. “There’s a tortured history of practices that have been called psychotherapy,” Dr. Silverstein said, referring to notorious techniques like “conversion therapy” that purport to change patients from gay to straight and that continue to be practiced to this day. “There’s still a vulnerability that many L.G.B.T. patients feel when coming into a psychological treatment,” he said.

For Dr. Silverstein and others, the advent of specialisation has created “safe refuges” for patients who for so long were without recourse to anything of the kind. “Until the 1970s, we simply didn’t have the tools,” he said. “There wasn’t an understanding of gay identity, or of gayness as a cultural or developmental process.”

The toll of childhood trauma

For the psychologist Douglas Sadownick, a colleague at Antioch University in Culver City, Calif., there is an added layer of emphasis. “We work on the assumption that gay people have their own psychology, they have their own blueprints,” he said.

It is with this conviction that Dr. Sadownick runs one of the country’s first and only clinical psychology master’s programs dedicated to L.G.B.T. studies, which he helped found at Antioch in 2006. Here, the training to become an “L.G.B.T. affirming” therapist includes a distinctive curriculum: Plato’s Symposium and the poems of Sappho and Walt Whitman are all assigned reading.

For Dr. Sadownick, the essential qualities of an L.G.B.T. affirming therapist come down to two fundamental capabilities: to be able to identify one’s own “internalised homophobia,” often operating outside of conscious awareness, and “to treasure being gay, as good for society, good for evolution,” he said. “To be aware that this idea of being L.G.B.T. may have a lot more potential than we’ve given it.”

Undoubtedly, the Internet has contributed to the shifting therapeutic landscape. Where before, word of mouth was crucial to the search for a therapist, prospective patients are now likely to take to the web, and faced with thousands of anonymous possibilities, look for some way in which to determine who may be the best fit, whose boxes check their own boxes.

It’s not unlike how one may proceed through OkCupid, seeking potential mates who share a taste for George Orwell, Judaism and taco trucks, in the hope that these commonalities actually mean something.

And many therapists, in turn, feel the pressure to fold themselves into recognisable categories. For Rachel Sussman, a psychologist in New York who self-describes as a “relationship specialist” (from first date to breakup), it seemed necessary to carefully brand herself to build a practice.

“I have a marketing background,” she said. “I became a therapist as a second career. And I knew I had to hit the ground running. Once upon a time, you would just hang a shingle and wait for people to come to you. I don’t think that happens anymore.”

And then there are those therapists who become accidental specialists, stumbling into a niche, as Lawrence Josephs did, after appearing in a documentary that made its way to YouTube. “Thanks to Google I am getting more patients looking for someone they think of as an infidelity expert,” he wrote last year in The New York Times.

Like so much to do with psychotherapy itself, the new specialization is largely an urban phenomenon. Take Jocelyn Charnas, known as “the wedding doctor” in certain New York circles, who came to her specialty through personal experience.

A practicing psychologist, she had recently gotten married and was aware that there was all too little conversation revolving around the psychological challenges of the experience. “When you get engaged, it’s the ring, the venue, the flowers, which is all wonderful and interesting, but nobody seemed to be talking about the universal experience that this is also difficult,” she said.

For Dr. Charnas, weddings are not just weddings, but rather pressure-cooker moments that contain layer upon layer of psychologically fraught material. “Typically, it’s really not whether you’re having roses or lilies that is keeping you up at night,” she said. “While that may be the manifest content of it, the underlying content could be a number of things, like fears of disappointing your mother, or disappointing yourself. There are so many latent emotions.”

Dissociative identity disorder

Thus, for Dr. Charnas, within weddings lies the very fullness of human experience. This is what makes every case different, every stressed-out bride-to-be distinct from the last.

In Los Altos, Calif., the psychologist Howard Scott Warshaw has developed his own brand as “The Silicon Valley Therapist,” specializing in everything that he says makes Silicon Valley unique: the particular personality type that is suited for computer programming but less adept at parsing human ambiguity, the environment that seems to expect nothing less than extraordinary achievement.

“Some of these engineers, they love the software world, because it provides a metaphor of looking at life that really makes sense and facilitates their entire worldview,” Mr. Warshaw said. “So if you’re going to deal with someone like that and you can’t speak that language, there’s going to be a real communication problem.”

And because Mr. Warshaw was a computer engineer before he became a therapist, he believes he has the necessary knowledge to communicate with his clientele. “I’ve done the job they’ve done,” he said. “I’ve been in the pressures they’ve been in. I really understand what it is to go through a software development cycle. So I can hear them in a way that some therapists without this background simply can’t.”

But many clinicians would contend that shared experience is irrelevant to the treatment of their patients. “This whole idea that when you walk in the door, there’s a template for: ‘We are the same, and out of that sameness we can build an immediate rapport,’ to me that seems like a very problematic notion,” said Michael Garfinkle, a psychoanalyst in New York. “My basic orientation, especially at the beginning, is a great curiosity and openness to what I’m hearing. There’s a recognition that it takes a long time to learn the way that someone speaks.”

Dr. Garfinkle is often asked by prospective patients, “Do you have a specialty?”

This is how he likes to respond: “My youngest patient is 9, my oldest patient is 82. My patient who’s most well is mildly anxious, my most severely ill patient, so to speak, is someone who has been in and out of hospitals with schizophrenia for most of his life.”

Similarly, Justin Shubert, a psychologist in Los Angeles and the director of Silver Lake Psychotherapy, is quick to note that seeing a therapist whose label matches your label is not without its hazards.

“It can be limiting because you may end up with someone with a narrower perspective,” Dr. Shubert said. “Just because someone understands what it’s like to work with a Hasidic Jew, doesn’t mean that they understand what it’s like to have two sisters, or to be depressed.”

One may also wonder: Where is the line between Mr. Warshaw’s kind of highly targeted Silicon Valley therapy and the less explicitly psychological work of a life coach? For Mr. Warshaw, the distinction is clear. “In coaching I’m working to maximize your performance in a specific activity right now,” he wrote in an email. “In therapy I’m working to maximize your potential and who you are, then you can take that to any endeavor you care to.”

But in all this talk of software development cycles and maximised potential, it’s easy to lose sight of something much more fundamental, a persistent truth that surfaces again and again when therapists talk about what actually helps their patients. As Dr. Shubert observed, “Regardless of the technique that the therapist uses, it’s the relationship itself that heals.”

His perception is hardly newfangled. Freud himself had something to say on this subject. In a letter to Carl Jung, written in 1906, he put it thus: “Psychoanalysis is, in essence, a cure through love.”

This article originally appeared on The International New York Times, a global partner of The Express Tribune.

1726734110-0/BeFunky-collage-(10)1726734110-0-208x130.webp)

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ