China cuts mobile service of Xinjiang residents evading internet filters

Chinese officials say reason behind electronic surveillance is to stop spread of religious extremism via internet

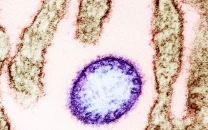

Urumqi , in China's Xinjiang region. The area has long been home to experiments in Internet surveillance and censorship. PHOTO: AFP

Starting last week, shortly after terrorist attacks in Paris, the local police began cutting the service of people who had downloaded foreign messaging services and other software, according to five people affected.

Illegal Money Transfer: China busts biggest ‘underground bank’

The people, who spoke on the condition of anonymity over concerns about retaliation from local security forces for speaking to foreign news media, all said their telecommunications provider had told them to go to a local police station to have service restored.

“Due to police notice, we will shut down your cellphone number within the next two hours in accordance with the law,” read a text message received by one of the people, who lives in the regional capital of Urumqi. “If you have any questions, please consult the cyber police affiliated with the police station in your vicinity as soon as possible.”

The person said that when she called the police, she was told that the service suspensions were aimed at people who had not linked their identification to their account; used virtual private networks, or V.P.N.s, to evade China’s system of Internet filters, known as the Great Firewall; or downloaded foreign messaging software, like WhatsApp or Telegram.

With debates continuing in Europe and the United States about how heavily to encrypt communications sent through smartphone messaging applications that could mask terrorist plots from law enforcement, the move in China underlines Beijing’s determination to control and monitor information online. The debate in the West also has influence in China, said Nicholas Bequelin, the East Asia director for Amnesty International in Hong Kong.

“With the West generally going backward in terms of protecting privacy and freedom of expression, China is comforted in its longstanding position that it is the arbiter of what can be said or not,” he said.

The action also shows that despite spending billions of dollars to create one of the world’s most sophisticated Internet censorship and surveillance systems, blind spots abound. The Chinese government has long focused on software that circumvents the Great Firewall, like virtual private networks. But the move to suspend mobile phone accounts linked to the software demonstrates a new level of urgency.

Beijing has at times bolstered its filters against virtual private networks, and has been taking increasingly aggressive steps over the last year to censor Internet content. In March, China turned the Great Firewall into a powerful weapon that redirected incoming traffic to sites abroad that it deemed hostile. The campaign for tighter Internet control is led by Lu Wei, China’s Internet czar since 2013, who has been reining in social media and has implored foreign tech leaders and policy makers to show “respect of national sovereignty” on the Internet.

Pakistani develops software that can erase unwanted information from internet faster than Google

Any move to constrain users of virtual private networks across the country would most likely hamper foreign and local businesses alike. Both often require some access to the global Internet, whether to get market news, check sites like Gmail or put advertisements on Facebook.

Long a testing ground for experiments in Internet surveillance and censorship, Xinjiang is a rugged and sparsely populated region in China’s west. In 2009, the Internet in the region was shut off for almost six months after riots by the local Turkic-speaking Uighur minority and Han Chinese. Since then, clashes between the government and the Uighurs, most of whom are Muslim and make up about 40% of Xinjiang’s population, have been on the rise.

Last week, China confirmed that a Chinese citizen who was being held hostage by the Islamic State had been killed. The state news media also reported that a recent raid had killed 28 people thought to be connected to an earlier attack on a coal mine in Xinjiang.

Chinese officials have recently been more vocal in charging that the Internet is being used to spread religious extremism in the region. Human rights activists have cautioned that many in Xinjiang are being radicalized by severe restrictions on the freedoms of Uighurs, not necessarily by outsiders.

“Xinjiang is really the frontier for Internet surveillance in China because of the terrorism issue and the risk of violence,” Mr Bequelin said.

China Unicom and China Mobile, which are mobile carriers, did not respond to requests for comment. An operator for China Telecom in Xinjiang referred questions to the local cyberpolice. An official with the Urumqi municipal police said the bans affected all three of China’s state-run carriers but declined to comment further. Several complaints about the suspensions on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like microblog, appeared to have been deleted by censors late last week.

It’s unclear how many of Xinjiang’s roughly 20 million people have been affected. One of the residents whose service was shut down said that when he went to the Urumqi police station, there was a line of about 20 people, including several foreigners, waiting to ask the police to restore their mobile phone accounts.

He said he used a virtual private network to get access to Instagram, and that at the police station, an officer “took away my ID card and cellphone for a few minutes and then gave them back to me.” He added, “They told me the reason for my suspension is that I ‘used software to jump the Great Firewall.’”

He said he was told that his phone service would be suspended for three days, and added that he would no longer use virtual private networks. “It is too troublesome,” he said. “I just have to give up my Instagram from now on.”

Facebook, WhatsApp, Viber blocked ‘indefinitely’ in Bangladesh

Others said it was less clear when their phone numbers might be restored. A man who lives in the town of Yining said the police there first checked his social media postings to see whether he had written anything delicate, then said they would report his case “for further examination.”

Mr. Bequelin said the decision to suspend accounts was most likely a calculated one, given that the full shutdown of the Internet in 2009 raised hackles across ethnic lines, with some protesting Wang Lequan, the leader of the region at that time.

“The lesson from 2009 was that it was a bad idea,” he said. “You cut off the Internet, you may actually end up getting more people in the streets.”

This article originally appeared on The New York Times, a partner of The Express Tribune.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ