Remembering Dostoevsky, the sage of suffering

On the Russian literature giant’s 194th birth anniversary, we explore the redemptive quality of his bleak panoramas

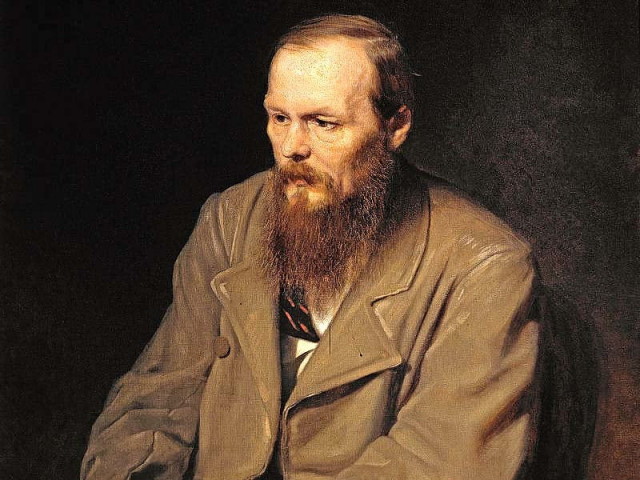

Dostoevsky is a guide who takes you to a certain elevation from where you are bound to see the world only the way he shows it. PHOTO: FILE

Enigmatic Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges tells a strange story of Kilpatrick. Those chronicling the history of this fictional personality were intrigued by how Kilpatrick’s life was a perfect example of history repeating itself. This fascination turned to wonder and later disbelief when they discovered that events in Kilpatrick’s life also seemed to mirror events in different works of Shakespeare.

Looking back at my life as a young student, I find myself a ‘Kilpatrick’ as well. The only exception is that my life seems to be imitating the works of another master - Fyodor Dostoevsky.

I first encountered Dostoevsky in an obscure corner of my father’s library. It was most likely the beginning of winter.

Heritage education: Books alone are insufficient: Alam

When I picked up the thick-looking novel – about which there was a domestic-myth that it was unreadable due to the strange names of its characters, exotic settings and antiquated printing – I saw that its front page bore image of a bearded man. It was an Urdu translation of ‘The Idiot’.

The story also began in winter. And while I could easily wrap myself up in a hot blanket, I could see Dostoevsky’s perfect man, Prince Myshkin, shivering in the cold compartment of the train bound for Saint Petersburg.

I completed the novel in eighteen days, but Dostoevsky was not quite through with me. When I put away the book, I realised that the world of Dostoevsky had seeped out of the pages and become a solid reality around me. Poverty and hunger, delirium and disease, crime and sin, disgrace and death – these were all part of this picture.

But there was something that made it appealing. Some compassionate, redeeming force. I couldn’t exactly pinpoint it then.

Power of reading : Bringing children, teachers closer to books

In the meanwhile, I entered this intriguing new world with a sense of fascination. Literature and life seemed to lose their distinction and people and characters were getting mixed up. Or rather real people had started to look like well-carved characters from a novel. Event and situation also started to imitate Dostoevsky and I began to make a mental note of how my life was prone to fateful chance meetings and how most gatherings tend to devolve into embarrassing situations or disgraceful scenes.

Was it reality or psychosis? Zoin Ansari, Dostoevsky’s exponent and the venerable litterateur who translated many of his books into Urdu, thinks that we, the people of sub-continent, can readily identify ourselves with Dostoevsky’s characters and the description of life in his novels. According to Ansari, the life in the 19th century Russia was closer to ours then the experiences presented by most western writers.

I later came up with another theory about him. I started to believe that Dostoevsky is not a writer but a ‘point-of-view’ – a guide who takes you to a certain elevation from where you are bound to see the world only the way he shows it.

Literary figure: Asif Ali Sohag remembered

You may climb down from the place or move to a different position but as long as you have the courage to stand on the steep precipice, you will continue to see that complex but fascinating panorama that we find in his novels.

Or maybe it was actually a state of mental confusion. A brain fever that many of his characters also suffered from. An ailment that consumed Ivan and Prince Myshkin and drove Raskolnikov to commit a crime. God knows better!

But whatever it was, only Dostoevsky has the power to induce it, even more than a century after his biological death.

Published in The Express Tribune, November 11th, 2015.

Like Life & Style on Facebook, follow @ETLifeandStyle on Twitter for the latest in fashion, gossip and entertainment.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ