For the last five years, my work involved putting together STEM adventures for young learners and teachers across classrooms in Norway. With balloons, beads and straws as my tools I create a learning environment which feels more like a celebration, and less like a conventional science lesson.

Children carry out real scientific experiments using balloons, beads and straws. PHOTO COURTESY SCIENCE FUSE

Children carry out real scientific experiments using balloons, beads and straws. PHOTO COURTESY SCIENCE FUSEThree years ago, I had my first opportunity to share this excitement with students in Pakistan. I partnered with my workplace in Norway to organise an interactive science workshop at the Garage School, a charitable institute based in Karachi’s Neelum Colony. My bags were filled with things one needs to blow giant soap bubbles and explode water bombs and for the next four hours, 30 children got to create, play, learn and ‘think’ like scientists. When it was over, they asked the same question: when will you be back? I learned that it didn’t matter which part of the world I was in — combining learning about science with play was equally exciting for children everywhere.If you ever happened to walk in on one of these sessions, you would most likely see students blowing up balloons to design rockets as they animatedly discuss Newton’s laws. Or perhaps hear them talk about atoms and molecules to understand how we can peel back the layers of the world. You’d also notice that unlike a traditional classroom where science education is restricted to textbooks and monologues, these sessions create an informal learning environment driven by dialogue, teamwork and most importantly, a sense of adventure.

This is how Science Fuse came to be. Most children in our country experience science as a mere collection of facts that they are made to memorise and recall during exams. They grow up thinking that science is some abstract nonsense that doesn’t have much relevance to anything they can directly see or touch. We’re also a country where science doesn’t occupy much space in popular culture (the widely prevalent emotional blackmailing by Pakistani parents to coerce their children into medical school doesn’t count). We don’t make sitcoms on science or share science jokes on Facebook, and visiting the local science museum is never on our list of fun things to do. Speaking of local science museums, would you know where to go if you had to visit the National Museum of Science and Technology in Pakistan?

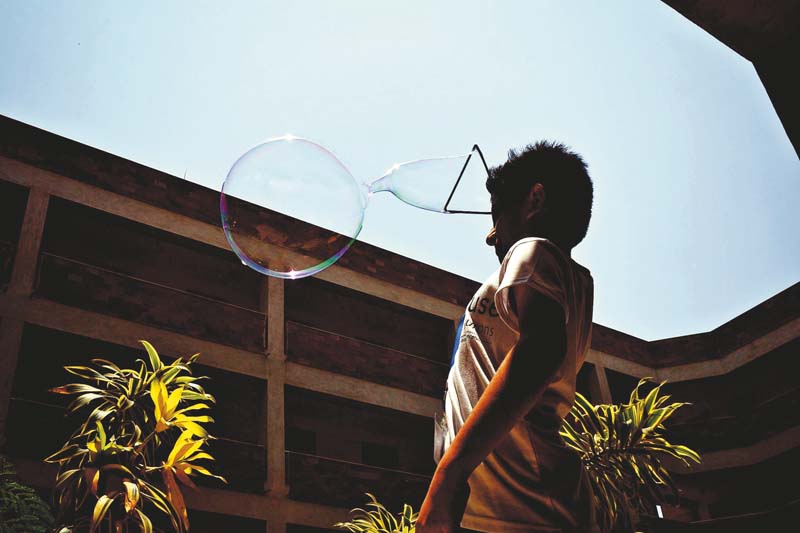

From blowing giant bubbles to exploding water bombs, Science Fuse makes science more fun for kids. PHOTO COURTESY SCIENCE FUSE

From blowing giant bubbles to exploding water bombs, Science Fuse makes science more fun for kids. PHOTO COURTESY SCIENCE FUSEThe next step was to test a full-fledged STEM learning programme and I collaborated with a leading private school in Karachi to organise a two week-long summer camp. Additionally, my team and I visited three low-income schools to conduct STEM workshops and invited their students for a week-long camp. The idea was to build a self-sustainable social enterprise that could provide quality STEM educational programmes to all children, irrespective of their socio-economic background. Our aim is to particularly engage students from public/charitable institutions to inspire them towards pursuing STEM education and careers and I learned to keep in mind the range of academic backgrounds we were dealing with.

While Pakistan doesn’t have many informal STEM learning environments, parents, educators and school administrations understand the importance of introducing and nourishing such concepts. However, a little coaxing is always required because not everyone here is equally familiar with innovative ideas being tested out around the world in the field of education.

My biggest challenge in this journey so far has been living away from my family to develop my skills. A month after getting married, I was back at work in Norway while my husband was settled in the UK. We lived like this for two years and while I was excited to be doing what I loved, I also greatly missed having a partner by my side. What makes it worth it? Seeing kids from Lyari travelling three hours by bus every day to get to our summer camp, or the text message we received from a mother who works as a cook, telling us how her son insists on becoming a scientist after attending our programme.

Recently, I worked with a young girl, Farah, from a low income family, who gave up her education due to severe discouragement from her mother. She quit her education two years ago, after finishing the 10th grade. This year, Farah worked as an assistant teacher on two of our STEM programmes. These stories — these children — keep me motivated and excited about the work Science Fuse is doing.

Make it work

Choose to invest your time and energy in building something that is impactful and meaningful to others.

Have a vision as well as a plan for how you’d like to see yourself and your project evolve over the course of time.

Value the relationships you build along the way.

Take constructive feedback into account.

Merit the value of self-learning.

Follow your heart and have fun while you’re at it.

Lala Rukh Malik is the co-founder of Science Fuse and tweets @Lrukh

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, November 1st, 2015.

1725882931-0/Tribune-Pic-(7)1725882931-0-165x106.webp)

1731756268-0/BeFunky-collage-(9)1731756268-0-165x106.webp)

1726728390-0/BeFunky-collage-(7)1726728390-0-165x106.webp)

COMMENTS (2)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ