Art review: Cutting the cord of censorship

Parrhesia II at Karachi’s Koel Gallery forces one to dig deeper within themselves and question everything around them.

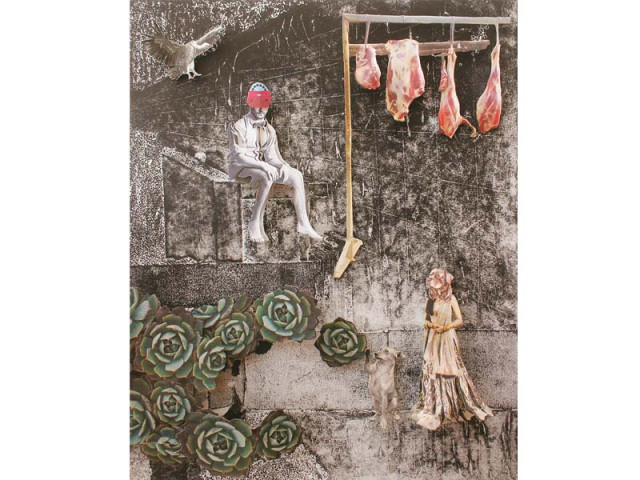

Mixed media miniature collages by Mohsin Shafi. PHOTOS COURTESY: KOEL GALLERY

Jism-o-zubaan ki maut se pehle

Bol, ke sach zinda hai ab tak

Bol, jo kuch kehna hai keh le!

Many of us are familiar with the above lines by our celebrated poet, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, about speaking one’s mind. Some of us may have also heard of 20th century French philosopher Michel Foucault, who spoke about the concept of speaking truly, freely and fearlessly: ‘parrhesia’. To Zarmeene Shah, curator of ‘Parrhesia II’ at Koel Gallery, the aforementioned concept is paramount. Despite living in a country where enforced censorship and lack of tolerance is rife, she feels the heart of this concept lies in the risk taken by any artist attempting to speak the truth, (or anyone carrying out parrhesia for that matter). Shah mentions that after all, “to do nothing at all for fear of such risks is also a kind of betrayal, even to oneself.”

Items of Reuse by Seema Nusrat.

A second part to ‘Parrhesia I’ held at Koel Gallery in 2011, ‘Parrhesia II’ includes a larger body of artists, 21, and an evolved response to the theme in accordance to rapidly changing times. Interestingly arranged, where each of the 28 pieces got their due attention, Shah cohesively put together the show in collaboration with the artists within a short span of six weeks.

Most of the artwork at the exhibition brought to mind a series of questions. Salima Hashmi’s mix media piece, Shaam, put together interesting magazine clippings and images of an assortment of shoes with the ominous text: ‘Bringing Up The Bodies’. After all, how many people in Pakistan have lost their lives unexpectedly, while their shoes lie in wait of the master who will no longer wear them?

Abdullah MI Syed’s Qaumi Tarana Chaar Hisson Mein dissected the first four words of our national anthem. It beckoned one to read, absorb and question their meaning collectively, as well as individually, and made one wonder, how many of us even know or remember the Pakistani anthem, and understand its significance?

Seema Nusrat’s delightful installation, Items of Reuse, depicted gunny bags made of jute merged with tapestries (with seemingly medieval imagery). Hanging low, these bags sprouted green grass growing from the most unexpected places. In today’s Karachi where gunny bags remind one of death and murder, does the piece depict how, symbolically, we have stepped back into the medieval era? And does the grass depict the persistence of life over death (or vice-versa)?

Give and Take by Roohi Ahmed.

Adeel uz Zafar’s work brings together imagery, sound and text — interwoven cleverly. Headphones on, the viewer could hear disturbing scraping and etching sounds as they flipped through the book, containing text and images of etched drawings (typical of Zafar’s style). One could faintly make out the words “Among the believers”, also the work’s title. Zafar seemed to ask: Are we considered faithful only if we suffer pain and go through trying experiences? Do we need to be ‘etched’ into the role of the believer? What does the term ‘believer’ mean anyway?

Roohi Ahmed’s Give and Take displayed a pair of palms, one stitched into with a red thread, and one with ripped skin after the thread was pulled out. This kind of indentation is usually deliberate and risky, and leaves ugly marks. It makes us ask, are we deliberately putting ourselves in danger, or do we have no choice?

Amir Habib’s Blind Eye was a display of blinking LED lights and images resembling the human eye and various maps. The images changed quickly, making it difficult to decipher them. Yet, the fast-paced and altering nature of this piece reminded one of the tickers on news channels, or the rapidity of news in the media.

Text Edit, a video by Hamra Abbas, cleverly used word-play to depict how commonly-used words such as ‘blast’, ‘kill’ and ‘chaos’ in today’s world have much heavier connotations. Hence, one could feel the struggle of the protagonist who kept deleting and replacing such words in an email she typed.

Mohsin Shafi’s quirky mixed media miniature collages portrayed a strange world where interesting contrasts exist: dark and light, the glamorous and the ordinary, and perhaps good and evil. Nearby, Quddus Mirza’s Kun Fayakun literally depicted sources of light in darkness (40 candles). Yet, the installation also reminded one of vigils and memorials for the dead, unfortunately so common all over the world.

While Noor Yousuf’s installation, Against Time, embodied beauty, fragility, innocence, flight and transformation, Noorjehan Bilgrami’s The Truth Remains made us question what this truth is, and how can one decipher it from the ambiguity that surrounds us?

Qaumi Tarana Chaar Hisson Mein by Abdullah MI Syed.

Other prominent artists with their works on display include Naiza Khan, Bani Abidi, Meher Afroz, Nurjahan Akhlaq, Naazish Ataullah, Imran Channa, Yaminay Chaudhri, Amin Gulgee, Shalalae Jamil, Seher Naveed and Madiha Sikander, making this show a coherent whole.

Shanzay Subzwari is an artist and art writer based in Karachi.

She tweets @ShanzaySubzwari

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, July 19th, 2015.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ