Film review: Aloha - looks are deceiving

Even with its stunning Hawaiian setting and star-studded cast, Cameron Crowe’s Aloha is an epic failure

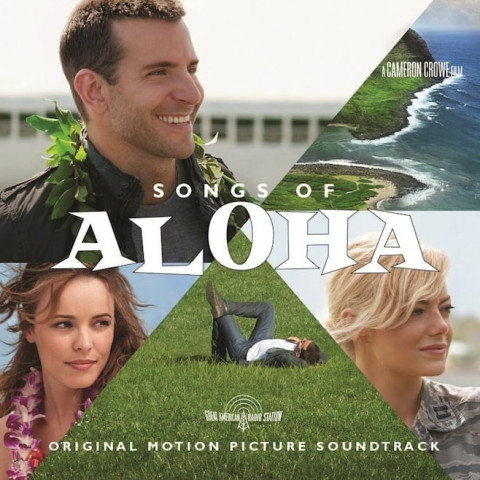

Even with its stunning Hawaiian setting star-studded cast, Cameron Crowe’s Aloha is an epic failure. PHOTO: PITCHFORK

Aloha is anything but the “love letter to Hawaii” director Crowe claims the film to be. It is not a poignant story of redemption, understanding and forgiveness that it sometimes appears to be. Nor is it an intelligent one about the life, identity and culture of Hawaii’s indigenous population. It is hardly a serious exploration of marital discord, choices and regret. And it is certainly not a powerful statement on the dangers of privatising military operations and space exploration. It is, at best, an earnest telling of a number of discordant stories lumped together, hastily and without much thought.

Aloha tells the story of Brian Gilcrest (Bradley Cooper), a former pilot with a murky past, currently working for an eccentric private defence contractor, Carson Welch (Bill Murray). Brian returns to his home state of Hawaii for a project that requires him to secure the blessings of the natives for a new pedestrian gate and to engineer the launch of a private satellite with a secret and sinister payload. The US Air Force assigns Captain Allison Ng (Emma Stone), who is one-quarter Hawaiian, to babysit and escort Brian while he is on assignment. While in Hawaii, Brian meets his former girlfriend, Tracy Woodside (Rachel McAdams), who now lives with her pilot husband, John Woodside (John Kransinski), and two children. Tracy and John’s marriage is in trouble because the latter is quiet and uncommunicative. Their marriage is further threatened by the lingering feelings Tracy and Brian have for each other. Allison and Brian soon develop a fondness for each other. This completes the improbable love quadrangle which becomes the primary subject of the film.

None of this made sense to Pascal who described the script of Aloha as “ridiculous” and wrote, “The satellite makes no sense. The gate makes no sense.” Viewers of Aloha are likely to nod in agreement as they watch the film.

The film, it is obvious, was subject to numerous re-writes, re-edits and re-dos. The transitions from one scene to the next are often abrupt and unexpected and sudden changes in camera angles during the middle of certain scenes is jarring. The dialogue is mostly clunky and seemingly incomplete. And the substance of a lot of scenes, it appears, is lost due to ruthless cutting. Complete plot points are missing from the film, thanks to heavy-handed tinkering and merciless editing. A lot has been stuffed into the film which pays little attention to tonal consistency, the development of characters and relationships and narrative coherence. The film’s 105-minute length is insufficient for the number of stories and themes Crowe wishes to tackle in Aloha.

There is obviously a lot wrong with Aloha but the film’s biggest flaw is its simplistic and superficial handling of the state’s indigenous people, their lives and their traditions. The politics of Aloha is shallow, reductive and downright phony. The reckless lack of responsibility with which the serious subject of Hawaiian statehood is handled in the film is mirrored in the makers’ decision to assign all primary roles to white Hollywood actors. Aloha uses the people and landscape of Hawaii as an exotic backdrop to tell a story of the implausible and manufactured troubles of four white people. Either way, Crowe’s whitewashing of Hawaii is reprehensible. And Aloha is a terribly boring film.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, July 12th, 2015.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ