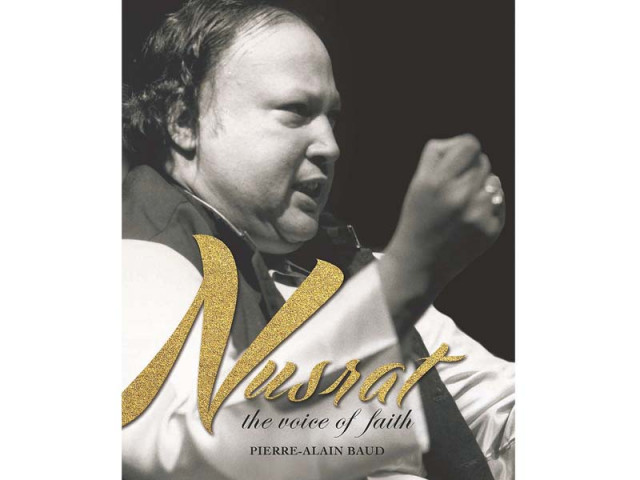

Book review: Nusrat — The Voice of Faith - A familiar composition

Pierre-Alain Baud’s latest book does make for an engaging read

Although by no means a definitive biography of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Pierre-Alain Baud’s latest book does make for an engaging read.

French author Pierre-Alain Baud’s Nusrat — The Voice of Faith is the latest biography of the giant of qawwali. Since much of Khan’s life has already been told in great detail, there are not a lot of things that will qualify as new or exclusive for avid fans. However, the book is not meant to serve as an exhaustive encyclopedia on the man; yet, it does share some interesting anecdotes that dotted Khan’s illustrious career. For example, his first concert in Brazil was such a colossal failure that Khan almost decided not to perform the next day. Fortunately, he changed his mind and the performance at a packed hall in Sao Paulo was a roaring success.

Baud, who spent a significant amount of time in Khan’s company, opens the book with a couple of chapters dedicated to Pakistan and qawwali. This serves as an effective prelude because the book is clearly written for an international audience (the French in particular). Translated later into English and Urdu, Baud’s book aims to first acclimatise the reader to the South Asian art form, then to its constituents and, finally, to its curators. This part of the book also highlights some fascinating developments in the timeline of qawwali’s ascent to pop culture, such as its first depiction in film in the 30s. In 1945, the film Zeenat featured a qawwal party led by three women, including the Queen of Melody Noor Jehan. Moreover, the book features interesting blurbs on world music label Womad Records and the Theatre de la Ville in Paris, where Khan performed as many as 16 times.

Other facts, those pertaining to Khan in particular, are well-known. It is often narrated how Khan’s father and acclaimed qawwal Fateh Ali Khan wanted his son to become a doctor as he believed his own profession did not warrant an enviable status in society. Thus, Baud does well to cite other texts, such as Ahmad Aqeel Ruby’s poetic take on the scenario: “He (Khan) would rather apply the balm of music to the wounded hearts of his listeners who suffered the pangs of separation from their loved ones.”

The book, therefore, is by no means a definitive guide on Khan or qawwali, but it makes for an engaging read on a hot summer afternoon, especially for those who just can’t get enough of the man who serenaded our souls.

Ali Haider Habib is a senior subeditor at The Express Tribune’s magazine desk.

He tweets @haiderhabib

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, July 5th, 2015.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ