The water crisis and the need for social accountability

This approach aims to facilitate constructive civic engagement.

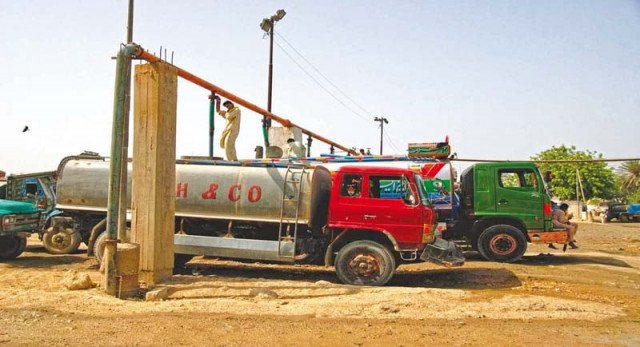

Men fill water tankers from a connection in Karachi. The city’s water crisis has worsened recently, leaving many of the residents dependent upon services such as these tankers. PHOTO COURTESY: FARHAN ANWAR

One of the best ways to plan effectively to redress public grievances about civic services is to carefully assess the needs, gaps and potentials in service delivery and subsequently incorporate the feedback in the policymaking and planning process. Implementation of social accountability tools can serve as a viable mechanism to ensure that demand data is documented. This approach aims to facilitate constructive civic engagement.

Social accountability tools

Examples of social accountability tools include citizen report cards, social audits, citizen charters, right to information acts and community scorecards. A few years ago, an encouraging step was taken by the city's sole public sector water utility — the Karachi Water and Sewerage Board (KWSB) — to seek consumer feedback on their services by utilising the Citizen Report Card (CRC). This initiative came in the wake of deteriorating services, weakened community interfaces and poor revenue generation.

The CRC, pioneered by the Public Affairs Centre (PAC) in Bengaluru, India, is a simple yet powerful tool to give civic agencies systematic feedback from their users. It gains this feedback through sample surveys on the aspects of service quality, enabling public agencies to identify the strengths and weaknesses in their work.

KWSB's study

A total of 4,500 households were interviewed across nine towns in Karachi. The questionnaire covered all the aspects of their services — water availability, quality, frequency of supply, coping mechanisms for water scarcity and modes of public engagement with service providers to resolve their complaints.

For example, the respondents were asked about their experiences during the last year when they were faced with low or lack of water supply lasting for five days or longer. It was reported that people were then forced to resort to expensive sources of water. Around 31.3 per cent availed vendors in the form of tankers, 16.3 per cent relied on illegal connections from the mains and 15 per cent resorted to bottled or canned water during the months of water scarcity.

A disconcerting discovery was that of all the respondents, 37 per cent — over a third — of all mains users were reportedly using illegal means to access water. Illegal connections from the mains line was found to be a frequently occurring trend in Gadap, Saddar, and SITE. Nearly half of Saddar's population — 49 per cent — was found to rely on illegal connections from the mains line, while the other half obtained its water through vendors, boreholes and legal connections from the mains.

The verdict

About 40 per cent of the households who faced some kind of a problem with water supply never interacted with the authorities. Instead, political representatives were most commonly approached. An interesting and disturbing finding was that 60 per cent of the lowest socio-economic group never complained. Interactions with KWSB officials were extremely low in most towns — over 26 per cent of the households in the nine towns did not think it would make any difference, while over 19 per cent did not know where and with whom they were supposed to interact. Around 79 per cent of the issues were related to water stoppages, and a majority preferred complaining in person. Meanwhile, over 47 per cent of the households who had approached the KWSB found its officials very inaccessible.

This was a highly commendable initiative undertaken by the KWSB by opening themselves to this kind of public scrutiny. However, it has been now been five years since this CRC was conducted and such social accountability tools can only produce the desired dividends if they are conducted regularly.

In the intervening periods, the data collected has to be evaluated and performance improvement plans based on it have to be undertaken to remove the shortcomings indicated. It is high time that the KWSB revisits the process and institutionalises it to facilitate long-term improvements.

The writer is an urban planner and runs a non-profit organisation based in Karachi city focusing on urban

sustainability issues

Published in The Express Tribune, May 18th, 2015.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ