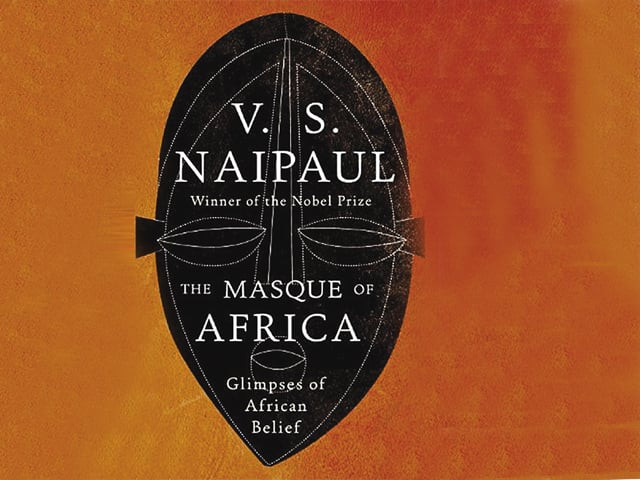

The Masque of Africa: In the dark

In The Masque of Africa, Nobel laureate VS Naipaul dons his misanthrope’s hat, questioning everyone, sparing no one.

Ultimately, Naipaul’s travel writing is as unlike his brilliantly original comic novels as can be. There is a weighty gravitas to it, and far less humour — in the current state of humanity and its belief systems, he finds little to laugh at. In his essays and interviews, he clearly delights in his often outrageous, rightwing opinions and perhaps even more so in his critics’ dismayed reactions to them. And yet, his caustic, prescient reportage has always been far more than just hackwork. After all, it vaulted him to international recognition in the 1970s and 1980s with books such as An Area of Darkness, India: A Wounded Civilisation and Among the Believers.

In Africa, Naipaul focuses his characteristically narrow lens on the remains of pre-colonial religious belief in the countries through which he travels, comparing local rites and rituals with the more recent effects of Christianity and Islam. His “characters” range from witch doctors and soothsayers to well-heeled entrepreneurs. As he journeys from shrines to tombs and attends portentous rituals and ceremonies, he asks what role pagan belief systems still play in their lives. He concludes that the old ways better expressed the spirit of Africa’s indigenous peoples and were vital to Africa’s being.

So what does Naipaul see in modern Africa? Foremost, a distinct lack of individuality: “It is hard to arrive at a human understanding of the pygmies, to see them as individuals. Perhaps they weren’t.” Elsewhere: “And moving in this way from one set of ideas to another, you came to a feeling that its politics and history had conspired to make the people of South Africa simple.”

At points, his writing is apt to slacken; dull clichés dot the landscape. Having written once that Colonel Gaddafi is expected in Kampala to open a mosque, he repeats the information a few pages later. Similarly, the symbolic qualities of bark-cloth are reiterated several times, as is the fact that his driver in Ghana is of Danish descent. A good editor could have tightened the prose.

In the midst of rambling (and sometimes dull) anecdotal history, there are rare glimpses of the old Naipaul. His gimlet eye notes that in Uganda, men slip magic herbs in their wallets to protect their money. In Ghana, he etches a vivid portrait of former president Jerry Rawlings, who leans over and touches his knee when he wants to make a point. In Nigeria, he captures the mad anarchy of Lagos airport. But these instances are unusual, ironically, for a writer whose previous reportage is worth less for its gloomy prognostications than for his eye for minute detail.

Naipaul’s argument is that Africa, left to itself and its pagan beliefs “might have arrived at its own more valuable synthesis of old and new.” What drives his doleful peregrinations is not this thesis, it is the sense of the journey itself: stale hotel rooms and the dust and flies are as interesting to him as local shrines and small gods. For his readers, that, perhaps, is the saving grace of this book.

Published in The Express Tribune, November 28th, 2010.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ