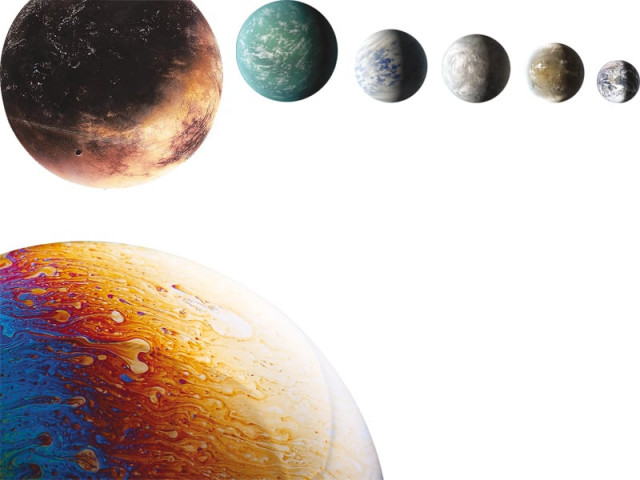

Milky Way: Planet plethora

NASA's Kepler mission announces a planet bonanza.

A latest announcement by NASA confirms the detection of 715 new planets orbiting 305 stars. These planets have been detected by NASA’s Kepler space telescope using a technique called the Transit Method: if a planet comes in front of a star, then the light from the star will dim a little and there will be more than one dimming if there is more than one planet. This works, however, only for those systems that have an edge-on orientation from our perspective. Similarly, astronomers can also estimate the size of a planet by the level of dimming — a larger planet will result in a larger dimming.

The significance of the recent announcement is that close to a hundred of these newly discovered worlds are comparable to Earth in size, and almost all of them are smaller than Neptune — one of the gaseous planets in our own solar system. And the reason why we care about finding planets that resemble the Earth is that those might be the worlds teeming with life.

The histogram shows the number of planets by size for all known exoplanets. The blue bars on the histogram represent all the exoplanets known by size before the Kepler Planet Bonanza announcement on Feb 26, 2014. The gold bars on the histogram represent Kepler’s newly verified planets.

Indeed, four newly discovered planets orbit their stars at a distance where water can stay in liquid form. This distance is called Habitable Zone. In our own solar system, Earth is in the middle of it, but Mars and Venus are, in some estimates, also at the edge of the habitable zone of the Sun.

But even in the habitable zone, the worlds may still be fascinatingly strange. For example, Kepler 296f is one of the four new planets orbiting in the habitable zone of its star. The planet, however, is twice the size of the Earth. Our own solar system does not host any bodies of that size. For that reason we don’t know if Kepler 296f is a rocky planet like the Earth or a gaseous planet like Neptune. Furthermore, the host star of Kepler 296f contains only half the mass of our sun and thus is a bit cooler than our own host star. The only thing we can say with certainty about Kepler 296f is that it will be a strange world.

But why should we care about worlds that are tens or hundreds of light years away? Apart from the satisfaction of basic curiosity that drives humans and our sciences, the discovery of new worlds brings us closer to answering one of the fundamental questions of humanity: are we alone in the universe? Given that there are more than a hundred trillion stars in the universe, the answer has to be ‘no’. But we don’t have any evidence yet.

The discovery of planets around other stars brings this search for life one step closer. We don’t know if any of these 1,700 planets are inhabited. But considering the abundance of material in the universe that makes up life — carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen — and the tendency of life to thrive on Earth even in extreme hot and cold conditions, I would place my bet on several of these worlds to be inhabited by some forms of life. Life may be different — but life it will be!

IMAGE CREDIT: NASA AMES/W STENZEL

Salman Hameed is associate professor of integrated science and humanities at Hampshire College, Massachusetts, USA. He runs the blog Irtiqa at irtiqa-blog.com

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, July 13th, 2014.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ