Church attacks - II : Echoes of a silent exodus

As people continue to leave Peshawar, they take a part of the city with them.

Daniel’s family’s presence in Peshawar predates the creation of Pakistan, but for Daniel himself the search for identity is far from over. And so after spending 32 years of his life here, he is now looking for another home, in a place where he can satisfy the fundamental human need to belong.

The impact of the suicide blasts at the All Saints Church will probably take decades to slip into history. The social fabric has been torn to shreds most ruthlessly and any sense of oneness different religious groups may have felt in this city is now little more than absent sentiments. People born and raised here question their existence more frequently, more vociferously, than they ever did.

“Everyone wants to leave now,” said Daniel. “I have also applied for asylum. I was born here but now I am ready to go anywhere. Malaysia, Australia, United Kingdom...anywhere.”

Two months after the bombings, in November last year, Shaan* and his family also applied for asylum to the UK. There is much desperation in his voice when he talks about leaving. Shaan wants this city to only be in his memory. He makes the six-month wait sound like years. “They keep assuring us that the visas will be sent soon but nothing has happened as yet,” he said. “Non-Muslims haven’t been treated well in Pakistan for a long time, but after the blasts we thought we should just leave.”

Fears seem both imagined and real. He constantly speaks of a “they” who are against religious minorities. “They will take everything away from us; they are occupying our schools and colleges; we need to make our arrangements before they take over everything.”

In their desperate need to escape, little thought has been given to what this new life will hold for them. Shaan has no idea what he will do in the UK, but he is convinced he will do “something.” And he’s sure that ‘something’ will be better than anything in his own country.

The desire for a safer, more respected life transcends particular income groups and class backgrounds. Younus* works at a very senior position at a company in Peshawar and he too, is packing his bags for a country in Europe. He is the second generation of Pakistani Christians living in the city. Younus says he has seen too much in the past few months. “I have grown up here and seen the good days, but now there are too many security threats, there is increasing discrimination and marginalisation in society. I can’t raise my children here. They won’t be able to survive,” he said.

Scanned copy of a letter requesting asylum

Most people, however, are too afraid to even publicly acknowledge that they want to emigrate. It takes weeks of repeated calls and countless assurances and promises that identities will not be disclosed for people to simply confirm that they have indeed applied for asylum.

Friends and family of Joseph* and Brandon* say they were sent back from Sri Lanka for not having legal documents to travel further. It’s not clear what the final destination was, but Joseph says the trip was only a vacation. “I have no reason to leave Pakistan, I have a good life here and a great job at a multinational company,” Joseph said, without specifying where he is employed and switching off his phone.

For some the pursuit of happiness has also become irrelevant. Diocese of Peshawar Provincial Youth Coordinator Insar Gauhar had two children, both of whom died on the spot. All the memories of his boy and girl are associated with Peshawar and there is no way he can let himself leave that behind. The children’s school bags still lie around, their clothes are neatly stacked. “I would think about leaving sometimes but I don’t anymore. My son and daughter are buried here.”

His wife was also critically injured in the attacks. In their battle to recover from the physical and emotional injuries, they have found solace in religion. Gauhar is part of the religious counselling programme and visits survivors at their homes, promising them the comforts of faith and a better hereafter.

There are no clear answers with respect to how many people have left Pakistan following the blasts or how many have applied for asylum. The answer most residents give to this is “many.”

Bishop Humphrey S. Peters, however, says there are no additions to the number of people wanting to emigrate. “There are Christians here who want to leave but that’s true for all of Pakistan.” He does agree though that the situation in Peshawar is worsening and the level of persecution increasing. Bishop Humphrey is a controversial man here. Some people allege he only gives asylum documents to his relatives and friends, leading to strong resentment within the community against the church leader.

Community representatives at the All Saints Church also insist nothing has changed and that in fact “no one” has wanted to emigrate after the suicide bombings that killed nearly 105 people and injured more than 250, according to figures of the Diocese of Peshawar. There is a very strong, sometimes almost aggressive, defence when migration is mentioned.

“We keep reading in newspapers that we are scared and leaving the country, but nobody is going anywhere because of this particular incident,” said Pastor Fayyaz Channa vehemently.

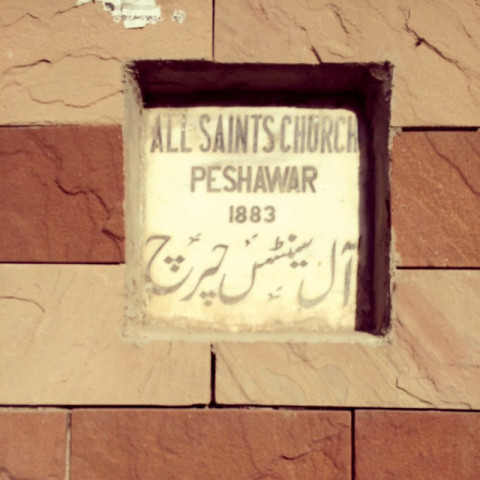

But the sense of fear is palpable at the church itself. The church, which opened its gates in 1883, no longer has its doors open for all worshipers. Barbed wire encircles the boundary walls and a noticeably anxious policeman stands outside. Identification is thoroughly checked before worshippers walk in, and a biometric identification system is being installed.

A senior member of the church committee, Javed Iqbal, says regardless of what happens, he will live in Pakistan. “Even if we have to live hungry, fate has put us here. It is the will of God that we were born here.”

And yet, there is still a presumably subconscious but clearly desperate need to be recognised as Pakistani. Despite the tragedy that has hit them, or perhaps because of it, they reiterate, even when not asked, that Peshawar is their city, Pakistan is their home.

“We are Pakistanis, we are Christians, this is where we have to live and die,” said the pastor.

“We can’t leave our country, our city, our church. I was born in this city...We are Pakistanis. My father, my grandfather...they were all associated with this church,” Iqbal added.

But the church is no longer the same house of worship his ancestors left behind. Intricate woodwork and stained glass windows dating back to the 1800s have suffered irreparable damage. “We could not find anyone to repair the wooden panels, everybody said the patterns were too detailed and this type of work cannot be replicated,” said Pastor Channa. There was one carpenter in Gujranwala who managed to fix the wooden frames behind the pulpit.

The men speak on a Monday morning in the courtyard of the church. Behind them is a wall with shrapnel marks a few inches deep. It’s the wall of the Sunday school from where children were stepping out when the explosions occurred. In a terrible twist of fate, the children died when they were going downstairs for a thanksgiving lunch. To the left of Channa and Iqbal is a burnt down tree that bears another testament to the enormous loss this church has had to bear in minutes.

The damage is irreversible in many ways. The void left in one day will take many years to fill. Survivors recount the loss of their best students, doctors and teachers, again and again. They talk about medical student Noel Williams, teachers and sisters Zaresh and Samreen, among other young, bright adults who had attained academic or professional excellence. It’s as if a group of people have been successfully and systematically wiped out, and with them an entire society fragmented. “Our community has been pushed back by at least 50 years because of this incident,” Iqbal said.

Religion and sect is nearly always identified when rescue and rehabilitation efforts are talked about. Iqbal and Channa frequently mention the “Muslim brothers” who helped them in their time of need. Minutes into the conversation, the word Muslim is replaced by Shia.

“Most people living around the church are Shias and they understand our situation because they are also targeted. They sent us food for three days after the attacks. I feel like they are the true protectors of the church as opposed to the police,” Iqbal said, adding “shopkeepers sent yards of cloth to cover the bare bodies of the dead and injured after the blasts occurred.”

Despite these humanitarian gestures of solidarity, it is clear that the space for co-existence is fast reducing and for many people the time has come to leave.

And as people continue to leave, they take a part of the city with them. The Sikh shopkeepers, Christian missionaries and Hindu traders are now either etched in the city’s memory or are a part of beautiful buildings that precede Partition and still seem determined to tell the story of the city that once was. But even in some of these buildings now, there are deep, piercing holes and a burnt down tree.

*Names have been changed to protect identity Photos: Tooba Masood/Express

Published in The Express Tribune, June 2nd, 2014.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ