A corny affair: Kohistan’s maize cultivation reliant on old-fashioned means

Unlike the rest of Hazara, the district starts sowing as soon as snow clears by the end of April.

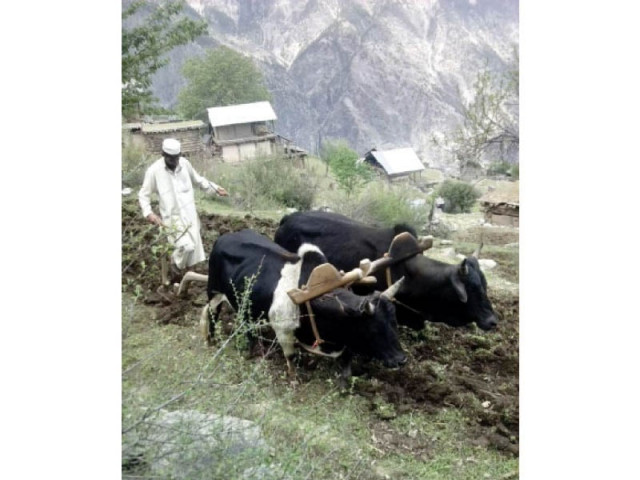

A pair of oxen plows the land to prepare it for cultivation. PHOTO: EXPRESS

Maize or corn is a staple crop of Kohistan. Located in a remote hilly area, the district does not produce much of vegetables or wheat, making maize the go-to food source for residents.

In the rest of Hazara division, sowing usually starts after May 15 but Kohistan has a different agricultural pattern. As soon as snow starts to clear around the end of April, farmers start sowing the cereal using primitive methods of cultivation.

According to the agriculture department, Kohistan grows maize on 26.40 hectares which yields 111.65 kilogrammes (kg) per capita annually. The district produces 5.38% of the total production in the province.

In comparison, Kohistan yields 10.58kg of wheat per capita and 1.54kg of vegetables per capita.

The cycle of corn

From sowing till harvesting, the process involves several festivities and traditional events, land owner Shamsur Rehman told The Express Tribune.

During the season, dozens of oxen are seen plowing the land, said Rehman. He said a pair of oxen is called wargoee in Shina, the language spoken in Kohistan. Wargoee are then attached to a large wooden piece which holds a blade plow.

Giving the field two weeks for germination, farmers then start badoor – an exercise which makes the maize plant stand straight so it grows to the required length.

The next stage is weeding. Farmers, women and children purge their crops of weed, a process locally known as naind. The weed is then used to feed their livestock. Over the time period in which the crop ripens, farmers add organic manure, called dheraan, twice. This exercise helps get maximum yield.

Of the cob

After three months, the farmers harvest the maize when the sheaths dry. Locally known as sheesh, the cobs from the harvest are put in a place called the khol and exposed to sunlight for a few days. The farmer then invites the hashar, a group of villagers consisting of mostly young men, to separate the grain from the cob. These men or hashirs come equipped with long clubs which they will use to beat the corn to separate the grain.

According to Saeed, from Dasu, around 20-25 well-built men ‘compete’ by hitting the sheeshon dehri (pile of cobs) to separate the grain. During the shelling process, the chant slogans of ‘ha hoey ha kar - chat kar chat kar’.

The one who strikes the club with most force establishes himself as the most powerful man.

After grains are separated, the volunteers are rewarded with desi ghee parathas and dry fruits.

The leftover cob is used as fodder for livestock, ensuring nothing goes to waste.

A sorry state

With no access to proper roads, Kohistan district gives off an air of neglect. The area still uses the farming techniques of a bygone era, deprived of basics like tractors and threshers.

“We are still the inhabitants of a stone age. We have no machinery or road access to our land,” said Abdul Hadi, a farmer in Chawai village. He said despite being rich in resources, Kohistan has failed to attract the attention of local leaders who could try and improve the living standards of residents.

Published in The Express Tribune, May 11th, 2014.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ