Why are PPP governments violent for Karachi?

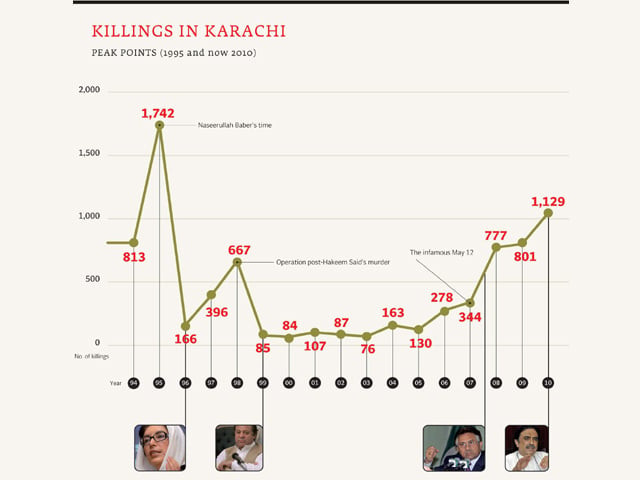

The only other time violence was this high was in 1995 during Benazir Bhutto’s second tenure.

Why are PPP governments violent for Karachi?

The statistics are incontrovertible ‘proof’. This year the number is 1,100. The only other time it was this high was in 1995 during Benazir Bhutto’s second tenure. But in our desperation to extrapolate, we must not frivolously affix blame.

Then and now

Afzal Shigri was the inspector general of the Sindh police force between the years 1993 and 1995. He describes his experience of being at the helm of affairs of the law-enforcement agency at that time as “the most difficult time of my life”. By the end of his tenure, the number for Karachi hit 1,742 — double from year before with 813. This was when the PPP didn’t have any coalition partners in the Sindh government.

“Many of my men were killed during those two years,” Shigri recalls, adding that one of the main challenges he faced was keeping the morale of his forces intact. “There were no-go areas in the city where the police acted as a buffer between two parties who were battling it out with heavy arms in the streets.”

This much was the overwhelming memory of analyst Zahid Hussain, who was a reporter for the monthly Newsline in the nineties. He also says that back then the battle lines had been drawn between the PPP government and the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM). “There were also gun battles between the MQM and Haqiqi groups.”

In reaction, the authorities launched an operation against the militant wings of political parties. But what former IG Shigri doesn’t recall, however, was that the law-enforcement agencies were also accused of carrying out extra-judicial killings. Nawaz Sharif initiated a crackdown — the brunt of which the MQM came to face. But it was after Bhutto came to power for a second time (Oct 1993) that it gained force under the command of former army general Naseerullah Baber who became notorious for backing the off-the-record murders.

Thousands of activists belonging to the MQM and its student wing the APMSO were arrested. Many of them were killed in encounters with the police, Rangers and the then pro-establishment party, the Mohajir Qaumi Movement-Haqiqi.

According to Shigri, the difference between the killings then and now is that in the 90s there were ‘clashes’ where political supporters in one neighbourhood would open fire on their rivals in the next neighborhood for days on end. “Now we have target killings in which the murderers sneak past the law-enforcers and kill people within minutes and then disappear.”

Analyst Zahid Hussain agrees to this extent that target killings have increased in these times. “But remember that it happened in 1994 and 1995 also and there were many cases of young men being found in gunny bags with gunshot wounds.”

Shigri adds that the mess Karachi is in today is the worst of the violence and has its roots in the 1990s. “Today, apart from politically motivated killings, we have sectarian murders and also the Taliban-backed militants who are [acting up] in Karachi.”

For Hussain, the ‘turf war’ today is now more complex given that there has been a rapid change in the ethnic composition of the city. For example, the Pakhtun-supported Awami National Party didn’t enjoy a power base as it does today as a result of the influx of families from the northern areas.

Pressures

Police officials say that whenever they round up suspects with political backing involved in target killings, there is tremendous pressure to release them. A former capital city police officer, who wishes to stay anonymous, says, “the problem is that many criminals have taken refuge in political parties. Also, each of these parties has a militant wing”.

He says that even when the police apprehend the murderers involved in target killings, the political parties backing them ensure that they are taken care of and bail them out one way or the way. Although the former CCPO refuses to admit that he had to release such people during his tenure, he says if they don’t, “they get their people released through the courts.”

Shigri says the pressure is not only from political parties. In fact, all influential segments of society, including business groups, also apply pressure.

Operation

A senior police official of the Anti-Violent Crime Cell says that his experience shows that violence in the city comes under control following a concerted crackdown. He gives the example of the era of the early 1990s that was a period of political killings. But when asked if the same formula would work in comparison today, he answers by saying that his force is facing a complicated situation in which ethnic, political and sectarian groups are all involved in the bloodletting, and in many ways overlap with each other. The question really is, he says, whether we can launch an operation against all of these groups at the same time. “I don’t think that anyone is in a position to do something like that.”

Published in The Express Tribune, October 24th, 2010.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ