Conserving heritage: Architects hit a wall while restoring walled cities

Reconstruction projects in inner cities of Lahore, Multan had some success stories, some failed attempts.

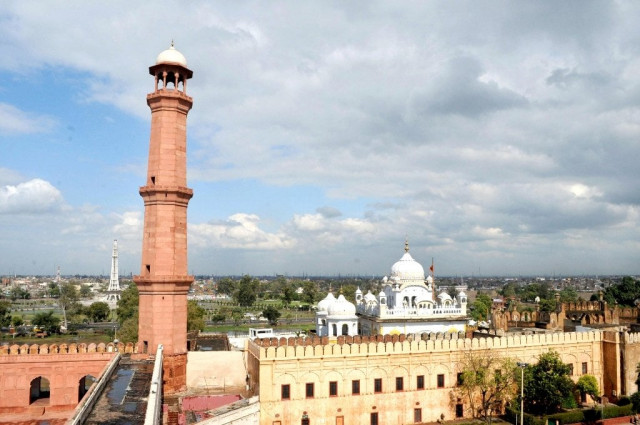

Reconstruction projects in inner cities of Lahore, Multan had some success stories, some failed attempts. PHOTO: FILE

“Pakistan’s rich culture is one of the country’s best kept secrets,” said architect and urban designer Shahnaz Arshad. To unravel this secret, she led a project to ‘revitalise’ the Walled City of Lahore.

The Old City was a labyrinth of opulence, heritage and culture. But over time, many people who did economically well left the Old City, leaving behind a population that was poor and marginalised, explained Arshad at the third day of the South Asian Cities Conference in Karachi. Many of the buildings in the inner historical city were taken over by commercial activity and warehousing, causing Punjab to “lose its valuable historical stock”.

With the dilapidating state of the city, architects recognised that “our cultural heritage assets need to be restored, conserved and put to adaptive reuse”. Arshad, under a project supported by the World Bank, the Aga Khan Trust for Culture and the Punjab government, began the restoration of the “Shahi Guzargah” or the “Royal Trail” – starting from the Delhi Gate to the Lahore Fort.

The reconstruction project began, but the biggest and foremost challenge was emptying the encroached public spaces Arshad told the audience. “Entire facades of the monuments were covered by markets that had sprawled in the city over the years.” Getting rid of them was a “long, consultative and negotiated process”.

This is where the integral part of the reconstruction process came in: engaging the local public and residents. The reconstruction project involved the local community and increased owner equity participation. The residents volunteered and contributed to 5per cent in 2011 and 15per cent in 2012 of the cost. Some of the markets were relocated and the facades were restored and strengthened so that they could support the new infrastructure.

“However, urban reconstruction in historical contexts is difficult,” Arshad grimly said. And no one has patience, she added. A lot more needs to be done and the reconstruction needs to be sustained.

This problem is reflected in Fauzia Qureshi’s presentation of a similar project in the Walled City of Multan.

Qureshi, also an architect and the former principal of the National College of Arts, Lahore, who had some success stories of reconstruction the major monuments of the inner city of Multan. Her consultancy provided surveys, data and restoration plans of the tombs of Shah Rukn-e-Alam, his mother, Shah Sabzwari, the Eid Gah Mosque, and other temples, shrines, mausoleums and dharamshalas. Many of them were reconstructed and restored.

However, some plans of the reconstructions did not last. The Damdama is a part of the Multan Fort wall and occupies north-western corner of it. It is the highest point of the fort, and Qureshi showed a picture with a Union Jack hoisted on it – after the British defeated the Sikhs in the mid-nineteenth century.

Despite, Qureshi’s team telling the government that the Damdama only had a few leakages and cracks that “needed to be stitched up”, the government decided to take it down and build a restaurant instead.

She also narrated how she was successful in removing Gol Market that had encroached on public just outside the Multan Fort. The government was asked to build a green roundabout and other green belts going towards the fort. “But, two years after the area was cleared, a mosque was built on the roundabout itself.” Some markets also returned, she sighed.

Published in The Express Tribune, January 13th, 2014.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ