Analysis: Comical versus outrageous

Statements by JI and JUI-F reflect a reach for the extreme right – manifested in increasing anti-Americanism.

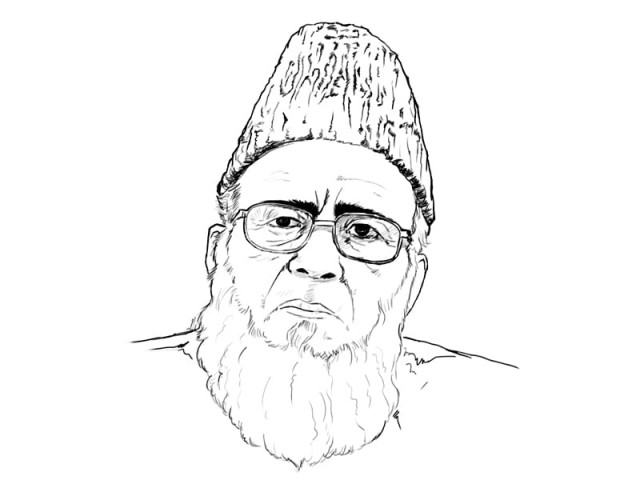

The chief of the very same JI whose last leader termed the TTP’s struggle against the Pakistani forces ‘un-Islamic’, now says the TTP militants are martyrs and the Pakistani security forces are not. DESIGN: JAMAL KHURSHID

The recent controversies created by the debate on ‘martyrs’ (shaheeds) is reflective of a deeper existential struggle within the religio-political parties of Pakistan – one that is deeply disturbing and potentially dangerous.

The two statements that have stood out in recent days have been given by Maulana Fazlur Rehman of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI-F) and Syed Munawar Hassan of Jamaat-e-Islami (JI). Both are the chiefs of their parties which are considered mainstream religio-political groups.

Mainstream?

The JI and JUI-F are considered ‘mainstream’ because, though religious in nature, they incorporate certain political correctness and realities into their agenda – however minimally that may be. This ensures that they remain close enough to the centre of the political spectrum, which is where politically viable options are located when it comes to electoral contests, and right enough to appeal to a particular base. It is a delicate balancing act.

Also, though they have never been the largest parties of the country at any point in time, mainstream religio-political parties were basically the only group representation of the religious right in national institutions such as parliament, where they acted as a sort of political filter for extremist ideology. Groups espousing radical ideology (on both the left and the right) are usually on the fringes and only serve as external pressure groups outside the mainstream. Like them or not, this was a key function in a country where religious sentiment runs higher than most – and that too on whim.

There is no doubt that mainstream religio-political parties have long held ties with the extreme right or left, call on them for support for their political campaigns and protests, and, in many cases, even have members that hold such extreme views. But, historically, that is the extent of such collaboration. There are exceptions, of course, such as the involvement of some mainstream political parties in the sad history of East Pakistan and the provision of sanctuary to al Qaeda leaders post 9/11. But these are usually exceptions, not the norm.

As for their politics, since entering the mainstream in Pakistan, the JI has, from time to time, come up with controversial statements – but often they foray into the extreme fringe, solely for the purpose of shoring up its credentials as the ideological leader of the political right. Maulana Maududi’s version of social justice politics based on Islam is saluted but his sceptical view of the formation of Pakistan is avoided. In fact, over time, the JI’s ideological politics became an important part of the religio-nationalism adopted by Pakistan’s main institutions, such as the all-powerful army’s ‘Jihad Fi Sabhilillah’, to provide a binding force to the country in the form of religion during and after the tragedy of East Pakistan. That is just practical politics.

Qazi’s politics

Under their previous chief, Qazi Hussain Ahmed, JI’s religious conservatism moved more towards practical politics than it had ever been. Ahmed became chief of the party at an important time: when the anti-Soviet jihad was drawing to a close. The JI, besides a handful of other political parties, was a key link between the concept of jihad, martyrdom and mainstream politics in Pakistan – a link that was fostered to good effect by Ahmed during his over two decades as chief of the JI and the security establishment. The link was also important to turn the political narrative when the time came. Under him, JI’s conservatism was a barrier between political religion and violent extremism.

Most recently, in the heat of battle between Pakistan’s security state and the Pakistan-based extremists, Ahmed had gone as far as to say that while the Afghan Taliban’s resistance against US-led coalition forces in Afghanistan is true jihad, that of the Pakistani Taliban in Pakistan is un-Islamic. That’s quote-unquote. Ahmed was subsequently targeted by the Pakistani Taliban led by Hakimullah Mehsud in a suicide bombing (which he managed to survive).

Radicalisation of the right?

But the trend has changed; what was once an occasional opportunist foray into the extreme right by religio-political parties now seems to have become an ideological habitation.

This change manifests itself most blatantly in the case of the JI, who recently lost two old masters of this game in Qazi Hussain Ahmed and Prof Ghafoor Ahmed. The chief of the very same JI whose last leader termed the TTP’s struggle against the Pakistani forces ‘un-Islamic’, now says the TTP militants are martyrs and the Pakistani security forces are not. This is not the first blatantly tactless statement he has given: There are others on rape and associated social ills that reflect a reversion towards extreme obscurantist ideology.

His statement on martyrdom came a few days after JUI-F chief Maulana Fazlur Rehman said that even a dog killed by the US is a martyr. He is also among those religio-political leaders that are considered politically mainstream – those who issue the occasional fatwa, and endorse the occasional outlandish statement, but whose raison d’etre has mainly been to remain the link between the ‘ideals’ of religious nationalism and the practicality of Pakistan’s politics and international relations.

While Rehman’s statement on the martyrdom of canines is more comical than Hassan’s demoting of Pakistan’s armed forces, both statements equally reflect a reach for the extreme right –particularly manifested in increasingly anti-Americanism in the face of drones and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

This reach is a product of the times. Firstly, the far right has, over the last few years, moved further right than it has ever been, fuelled by more and more grandiose conspiracy theories and increasing violence in Muslim countries (this argument can be further extended to society writ large). The extreme right in Pakistan has also started, perhaps for the first time, to indulge in mainstream politics – as is the case with the extremist Sipah-e-Sahaba’s political form of Ahle Sunnat-wal-Jamaat (ASWJ) that contested and won many votes in South Punjab and nearly won a seat in Karachi. Other extremist leaders are also beginning to get involved directly in electoral politics now more than ever.

On one hand, these mainstream religious parties have to reach out to remain in touch with that move to the right. On the other hand, and this is more important, the traditional role of these parties as the link between religious nationalism and practical politics has been challenged and occupied by a new party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI) – a newer and shinier party led by a charismatic national icon; a party that is more attuned and relevant to the times (and even they are being pulled right).

In both cases, mainstream religio-political parties are being pushed and pulled to the right, and the outrageous comments on martyrdom are simply a desperate effort to remain relevant. The delicate balancing act is no more.

Parties struggling in terms of electoral politics usually resort to extreme measures. But this overreach by the religio-political parties, and their fellow rightwingers, comes at a time that the country is on shaky ground internally, regionally and internationally. It is now a survival act that threatens to fuel Pakistan’s greatest malaise: extremism, intolerance and hatred.

This trend could also translate into the deepening of Pakistan’s religio-political right, further polarising the country and further radicalising the small, but not ignorable, support base of the religio-political parties. Even if a majority of their support stops supporting them, it brings radical narrative into the mainstream and the mainstream towards radical narratives. It sets the bar higher, or, as the case may be, lower. Above all, it means that the balancing act, that traditional filter between Pakistan’s extreme fringe and the mainstream, is no longer working – threatening to asphyxiate the country in an environment of toxic hate and violence.

Will Pakistanis who lose their lives as a result be worthy of being called Shaheed, Mr Hassan?

Published in The Express Tribune, November 12th, 2013.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ