“The past is weird. I mean, does it really exist? It feels like it exists, but where is it? And if it did exist but doesn’t now, then where did it go?”

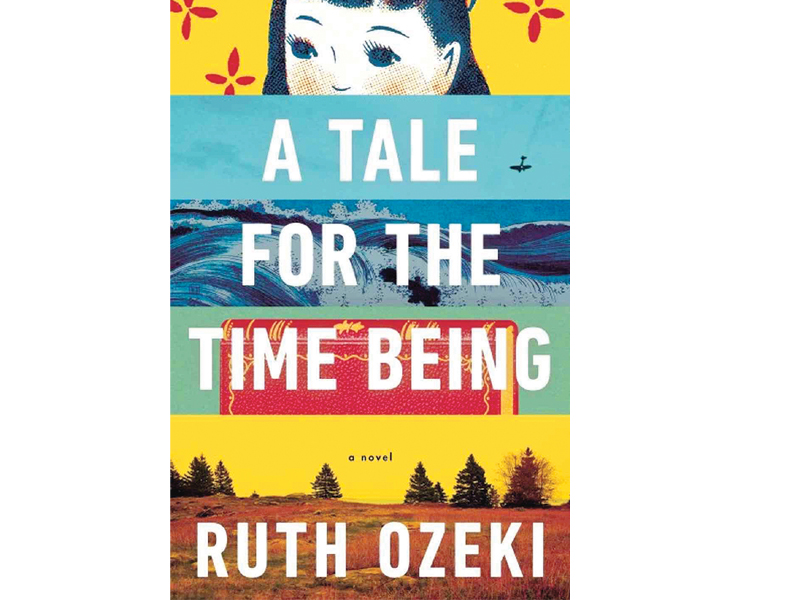

The above question comes from a 16-year-old Japanese girl, Nao Yasutani, who is suffering through the motions of teenage life in Japan in the ’90s. Nao is the restless yet unimaginably endearing daughter of a computer scientist who has to move back to Japan from Sunnyvale, California, following the dotcom crash and the loss of her father’s cushy job. The other protagonist of the book, Ruth, is an author who moves from New York to the backwaters of Canada, following her mother’s death. Her husband’s mysterious illness keeps her at the edge of peace, teetering between productivity and madness. Unable to tackle the manuscript of her pending autobiography, Ruth finds comfort in reading Nao’s tale, becoming more and more obsessed with the idea of finding and saving the young girl from her miserable life.

Ruth doesn’t really have an answer to Nao’s petulant questions. Ruth and Nao are not just spatially separated, they are also separated temporally. Their “conversation”, or rather Nao’s monologue, begins when Ruth discovers the young girl’s Japanese diary enclosed in a Hello Kitty lunchbox during a walk at the beach.

Within the pages of the crafty diary, Nao refers to herself as a “Time Being”. A time being, according to her, is simply someone who exists in time, and by that definition she brands everyone as a time being. The words prove prophetic in the span of the tale, which oscillates between Nao’s tragic attempts to come to terms with a life as a bullied outsider at her school. Furthermore, she has to deal with her father’s depression, failure to find work in an economically stilted Japan and various suicide attempts, and her mother’s cold brusqueness when she becomes the sole breadwinner in the family.

Echoing Murakami’s ambiguous and mercurial narrative shifts, A Tale for the Time Being gradually grips the reader by exploring the increasing isolation of young Japanese men and women within the garish new take on ‘culture’, bogged down by loneliness. On the other end of the spectrum, Ruth’s marital strain and creative lull slowly reveal a quiet disenchantment with her own Japanese heritage that is revived by her careful reading of Nao’s diary.

Ozeki, who is nominated for a Booker Prize for this book, masterfully weaves the story of a girl in a country not quite out of the past and suddenly thrust into the future. The fact that you can’t figure out whether Ruth is reading Nao’s story or Nao is writing Ruth’s will make you laugh, cry, become enraged and sad in one go. It will make you wonder, analyse and keep guessing about the welfare of the protagonists and the nature of ‘time’ till the very end, and even after that, as all good yarns must.

Japan on the pages

Japan, The Ambiguous, and Myself (1994)

This is the respected Japanese author Kenzaburo Oe’s 1994 Nobel Literature lecture. In a 46-minute speech, Oe recollected his hopes and fears as a young man growing up during the WWII in Japan, his spiritual affinity with American authors and living with the national regret of warmongering. It is available online as an audio recording and a transcript on the Nobel website.

Thousand Cranes (1952)

A complex and dark tale of love, betrayal, obsession and redemption set in post WWII Japan by the Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata. The book features an emotionally tortured protagonist who embarks on a torrid affair with his recently deceased father’s mistress and how his life’s focus shifts to her daughter when she commits suicide.

Woman on the Other Shore (2005)

Written by Mitsuyo Kakuta, Woman on the Other Shore is a tale of two women set in contemporary Japan, with one trying to overcome her present day woes, and the other battling demons from the past.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, October 27th, 2013.

COMMENTS (1)

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ