Urban heat island effect: Is Karachi heating up while the countryside keeps its cool?

Traffic, factories, air conditioners, buildings are all tweaking our city’s temperature.

Traffic, factories, air conditioners, buildings are all tweaking our city’s temperature. SOURCE: FARHAN ANWAR / DESIGN: JAMAL KHURSHID

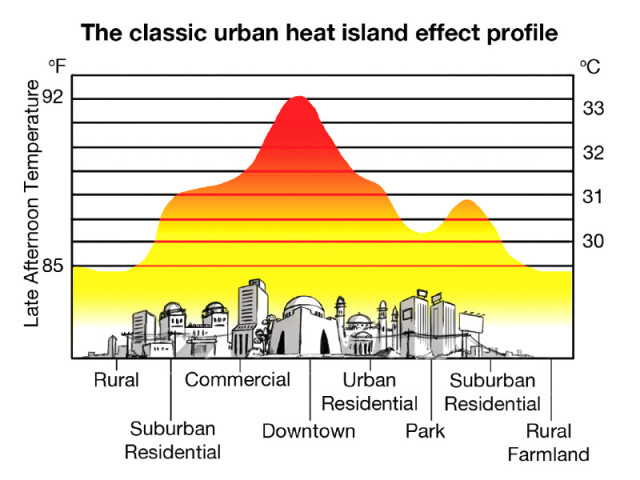

One likely scenario of climate change is the onset of extreme heat events with greater frequency. Urban settlements with specific land use and development profiles can generate unique conditions while interacting with heat events - the most significant being the Urban Heat Island Effect. This effect describes the warmth of urban surfaces and atmospheres in comparison to surrounding rural areas. Compared to rural areas, cities tend to have higher air and surface temperatures due to the urban heat island effect.

Heat generated by the movement of traffic, air conditioning systems, industrial emissions and other energy uses builds on the heat being radiated from buildings and roads, further raising temperatures. These are called man-made or anthropogenic contributions to the urban heat island effect.

In Karachi it is difficult to verify whether the urban heat island effect is taking place and if so, what is its intensity. Surface temperature mapping is the best way to go about it. Karachi could develop a typical temperature profile in which temperatures rise from the rural hinterland towards the city centre. However, available data on land surface temperatures in Karachi is inconclusive as it is random and not geared to measuring any urban heat island effect.

What is clearly evident, however, is the city’s residents and businesses are likely to be contributing to the need to reach for the AC switch.

There is a strong link between the density of development (eg population per square kilometre) and intensity of the urban heat island effect. Put more people in your drawing room for a party and you’ll need more air-conditioning. According to the Karachi Strategic Development Plan 2020, Karachi’s population is expected to hit 27.5 million by 2020. Population density within the core of the city is also on the rise.

The load of automobiles on our roads, particularly private vehicles, is going up. From 1990 to 2008, the number of vehicles added to our roads was greater than our population growth. According to the findings of a recent research published in the African Journal of Biotechnology (2010), there were 1,113,000 registered vehicles in Karachi in 2002 and 8,420,000 registered vehicles in 2007.

The numbers are likely to multiply. In a JICA demand forecast study - Special Assistance for Project Formation for Karachi Circular Railway Project, 2009 - vehicle ownership in 2020 was estimated at 61.6%. The population-to-vehicle ratio came out to 156 vehicles per 1,000 people. The emission of air pollutants is directly related to fuel consumption.

Add to this significant industrial development from 1947 to 1969 and during the years 1986 to 2009. The growth in industrial units compared to industrial areas to house them indicates that industrial zones became denser with time in Karachi.

What is important for city planners and managers is to improve their ‘understanding’ of urban development trends in overheating and associated risks. Only then can they plan to mitigate the impact by, for example, agreeing to increase the city’s ‘green cover’ or implementing a transport policy that discourages the use of private vehicles and focuses on promoting sustainable public transport. Few would argue that we need to also focus on alternative and environment-friendly energy sources to reduce pollution in our air.

Farhan Anwar is an urban planner and runs a non-profit organization based in Karachi city focusing on urban sustainability issues. He can be reached at fanwar@sustainableinitiatives.org.pk

What is the Urban Heat Island Effect?

The fabric of buildings and roads that make up our city absorb solar energy. By early evening, the buildings and roads start to radiate this stored energy as heat, which escapes slowly, especially in narrow or tall streets where it is re-absorbed and re- radiated from the buildings that line the street. This absorption and retention of heat is why urban areas can be warmer at night than rural areas. This is known as the ‘urban heat island effect’

Published in The Express Tribune, August 26th, 2013.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ