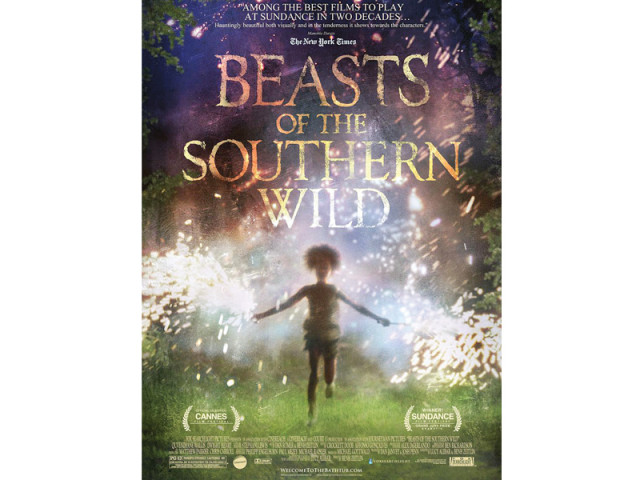

Movie review: Beasts of the Southern Wild - down on the bayou

The movie has been dubbed fantasy drama, although the literary genre known as magic realism seems more apt.

While the voiceovers are, at times, a little difficult to understand, we gather that she has a father named Wink who is clearly a flawed man — short-tempered, impatient, and apparently has a heart condition or some medical problem. Yet, as abusive as he can be, he still loves Hushpuppy and in his own way has found his niche in this milieu.

The first adult female we see gives Hushpuppy and other children a lecture about the reality of the natural world and its beastly imperative to eat or be eaten. We’re all meat, she informs them, which reminds me of the Woody Allen quip that nature is essentially one big lunch buffet. The kids learn about global warming and the melting of the polar ice caps, flooding coastlines, especially the swamps which they inhabit. The big event early on in the plot is an impending storm, confronting the residents with a choice to stay in Bathtub or flee, with most taking the safer option. The rest of the movie basically concerns itself with the storm’s aftermath, the survival of those who stayed put, and an eventual intervention by outsiders.

The movie’s central themes — our dependence on nature and on each other, nostalgia for a way of life where we knew our place in the world, resilience, threats to the environment from our modern lifestyle and technology, the value of giving and forgiving — are exemplified best by Hushpuppy’s wisdom, by also by its inter- and intra-community dynamics.

The first thing one notices is that while the film shows what is, in many respects, typical depictions of poor Americana, it’s one many of us seem to have forgotten still exists. These are not urban black youth living in a ghetto, blasting hip hop on their stereos, driving flashy cars, or playing basketball on blacktop in a concrete jungle, but a people who, despite being surrounded by the city and its intrusions, live organically (if that word is even in their vocabulary). This is not to say that the film is free of stereotypical characters found in older American lore, but it is good to remind us that many poor communities are still rural, and often remain invisible to modern pop culture. Bathtub is not strictly an African American community, as white and black live together seamlessly, with no hint of their racial otherness. They’re all equal here, equally poor.

The movie has been dubbed fantasy drama, although the literary genre known as magic realism seems more apt. At points its cinematography gives it a documentary feel, at other times perspectival and subjective in an almost Terrence Malick-esque style. The film has a pathos running through it that tempers any off-putting cleverness that its quick cuts, eccentric shots, and dialogue could engender in mainstream audiences. Zeitlin’s debut is quite impressive, and there is buzz that it’s an Oscar contender. Given a largely non-professional cast and crew, it’s hard to say whether that makes the high-quality performances all the more impressive, or just what Zeitlin was aiming for in his use of locals to depict locals.

Tall-tales, poetic license, and idiom — the primordial heart of all mythology — stands as an almost lost art, amongst the “reality” shows, suburban sprawl, and technocratic uniformity of 21st century America. The charm of southern wit and old-fashioned story-telling, so well-captured in Big Fish, is more subtlely employed here, to good effect. With irreverent and kitschy internet memes like Chuck Norris, it’s important to remember that we once had folk heroes like John Henry.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, December 23rd, 2012.

Like Express Tribune Magazine on Facebook and follow at @ETribuneMag

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ