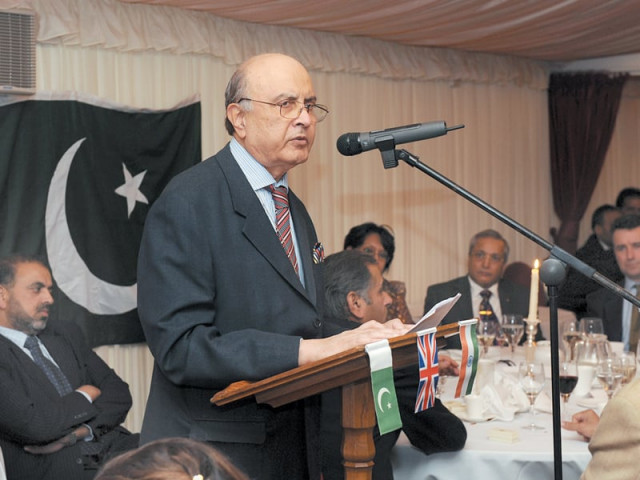

The lord from Lucknow

Honoured by Pakistan, India, London-based Baron Khalid Hameed works quietly to heal sick, promote inter-faith harmony.

But when those two countries are Pakistan and India, then the number of people so honoured could probably be counted on the fingers of one hand. Well, Baron Khalid Hameed of Hampstead is one such person, being the recipient of India’s Padma Bhushan, as well as Pakistan’s Sitara-e-Quaid-i-Azam and Hilal-e-Quaid-i-Azam.

We are meeting in his office in London’s Harley Street, which is world famous for being at the forefront of medical science and for attracting pioneering medical specialists from all over the world.

He’s not out of place in the caduceus crowd either. Trained as a doctor in his hometown of Lucknow, 71-year-old Hameed is the chairman of the Alpha Hospital Group and CEO of the London International Hospital. Previously, he was also the executive director of London’s Cromwell hospital, famous for treating affluent Middle Easterners, the likes of former Manchester United footballer George Best and the Iron Lady, former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, herself.

As I introduce myself to him, I keep wondering why so few people know about him. There is practically no mention of him in the Pakistani press, even though he’s essentially doing the same job as Lord Nazir Ahmed. “I’m a professional you see,” responds Hameed. “I don’t like wasting too much time on these things because what tends to happen is that the task at hand often gets delayed,” he says in an extremely measured tone, choosing his words carefully.

In February 2007, Hameed was made a non-party political life peer, giving him a seat in the House of Lords, and in 2009, he received the Padma Bhushan, one of India’s highest civil award for his services to the medical profession. He has also received the Sitara-e-Quaid-i-Azam and the Hilal-e-Quaid-i-Azam for his services to medicine in Pakistan.

But he’s not interested in talking about these awards or the more recent ‘Freedom of the City of London’ award he received. Instead, he wants to stick to what is obviously his cause celebre: promoting inter-faith understanding in his role as the chair at the Woolf Institute of Abrahamic faiths.

“My interest in the field developed after 9/11 when Islam was being painted as a religion for brutes and uncivilised people who do not know how to live in the modern world,” says Hameed.

“And at that time, I was looking for somebody to come forward, take responsibility and stand up and say Islam is a religion of peace. Nobody did.”

Of course, that didn’t stop Hameed from standing up and saying his piece. “The Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) himself had very good relations with non-Muslim tribes living in his area. There is an incident in which he stood up in respect as a Jewish man’s funeral was passing by, and later when people asked him if he knew the man was Jewish, he replied: ‘Of course!’” says Hameed.

As the conversation continues, I realise it isn’t just Islam that he talks about with utmost respect and positivity, but all Abrahamic faiths. I then make the mistake of saying as much.

“You shouldn’t just talk about ‘Abrahamic’ religions because there are one billion Hindus in the world,” he says as he gently rebukes me. “You can try and ignore them but they still exist. Similarly, Sikhs are formidable in terms of influence, so you have to include all of the other religions in this discussion too. The more I read other scriptures, the more I realise what excellent books they are, as all of them tell you to be kind, to help those who are in need and to be good citizens. Not a single religion teaches us to be negative or destructive; they are all different channels of water merging into the same sea,” he says with sage-like wisdom.

I try to steer the conversation away from my faux pas and back to his topic of choice: What exactly does working for inter-faith harmony entail? I ask. And in particular, what does it mean Muslims should be doing?

“[It means] we don’t need to be swept away by emotion,” he says. “It doesn’t mean that you should convert to my religion or that I should convert to yours. Instead, we should discuss and at least agree on some things. The more you talk, the more you realise that there are more similarities than differences between us.”

Sadly, Hameed feels that the Muslim community in the UK is becoming increasingly isolated and ghettoised. But if that’s something he finds worrying, how then does he view the radicalisation and ‘religious’ violence taking place back in Pakistan?

“These people say that they are doing God’s work but the Quran clearly prohibits killing another human being. And as Muslims, all of us believe in an afterlife so why don’t we leave it for God to decide? What’s the hurry? And if they don’t agree [with this] they should tell us that the Quran is not true,” he argues.

He believes that Muslims and non-Muslims alike misconstrue the word ‘jihad’. “The word literally means ‘to strive’ and the greater jihad is to improve oneself and the secondary and lesser jihad is to defend yourself when you’re attacked. These days most Muslims seem to forget the primary meaning and instead just focus on the auxiliary meaning,” he says.

Other than trying to foster goodwill in a multicultural city, his passion is helping young people fulfil their potential, which is why he chairs the Commonwealth Youth Exchange Council and is the governor of the International Students House.

“The young people of today are the guardians of our civilisations, but Muslim youngsters in particular are at the bottom of the league in comparison to the rest of the country. They have the highest numbers in prisons and they have the worst health profile,” he says.

He is at pains to point out that Indians are doing better than Pakistanis in the UK. He refers to a survey done in Yorkshire, which claims that the majority of Muslims and Pakistanis aim to become taxi drivers so that they can start earning some quick cash. “Not that there is anything bad in being a taxi driver, but [they want] nothing more than to be a taxi driver,” he says.

When I ask him how this situation can ever change, he replies: “The goal should be to create an educated generation and the change will have to come from the home and the parents.”

He blames himself and me, the people upon whom God has bestowed all the luxuries of life, who own motor cars, have wardrobes full of clothes, eat (at least) three square meals a day and are yet too ‘busy’ to contribute to the community.

“It is well-to-do Muslims like you and me who need to build academic institutions like medical and engineering colleges and not just mosques, because that is what will benefit the community in the long run.”

I ask him if the goal seems achievable, and he replies with his customary passion: “Very much so. People are willing to embrace you if you prove your mettle. When I first came here, I wanted to get ahead and so I worked over 50 hours a week. I had no time for Sunday biryanis or anything like that. First, you have to work hard and then you can seek blessings from God.”

This affable and refined man who despises extremists seems to have a view on everything, so I ask him what he thinks of his birth country’s next door neighbour: Pakistan.

“I’ve been to Pakistan several times to attend weddings and I have a lot of friends there. One of the things I’d still like to achieve is to open a hospital in both Karachi and Lucknow.”

I wonder out loud if he plans to start something like Imran Khan’s Shaukat Khanum Memorial Hospital, but he clarifies that he doesn’t want to open a specialist hospital but rather a general hospital that can cater to the poor populations of Pakistan and India.

Still, with a peership, the inter-faith harmony project and the stewardship of no less than two hospitals, how on earth will he find the time and energy to devote to this project?

As if reading my mind, he recites a couplet that sums up his philosophy of life and the secret of his success:

Khuda taufeeq deta hai jinhain, samajhtey hain woh

Khud hi apne hathon se buna karti hain taqdeeren

Correction: The story erroneously called Padma Bhushan the highest civil award in India. It is, in fact, one of the highest. A correction has been made. We regret the error.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, September 23rd, 2012.

Like Express Tribune Magazine on Facebook and follow at @ETribuneMag

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ