Golden jubilee: From sleepy town to vibrant city, Islamabad turns 50

Half-a-century after officially opening for business, Islamabad’s water, infrastructure problems linger.

On a warm Monday morning, the head of the recently created Capital Development Authority (CDA), WA Shaikh, announced at a press conference in 1962 that the nation’s new and planned capital city, Islamabad, has come into being and ready to function.

During the half century since June 4, 1962, the little patch next to the Margalla Hills, populated only around the shrine of Bari Imam and a few scattered villages, became a sleepy little town joked about being half the size of America’s Arlington Cemetery and twice as dead, into a legitimate metropolis of almost 1.8 million.

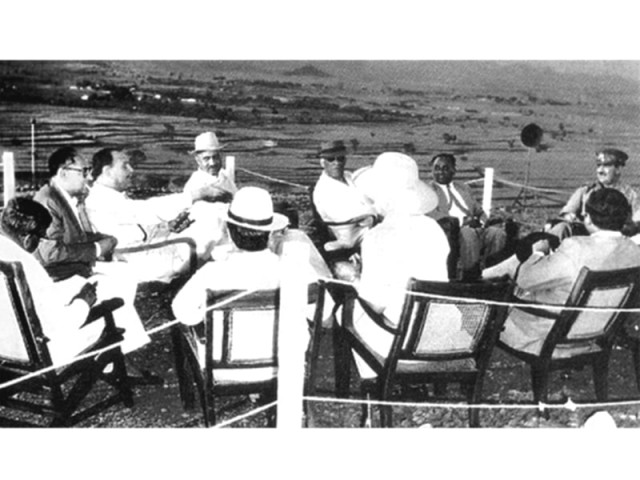

The green hills of Shakarparian, from where General Ayub Khan gazed over the empty patch, has become a popular recreation spot, albeit one that is now under threat of commercial activities and environmental degradation posed by an FWO asphalt plant, with trees to be replaced by steel structures that will form a cricket stadium.

There are too many anecdotes about the city to run through, although one memorable reflection of the yes men that surrounded Gen Khan is worth telling. When the military dictator sought suggestions for the nascent city’s name, a now deceased member of his staff once recounted the rejected suggestions that included Islampur, Muslimabad, and of course, Ayubabad. Thankfully, even the dictator found the last one to be a little over the top.

The idea of Islamabad was not one that came up overnight. The location of the old capital, Karachi, vis-à-vis the map of West Pakistan made it difficult to access from the rest of the country. In addition, the proximity of Karachi to the Arabian Sea made it very vulnerable to a naval assault. Finally, the location selected for the new capital was closer to army headquarters in Rawalpindi and the disputed territory of Kashmir in the north, issues that were not lost on the military ruler.

In 1958, a commission was constituted to select a suitable site for the then unnamed capital, which then hired Greek architect Konstantinos Apostolos Doxiadis to design a master plan for the city, eventually one based on a triangular grid plan, with its north facing the Margalla Hills. The long-term plan was for Islamabad to eventually encompass Rawalpindi; stretching to the west of the historic Grand Trunk Road on the Pothohar Plateau, considered to be one of the earliest sites of human settlement in South Asia and one that could reflect the diversity of the Pakistani nation.

Another aspect of the broader plan for Islamabad was to make it an ‘international city’, something that never transpired due to rising extremism in the country and particularly the penetration of vigilante right-wingers in the city.

The capital was not moved directly from Karachi to Islamabad, as the absence of structures like markets and housing made it unviable until 1966, when bureaucrats started populating the city. The garrison city, Rawalpindi, was made the temporary capital, with most offices housed around the old Presidency, now Fatima Jinnah Women University, at Kacheri Chowk.

Sadly, after the shift of the seat of government to Islamabad, Doxiadis plan was never fully adhered to.

Although “the master plan is not sacrosanct” in the words of former CDA chief and current CADD Secretary Imtiaz Inayat Elahi, without amending CDA bylaws, anything against it is illegal. Evidence shows that this only applies in theory.

Today, people still face water shortages, while the lack of a proper sewerage system has turned the once pristine streams into stinking black drains. Pollution is not restricted to the water, as reckless cutting of trees has marred the city’s green look, while polluting industrial units, once concentrated on its outskirts, illegally moved in close to the heart of the city and were retroactively legalised, a process now most visible with large home-based offices.

Although a public bus transport plan for the city is in the works, as it has been for almost two decades, it would come about 30 years too late.

Meanwhile, the original roadmap, chockfull of underpasses and overpasses and without a streetlight in the city, was replaced by one where even the highways have no less than three.

The entertainment front fares little better, as the city’s only cinema was torched by religious extremists of a few years back. Only one international-level sports facility exists in the city, and even that needed major upgrades to host the South Asian Games.

In addition, political apathy and bureaucratic red tape have left almost 300,000 people in 52 settled areas straddling the Islamabad-Rawalpindi boundary without any civic amenities. This is because when the territorial boundaries for the twin cities were settled in the 1980’s, the revenue limits never were. Now, vested interested are delaying any action to ensure these areas are demarcated in Islamabad to ensure higher land values.

When Sheikh Mujeebur Rehman, the founder of Bangladesh first visited the site of Islamabad, he remarked, “I smell the jute fields of Chittagong,” referring to the fact that while development in East Pakistan was limited, extravagant amounts were to be spent on the new capital. Today, that same complaint legitimately echoes from many quarters of modern Pakistan, especially Balochistan. Hopefully, Islamabad will continue to develop, but not at the cost of the rest of Pakistan.

Published in The Express Tribune, June 5th, 2012.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ