Teachers are responsible for turning children away from schools: Taj Haider

At opening at Dadu law college, criticism heaped on the education system.

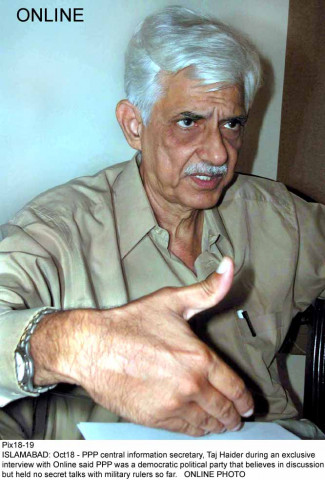

Mr Minister, can you give me back that school of thatched straw where teachers helped inculcate the thirst of knowledge in my soul, asked Taj Haider, the Pakistan Peoples Party’s secretary general in Sindh, during a fiery speech on Saturday.

He spoke at a seminar on ‘Education for All and Dropout Rate in Remote Areas’ at the newly built Pir Illahi Bux Government Law College located in the heart of Dadu, which on the day was baking as the mercury climbed to 44 degrees Celsius.

The seminar developed momentum only when Haider, the third last speaker, took to the podium and stole the show with his speech. He spared no one to highlight the gravity of the situation and the futility of efforts being put into resolving the education crisis.

For Haider, reality was far from official statistics brought up by other speakers. For him, children are uninterested because they don’t actually learn anything in the current system. “This rote-learning system under the supervision of unqualified teachers is only making them more illiterate,” he said.

Today headmasters are paid more than parliamentarians yet they fail to make a difference. It is no secret that more than half of government teachers do not even show up at schools to fulfil their 156-day duty during a year.

“I’m saying this with full responsibility that our teachers are the main hurdle in the improvement of our education system despite all the monetary input,” said Haider, quipping that at a time when elections are near, he cannot afford to aggravate the sentiments of teachers, who will be posted to polling stations.

While pointing out that a gun culture disturbs work at 130 public colleges in Karachi, the PPP leader said that if such colleges are to be opened in rural Sindh, it is better to donate that money to charity. “First, we need to improve on what we already possess and only then will we be able to move forward,” he asserted.

The solution rests in the mobilisation of civil society and the ultimate beneficiaries, who should know that it is their money paid through taxes which the government is spending on education. “Otherwise, investment worth billions will go to waste like in the past and termites will infest the textbooks stuffed in storerooms,” he added.

Haider started off with a brief recollection of his conversation with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto some 45 years ago, during which ZAB had resolved that it would only require 10 to 12 years of untiring efforts to educate the entire nation. “But during the last 45 years, the situation has only improved slightly,” he said “It is us who have to see where exactly we have erred.”

It was ironic that as Taj Haider spoke of improving existing schools, Education and Literacy Minister Pir Mazharul Haq, who presided over the seminar and belongs to the same party as Haider, announced that 23 new colleges will be set up in Sindh. They will have hostels for women lecturers, he announced.

The education department will announce vacancies at colleges from now on and the applicants will not be transferred to any other college according to their wishes, he added.

On the school dropout rate, Haq plans to upgrade around 1,100 primary schools to the elementary level. “In contrast to more than 44,000 primary schools, at present we only have some 4,000 middle and secondary schools,” he said. “More than 6,000 high schools are needed to accommodate the 3.2 million children enrolled at primary schools.”

“Whatever reforms we tried to make were from an education budget which is merely 1.24% of our GDP,” he added.

During the seminar the minister seemed to be vexed by the few ‘solutions’ presented by Haider, Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi’s Dr Baila Raza Jamil and Unicef Sindh chief field officer Andro Shilakadze.

According to Jamil, 29% of children aged between 5 and 16, who are not enrolled at schools, have become more of a challenge for Sindh than the primary dropout rate, which is 25 per cent. The attendance rate in these schools is a mere 62%.

“The system needs a major overhaul, including the quality of teachers at these schools,” said Jamil.

The total enrolment of students in Class I is around 3.2 million but it declines to merely 0.9 million when the students reach Class V, she added.

Along the same lines, Unicef’s Shilakadze also challenged the audience with his question: “Why does a man living in rural areas not want his children to go to school – it is for you to find out?”

He said that during the recent floods, the Unicef facilitated around 100,000 children at its shelter schools, where 40% of students had never been to school before. “But what I know is that they were happy being in school and were eager to learn.”

Published in The Express Tribune, May 30th, 2012.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ