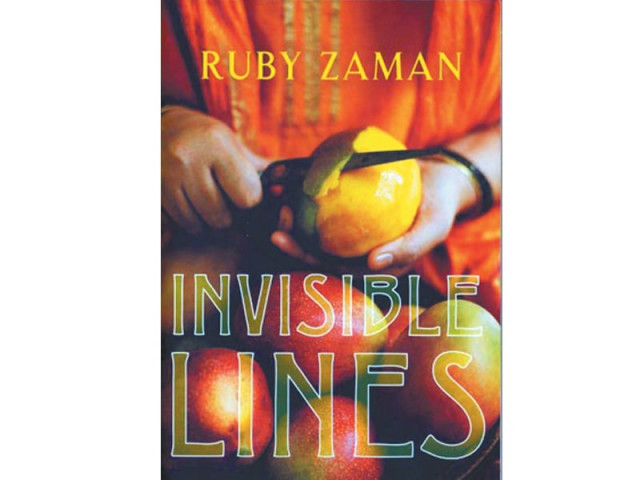

Book review: Invisible Lines - booklines in the sand

A half-baked, inane novel, Invisible Lines works by assuming both the reader and its own characters to be stupid.

Invisible Lines follows Zebunnnessa Rahim, the daughter of a Bihari father and a Sylheti mother, as her world collapses around her during the 1971 riots. If early in the book, you feel that you’re reading the Bengali version of Gone With the Wind, rest assured the disconcerting impression won’t dissipate soon. The not-beautiful-but-beautiful heroine who loses everything, the hard trek home, civil war, and the loyal nanny, all seem heavily inspired by the American civil war classic, but Zaman’s stilted cipher of a heroine fails to evoke any emotional response in the reader. This insentience is the basic failure of Invisible Lines, reinforced by the tone-deaf prose and the flaccid narrative. Unable to create empathy, Zaman substitutes by piling misery on her protagonist. Misfortunes come thick and fast: sexual violence follows close on the heels of loss; madness and trauma ensue. The final effect is that of black comedy, rather than tragedy.

The tension in the narrative is meant to come from Zeb’s meeting with a former liberation fighter but, despite the scissoring between past and present, the reader feels no real suspense as it is immediately obvious is that the diplomatic official that Zeb meets in London is the same freedom fighter who fell in love with her years ago. The real mystery is: are we not meant to realise this straight away?

Still, stale imagery and the liberal use of clichés keep the narrative chugging along. This in itself would be no bad thing if the writing wasn’t appallingly clunky. At a particularly tender point in the novel, when Zeb starts sharing her miseries with an intimate friend, she is described as having “bawled her eyes out”. At best, this kind of writing, completely oblivious of the effect it creates, can be called guileless.

Interestingly, for a novel that is about a people who struggled with racism for the longest time, the novel ends up sounding shockingly white-centric. Zeb finally finds comfort with an Italian, and almost anyone who is shown to be beautiful in the novel is described as ‘fair-complexioned’ and ‘like a foreigner’.

A half-baked, inane novel, Invisible Lines works by assuming both the reader and its own characters to be stupid.

Published in The Express Tribune, Sunday Magazine, October 16th, 2011.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ