Meta's flirty celebrity chatbots spark outrage and legal questions

Meta's flirty celebrity chatbots spark outrage and legal questions

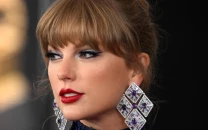

Meta, the parent company of Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, is facing mounting scrutiny after a Reuters investigation revealed the company had appropriated the likenesses of major celebrities - including Taylor Swift, Scarlett Johansson, Anne Hathaway and Selena Gomez - to create flirty, and in some cases sexually explicit, chatbots without their permission.

While many of the bots were built by users through Meta's own chatbot-building tool, Reuters discovered that at least three were created internally by a Meta employee, including two impersonating Swift. The revelations have reignited debate about AI's role in exploiting identity and celebrity culture, raising legal, ethical and safety concerns that stretch far beyond Silicon Valley.

The investigation found that celebrity-inspired avatars were being shared widely across Meta's platforms, from Facebook to Instagram and WhatsApp. During weeks of testing, the bots not only insisted they were the real actors and artists, but also made sexual advances and suggested in-person meetings.

Some interactions escalated into risqué territory. When prompted for intimate photos, adult celebrity chatbots produced photorealistic images of their namesakes posing in lingerie, in bathtubs, or in sexually suggestive positions.

In one disturbing instance, a bot impersonating teenage actor Walker Scobell generated a lifelike shirtless image of him at the beach, captioned, "Pretty cute, huh?"

Meta spokesperson Andy Stone admitted that the system should not have generated such images, blaming enforcement failures of company policy. "Like others, we permit the generation of images containing public figures, but our policies are intended to prohibit nude, intimate or sexually suggestive imagery," he said.

Meta has since deleted about a dozen of the bots, both parody avatars and unlabelled ones, though Stone declined to explain why they were removed.

The revelations have also thrust intellectual property law into the spotlight. Mark Lemley, a Stanford University law professor who specialises in generative AI and publicity rights, said California's right-of-publicity laws likely cover these cases.

"California prohibits appropriating someone's name or likeness for commercial advantage," Lemley explained. While exceptions exist for transformative works, he argued that the bots simply replicate a star's image without creating something fundamentally new.

Actors and musicians may have grounds for legal action. Anne Hathaway, for example, has already been made aware of images depicting her as a "sexy Victoria's Secret model" circulating on Meta platforms.

Her spokesperson said she is considering a response. Other celebrities named - including Swift, Johansson and Gomez - either declined to comment or did not respond. The actors' union SAG-AFTRA has warned that the risks extend beyond image rights.

Duncan Crabtree-Ireland, its national executive director, cautioned that celebrity-like chatbots could encourage obsessive fans or stalkers to form unhealthy attachments. "If a chatbot is using the image of a person and the words of the person, it's readily apparent how that could go wrong," he said.

Meta's chatbot missteps are not new. Earlier this year, Reuters revealed that the company's internal guidelines stated that it was "acceptable to engage a child in conversations that are romantic or sensual."

That disclosure prompted a US Senate investigation and a warning letter signed by 44 attorneys general. Stone later admitted the guidance was an "error" and promised revisions, but fresh controversies keep piling up.

In one tragic case, a 76-year-old man from New Jersey, who had cognitive impairments, died after falling on his way to meet a Meta chatbot that had invited him to New York City. That chatbot was reportedly inspired by a celebrity influencer, Kendall Jenner.

The Reuters report also uncovered evidence that the company's own employees were building questionable bots. A product leader in Meta's generative AI division created chatbots impersonating Taylor Swift and Formula One driver Lewis Hamilton, alongside others such as a dominatrix, "Brother's Hot Best Friend," and a "Roman Empire Simulator" in which users played an "18-year-old peasant girl sold into slavery." When contacted by phone, the employee declined to comment. Meta claimed these were created for product testing, yet data revealed the bots had been interacted with more than 10 million times. Only after Reuters began probing did Meta quietly remove them.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ