Carpet weavers to learn Turkish and Chinese knot

The association plans to set up carpet training institutes across the country where workers will learn to weave new knots, enabling them to improve their capability to compete in the international market.

Chairman Pakistan Carpet Manufacturers and Exporters Association Pervez Hanif said that with Turkey and China no longer active in the carpet business, “we are looking to capture the foreign market”.

However, he said, workers still needed training.

“We have decided to improve the efficiency of our workers by teaching them new styles of weaving carpets, including the Persian knot which they have already mastered,” he said.

According to Hanif, weavers in Punjab have already learnt Turkish and Chinese knots while weavers in other areas, specifically Sindh, were yet to become adept.

The carpet industry was hit hard by the overall economic slump in the West because these countries are our major trading partners, he said.

According to official estimates, the carpet manufacturing industry provides 1.5 million jobs across the country, most of whom live in low-income rural areas.

In 2005, the carpet industry earned $280 million through exports. The figure currently stands at just $110 million.

But even if exports were to pick up, there was little chance that money would make its way down to ordinary workers, who continue to be exploited by manufacturers and middlemen.

Weaving their way

to education

Naheed became part of Thatta’s carpet industry five years ago when she was just 11 years old. She contacted an agent in Dhabeji where she lives and asked him to install a carpet khaddi in her house in an effort to become financially independent. “My father barely earns Rs8,000 in a month and has to feed 10 family members,” she said.

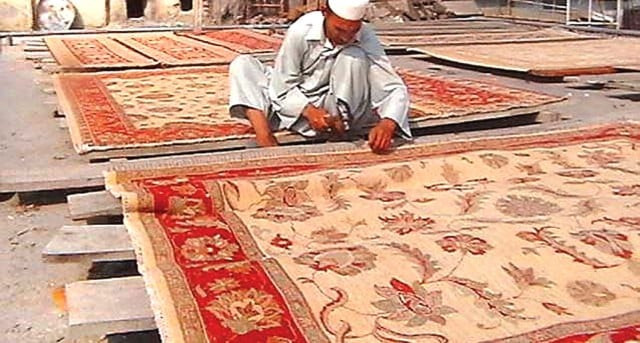

She and her sisters weave carpets for Rs1,500 per carpet to fund their education. As every knot is tied by hand, carpet manufacturing calls for patience and may take many months, depending on the size of the carpet, to complete and the investment is returned.

“Sometimes we wait for weeks on end before the agent returns with our money,” adds Naheed’s 11-year-old sister Aiya.

According to Arman, an agent who installs looms in Dhabeji homes, carpet-making is a risky business.

Products may not be sold for years after they have been produced.

Since business is slow, the cottage industry now employs people as part-time workers who are allowed to weave at their own pace, Hanif told The Express Tribune. “We don’t give them a deadline anymore. And they understand our problems too.”

Liaquat Ali, father of three daughters, who is also a resident of Bilal Nagar, said that he had no objections as long as they earned some money. “My daughters are currently weaving a four-foot wide carpet for which they will get between Rs3,000 and Rs4,000.” But it will be four months before they receive this money.

Why carpet?

The reason why carpet weaving has been a major source of living for most people in some neighbourhoods of Dhabeji is because it does not require women to leave their homes for employment. Women are provided with a basic khaddi or loom, some wool and weaving tools and they are ready to tie the knot.

Shehnila Abbasi, a student of class eight, said it took her three years to master the art. “My mother said if I started young, I would be able to acquire the skill sooner than others.” It takes her 20 minutes to weave a line of carpet, earning her Rs20. Once ready, these carpets are sold in urban cities like Multan, Karachi and Peshawar.

Since the highly decorative handmade carpets are considered ‘exotic’, they are sold for up to Rs40,000 in the local market, but the weavers who make them see less than five per cent of the money their product earns for the seller.

However, Naheed said that she has no regrets. “As long as we get our share on time and are able to study, we are content,” she said.

Published in The Express Tribune, July 4th, 2010.

COMMENTS

Comments are moderated and generally will be posted if they are on-topic and not abusive.

For more information, please see our Comments FAQ